From the Editors

In October 2015, in the first issue of Guftugu, we described what we were up against:

If singing and dancing, poetry and prose, film and painting have all been possible even in the most brutal times history has witnessed, we can believe our situation today too cannot subdue what we can do with artistic practice of all sorts, as well as education. Every day we see new evidence of authoritarianism in India – the sort of tyranny that impinges on our cultural work, and on those who wish to partake of what we imagine for them. Even the day-to-day cultural practices by the wide range of people who make up India are vulnerable to the aggression of the “cultural police” in different guises. These policemen want to tell us all what to eat, wear, read, speak, pray, think. They want to tell us how to live.

We made a promise to fight this:

Guftugu aims to reflect and critique present-day aggression against culture; to articulate creative resistance against the degeneration of democratic values and institutions; and to achieve this by freely doing what we do best: writing, painting, imagining, speculating and debating.

The challenge has grown since then.

The question confronting us every day, in the classroom, the courts, on the streets, and even in our neighbourhoods and homes, is this: How do we grow our resistance everyday? How do we learn to hear, understand, and amplify, in solidarity, in word, image and gesture, the voices of all the people, young and old, in every nook and corner of the country, who are subject to discrimination, fear, hatred, poverty?

In other words: What kind of India do we want?

This is the kind of India our cultural community have asked for through Guftugu:

- A country bent on annihilating caste.

- A country where diverse communities mingle and thrive.

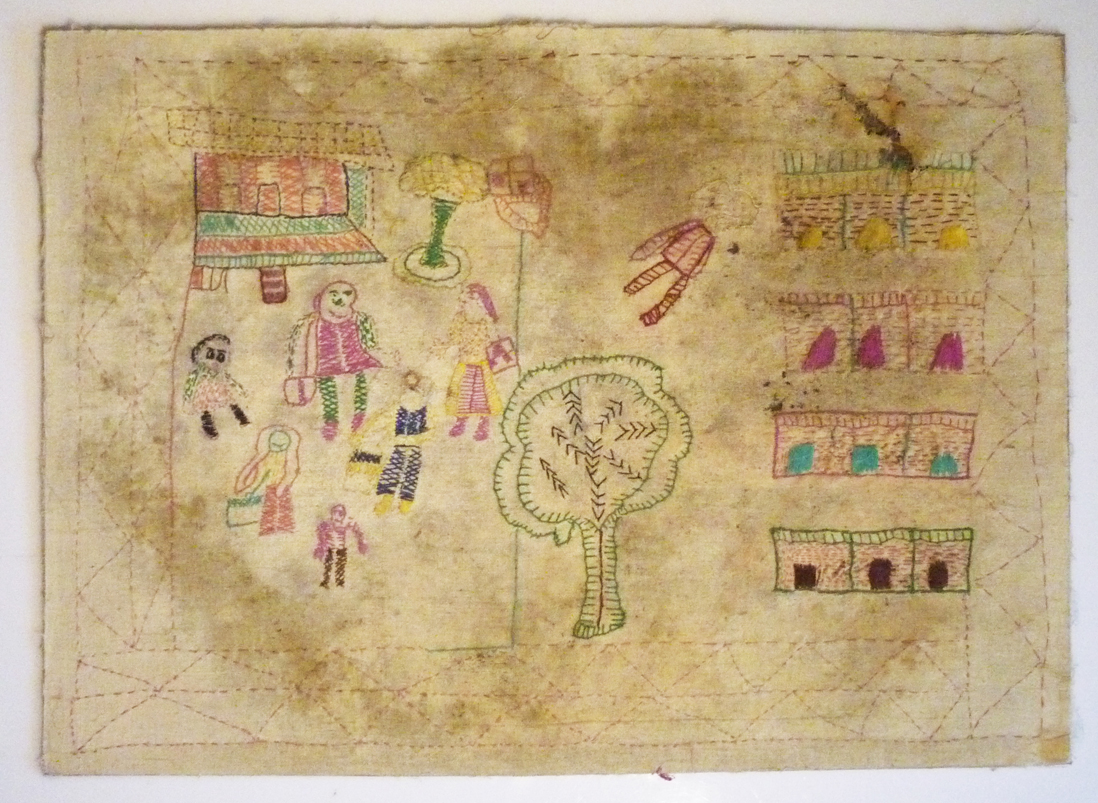

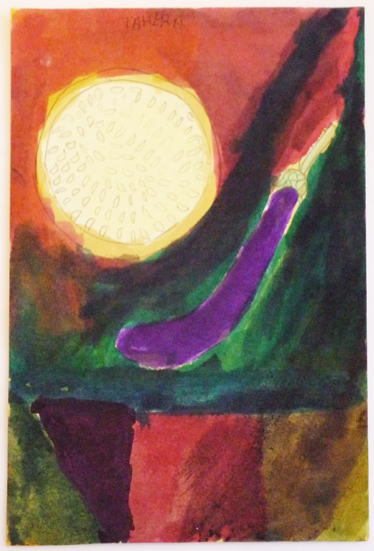

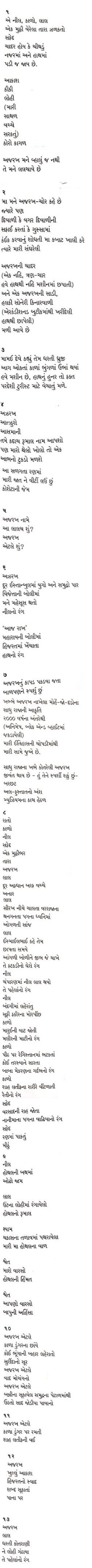

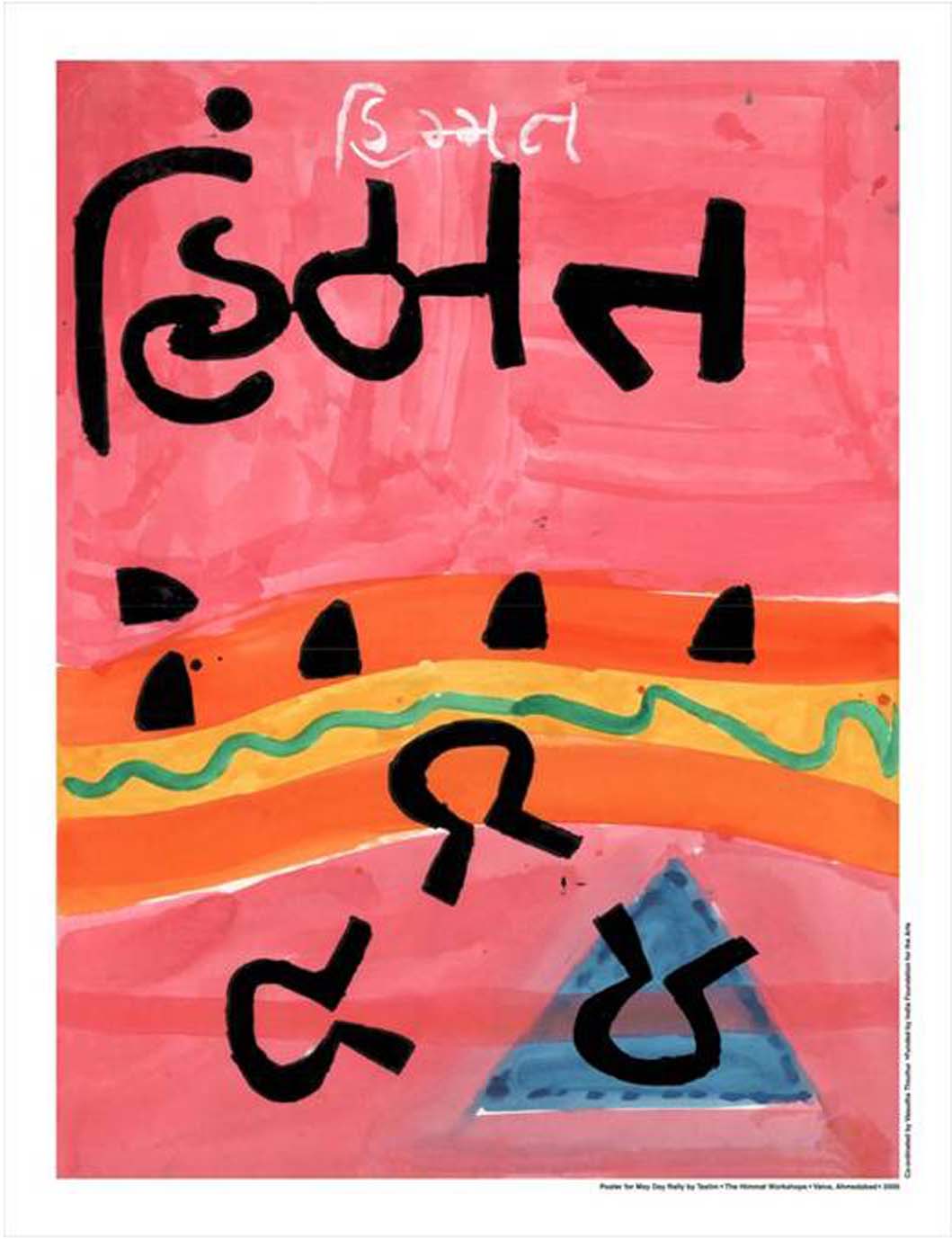

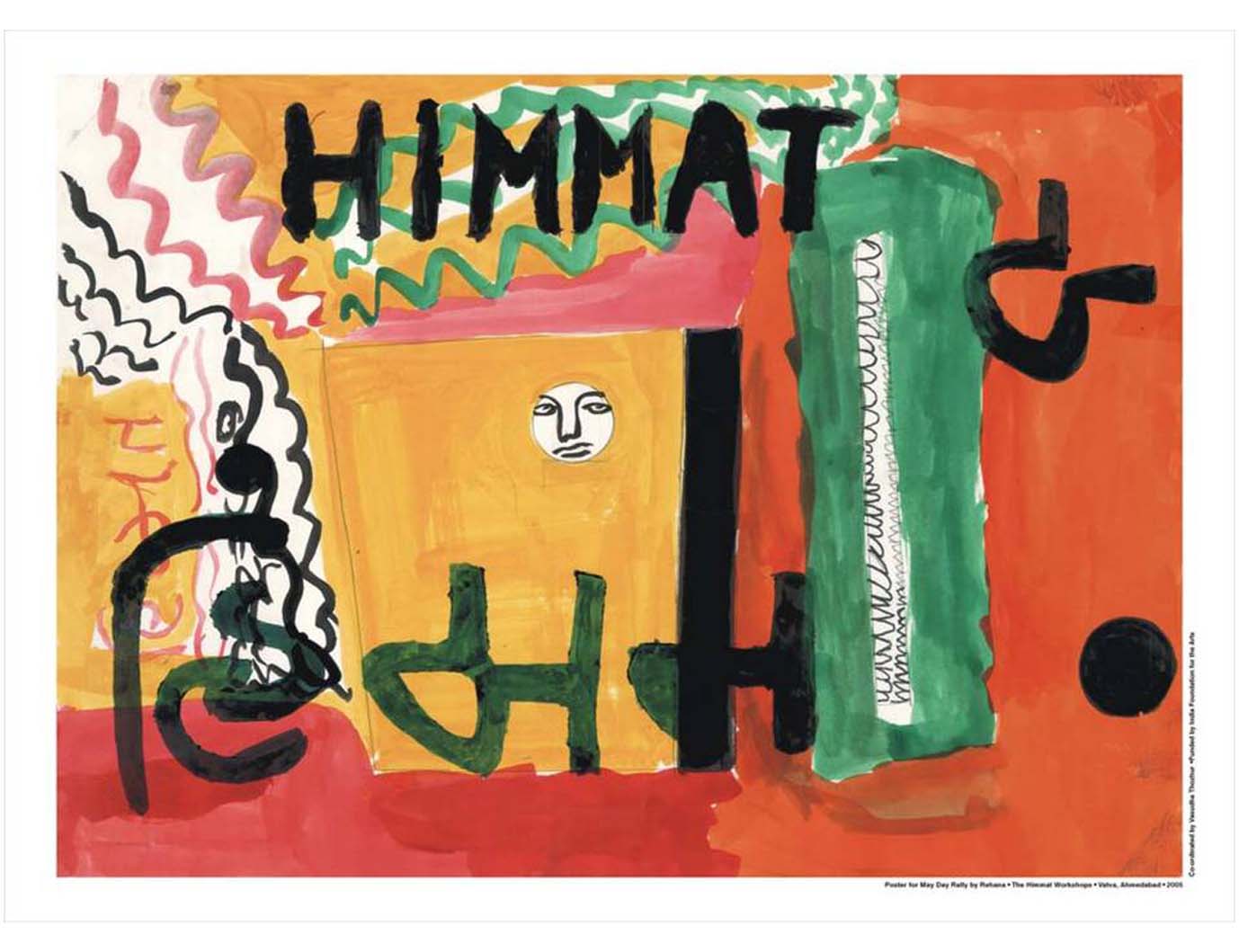

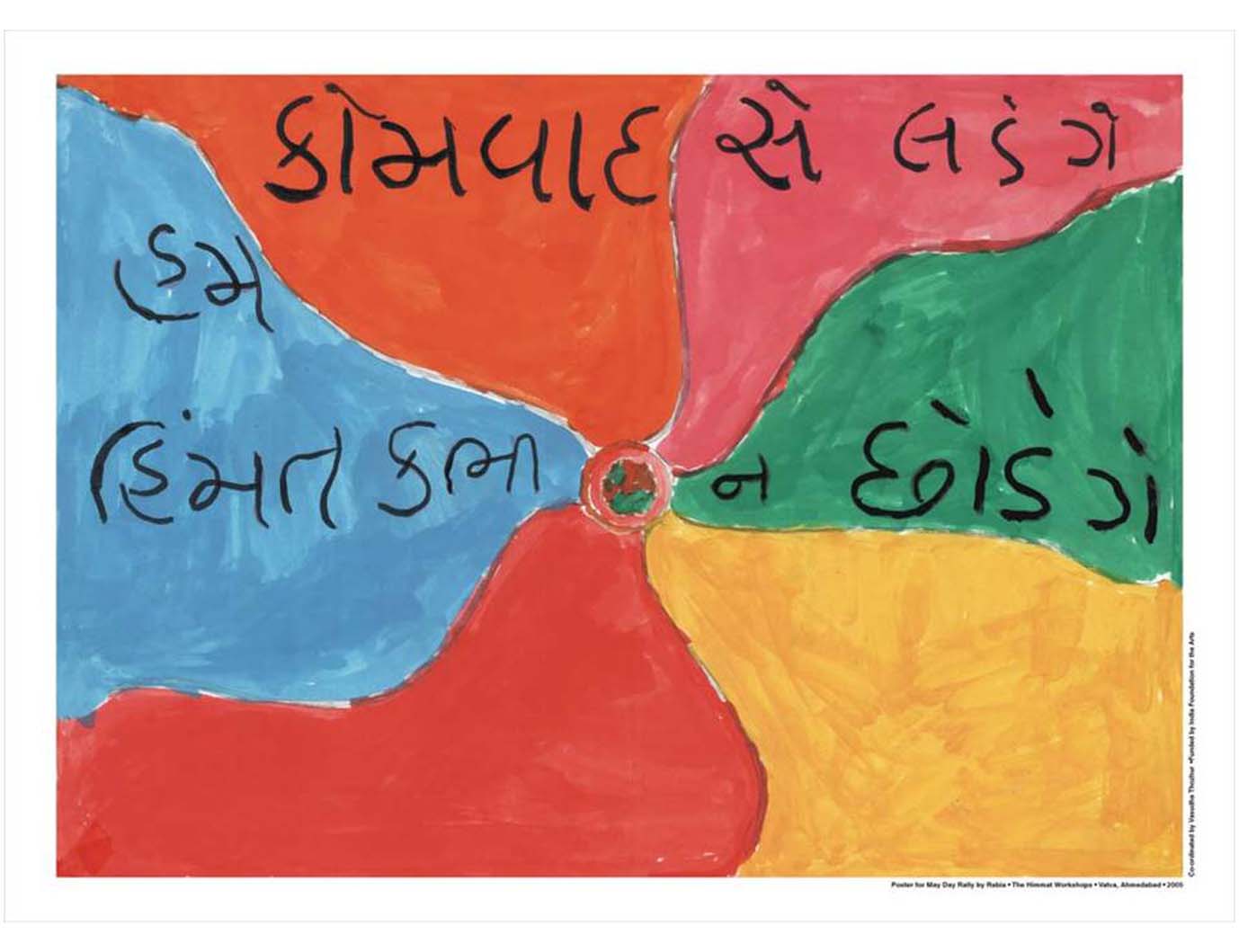

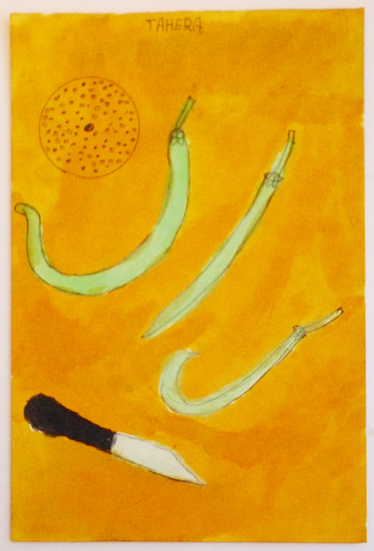

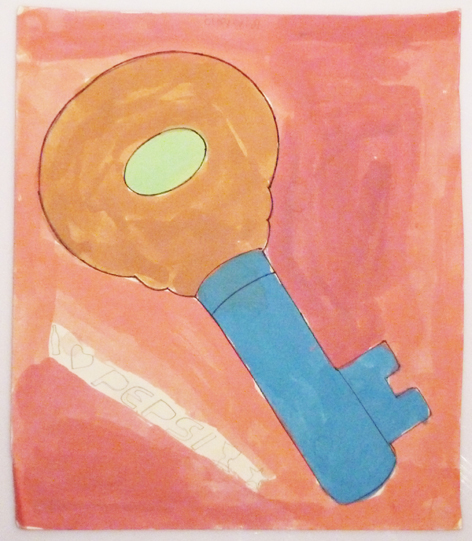

Image courtesy Gulammohammed Sheikh, Guftugu Issue 19

Image courtesy Gulammohammed Sheikh, Guftugu Issue 19

- A country where every person, whether Adivasi, woman, LGBTQ, organised or unorganised worker, can demand her rights to equality, dignity and a chance for a better life.

- A rational, secular country in which people are free to think; to doubt; to speculate and imagine; and always, to ask sharp questions.

The dream of remaking India remains alive in our hearts. So does the hope that fuels the dream, and promises us that it can be done. It gives us the courage, whether in the pages of Guftugu or elsewhere, to speak up in any way we can. The only constant is resistance.

Githa Hariharan

K Satchidanandan

May 2022

How do we grow our resistance everyday?

From the Editors

This editorial is short because it has been standing in long queues along with crores of honest Indian citizens before famished banks and empty automatic teller machines getting tired of pretending that it is battling black money and terrorism, while actually it was only helping fill the country’s coffers with enough money to be loaned out on low interest to the fat corporates surviving on human flesh and blood

This editorial is short because it is malnourished like the tribal children in the forests even from where they are being driven out so that the miners can deplete the hidden wealth of the country and amass unaccounted wealth

This editorial is short because it could not grow without water that is becoming scarcer day by day as it is the first casualty of all development schemes that fell trees and dry up the ground water and kill the rivers by sand mining

This editorial is short because it refuses to suck blood from the dalit in the village denied land and roof, food and water, education and freedom, ostracised, jailed and killed at the smallest of pretexts

This editorial is short as it fears that any time, with one more word, the noose may fall around its neck, or it will be shot dead like those who had upheld justice and reason, or lynched like those who had dared to eat the food that some consider treason

This editorial is short because it is a starving Muslim woman who lives in eternal fear of words as she can be divorced any time with a single word uttered thrice by the man who she had so far thought was hers

This editorial is short because, when language is used only to tell lies and sell the dictator’s image through advertisements that appear even in the guise of news, the less language one uses the less number of lies one tells

This editorial is short because it does not want to go on until it is forced to shout “Bharat Mata ki Jai” or to sing the national anthem which alone are considered the genuine acts of patriotism by people who have betrayed and divided the country and murdered the man who had united the people against her coloniser

This editorial is short because it is short of breath as the air around it has turned literally and metaphorically poisonous

This editorial is short…

This editorial…

This…

Githa Hariharan

K. Satchidanandan

February 2017

This editorial is short…

In Memory of Rohith Vemula (1989-2016)

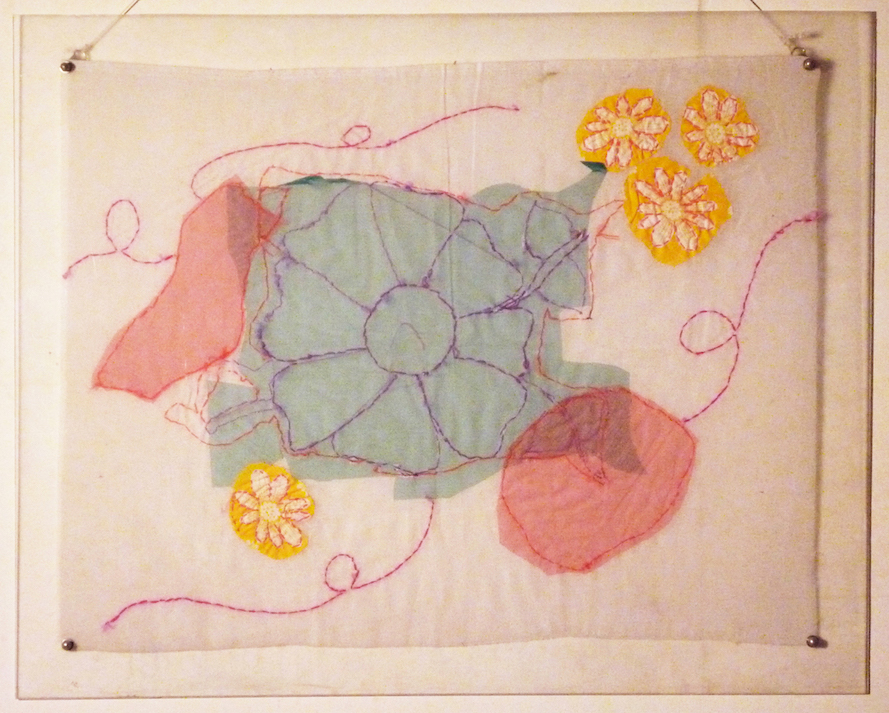

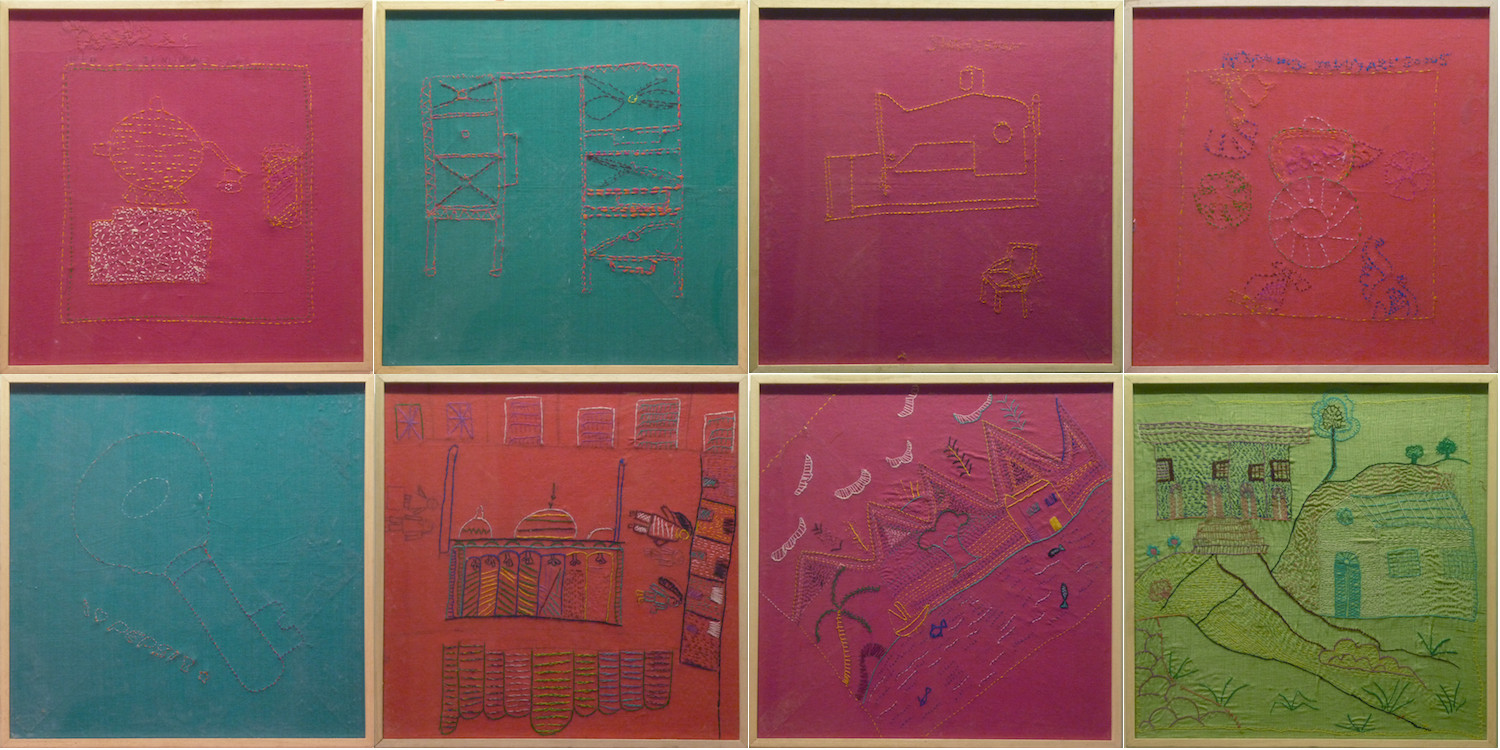

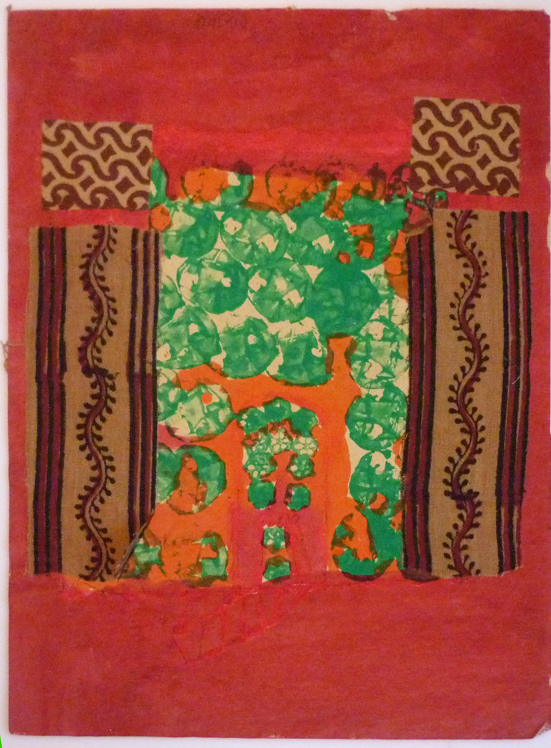

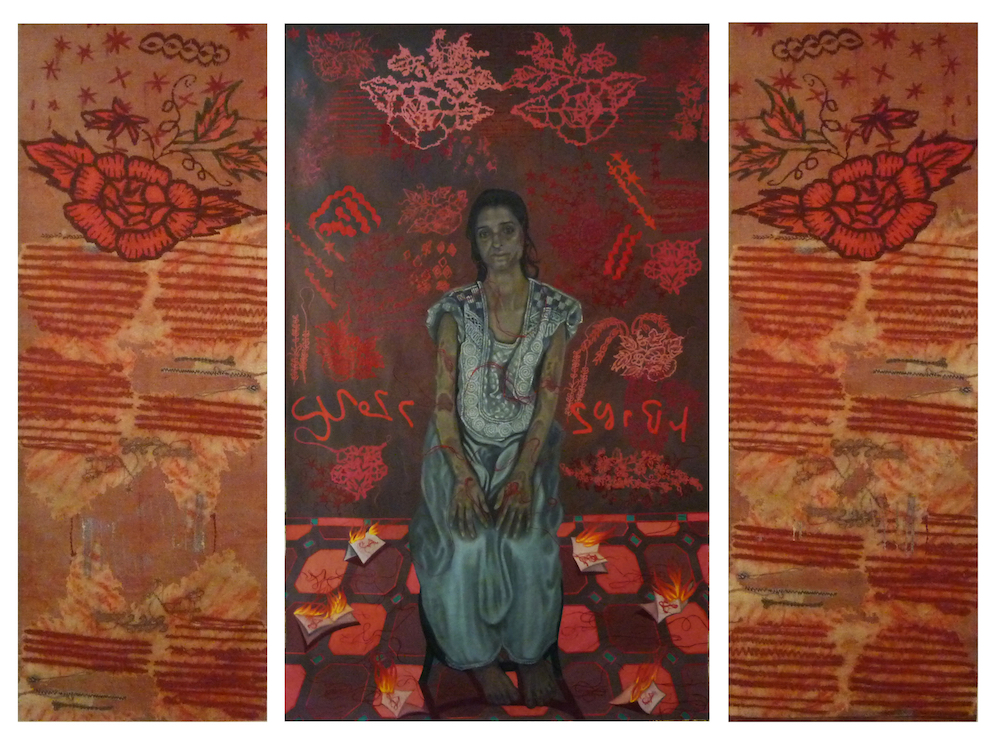

“Savi, as he is popularly known… [has] struggled to evolve a space for dalit art and imagery in the realm of art gallery exhibiting space… He is the first dalit artist in the country who has dared to aestheticise dalit themes in mainstream contemporary art practice. Savi challenged the boundaries of main-stream aesthetics in terms of weaving pictorial signifiers that… defies hegemony. His works are located in the realm of countering the Brahmanical hegemonic practices by articulating voice for the voiceless…”

Y. S. Alone, School of Arts and Aesthetics, Jawaharlal Nehru University, savisawarkar.blogspot.in

On the occasion of Rohith Vemula’s birthday on January 30th, Guftugu expresses solidarity with his life of struggle, and that of all the Rohiths in India today.

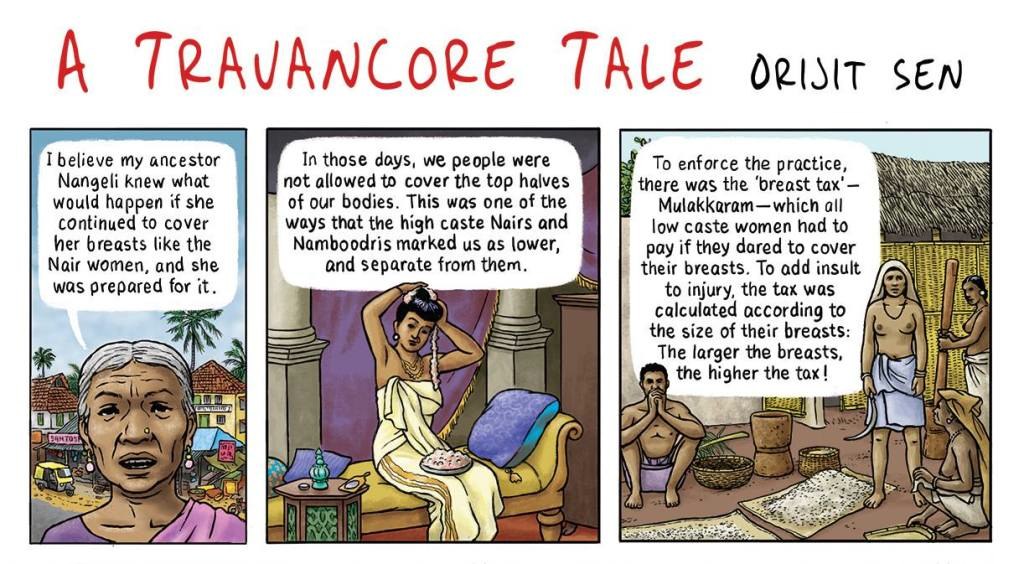

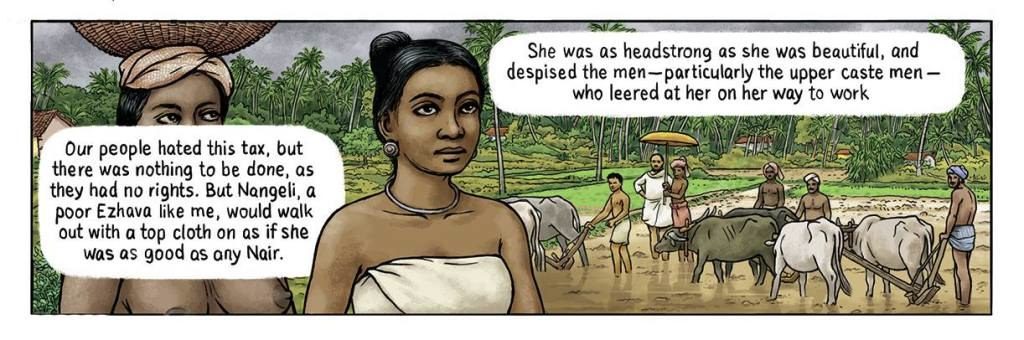

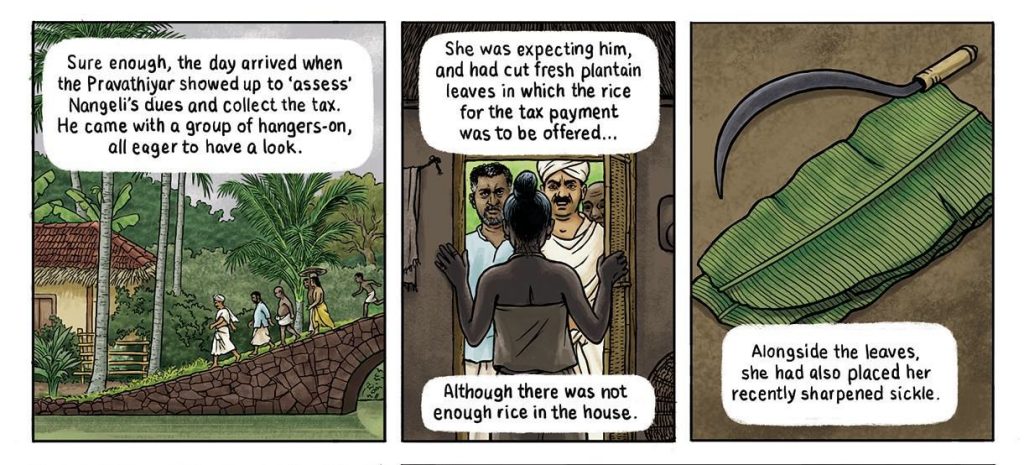

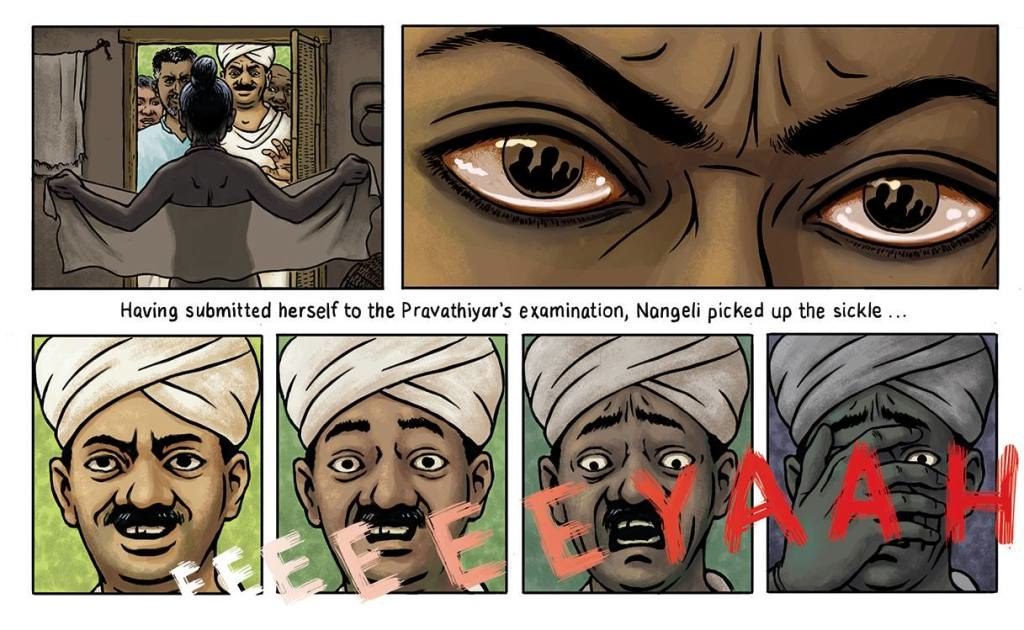

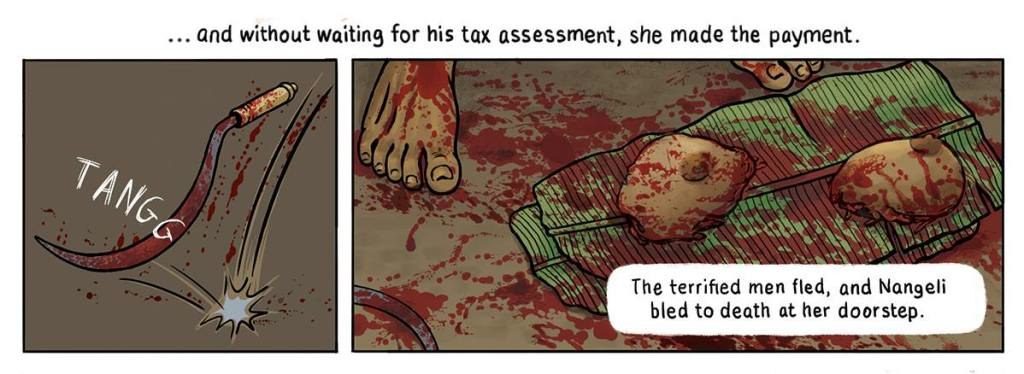

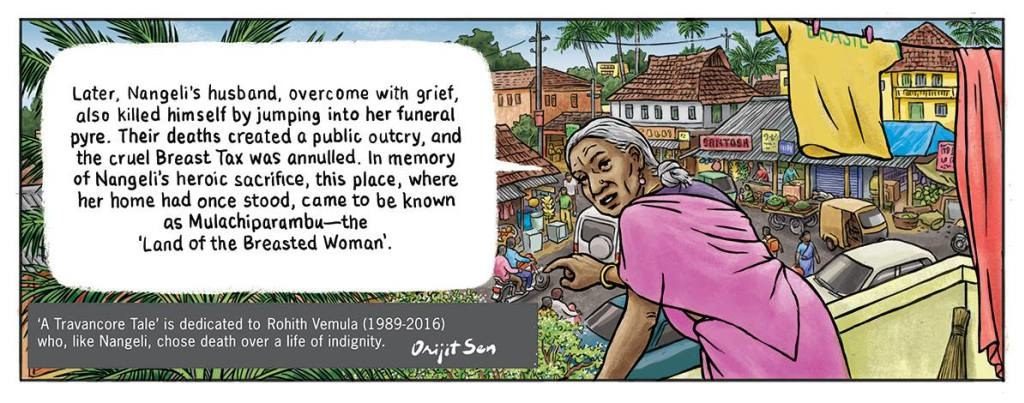

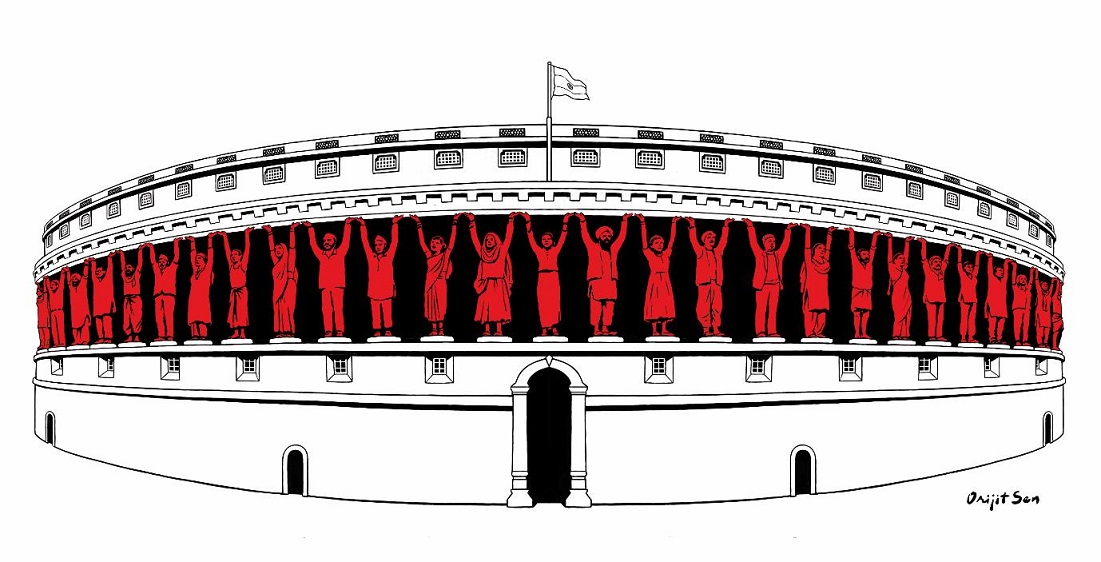

Artist Savi Sawarkar recounts dalit identity through a counter-aesthetic. Poet Meena Alexander reminds us of the texture of Rohith Vemula’s caste-defined life and death, with his last letter as the centre-point. Artist Orjit Sen dedicates to Rohith Vemula a graphic retelling of another story of resistance, that of Nangeli.

Meena Alexander

Death of a Young Dalit

In Memory of Rohith Vemula (1989–2016)

Trees are hoisted by their own shadows

BLANKAir pours in from the north, cold air, stacks of it

The room is struck into a green fever

BLANKStained bed, book, scratched window pane.

A twenty-six-year-old man, plump boy face

aaaaaSets pen to paper – My birth

Is my fatal accident. I can never recover

BLANKFrom my childhood loneliness.

Dark body once cupped in a mother’s arms

BLANKNow in a house of dust. Not cipher, not scheme

For others to throttle and parse

BLANK(Those hucksters and swindlers,

Purveyors of hot hate, casting him out).

BLANKSeeing stardust, throat first, he leapt

Then hung spread eagled in air:

BLANKThe trees of January bore witness.

Did he hear the chirp

BLANKFrom a billion light years away,

Perpetual disturbance at the core?

BLANKThere is a door each soul must go through,

A swinging door –

BLANKI have to get seven months of my fellowship,

One lakh and seventy thousand rupees.

BLANKPlease see to it that my family is paid that.

She comes to him, girl in a cotton sari,

BLANKHolding out both her hands.

Once she loosened her blouse for him

BLANKIn a garden of milk and sweat,

Where all who are born go down into dark,

BLANKWhere the arnica, star flower no one planted

Thrives, so too the wild rose and heliotrope.

BLANKHer scrap of blue puckers and soars into a flag

As he rappels down the rock face

BLANKInto our lives,

We who dare to call him by his name –

BLANKGiddy spirit, become

Fire that consumes things both dry and moist,

BLANKRuined wall, grass, river stone,

Thrusts free the winter trees

BLANKFrom their own crookedness, strikes

Us from the fierce compact of silence,

BLANKIgniting red roots, riotous tongues.

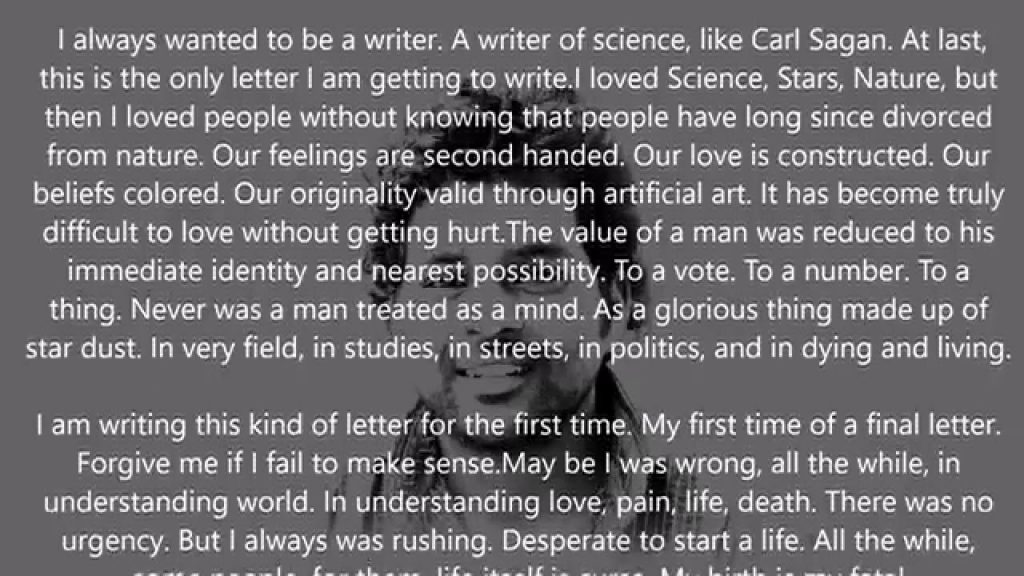

Courtesy i.ytimg.com

Courtesy i.ytimg.com

Writing this Elegy

When I was twenty-four I lived in Hyderabad. There was a neem tree in the garden of The Golden Threshold, once the home of the poet Sarojini Naidu. It is now the site of the new Central University. When time permitted, I would sit in the shade of that tree, shut my eyes and dream. Then, as now, images came to me, and I tried to craft a few lines of poetry.

I returned to the city several times. In early January 2016 I attended the literary festival. I met Nayantara Sahgal after a gap of many years. As I listened to her give the keynote address at the festival, I was inspired by her courage. I was learning afresh what it means to live in a time of difficulty, what it means to bear witness. Later that month, news came that a Dalit student at the university had killed himself – a tragic act of protest that resonated throughout the country. He left a haunting letter for us to read. I have included lines from his letter, and set them in italics in my poem.

Night after night as I worked on this elegy, the wind and winter chill commingled with the memory of rocks and stones and trees in a city I loved. I was consumed by the tumultuous hope and the very real despair of a young man I had never met.

Meena Alexander

Today, as in 2016, young people like Rohith Vemula still hear the message of a caste-ridden India: You cannot see your dreams soar. The message they hear bears the history of centuries of inequity; a thousand stories of barbaric humiliation. But equally important is the narrative of struggle – today, on the streets, in fields, villages, classrooms, courts, toilets.

This struggle also has a history in every part of India. In Kerala in the early nineteenth century, there is the story of Nangeli, who protested against one of the ugliest of oppressive taxes: the lower caste was only allowed to cover their breasts if they paid a tax, Mula Karam, to the government. Nangeli protested by giving the tax collector her breasts, cut off with a sickle. She died to bring an end to the breast tax system.

Orijit Sen

Remembering Nangeli on Rohith Vemula’s Shahadat day

Read related posts here and here.

Read more poems by Meena Alexander here and here.

See more work by Orijit Sen here, here and here.

Savi Sawarkar

Meena Alexander

Orijit Sen

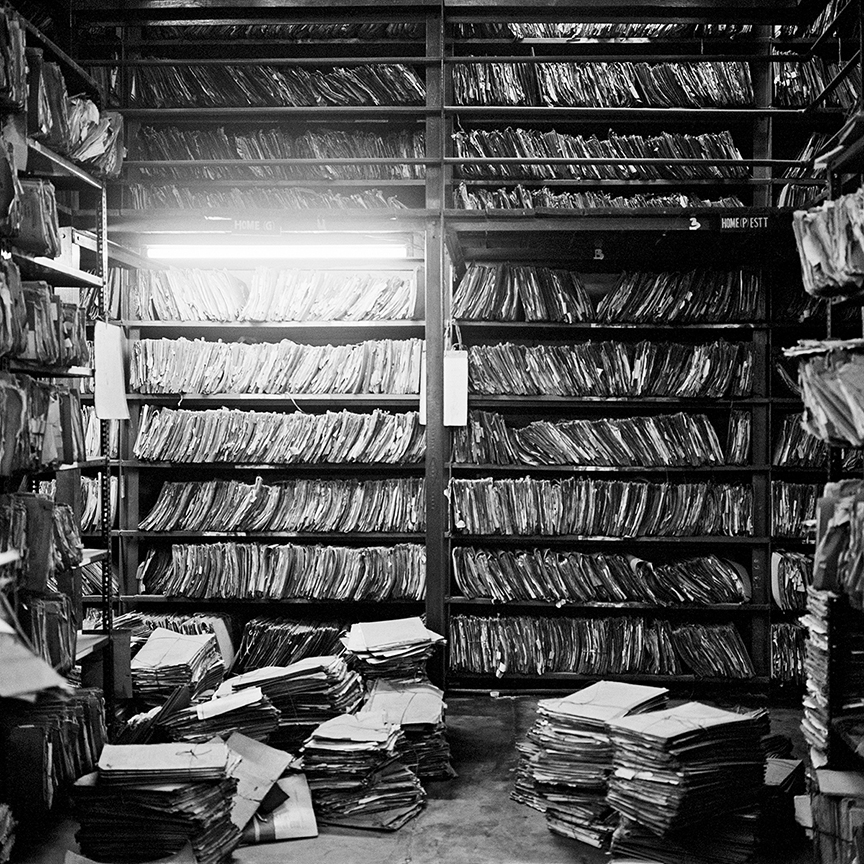

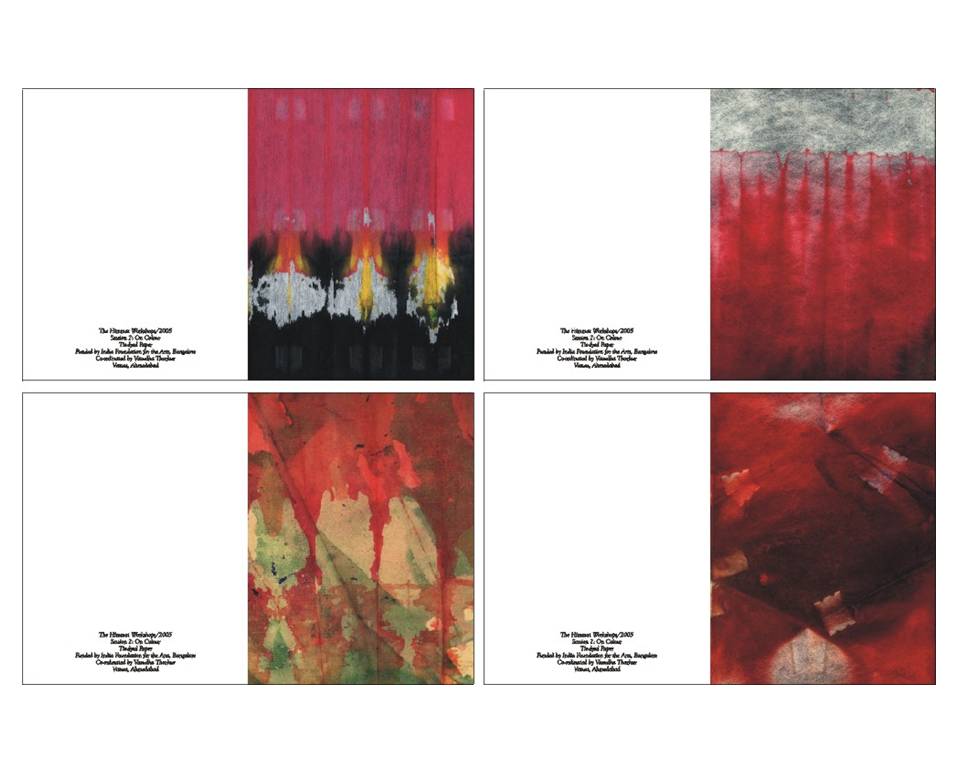

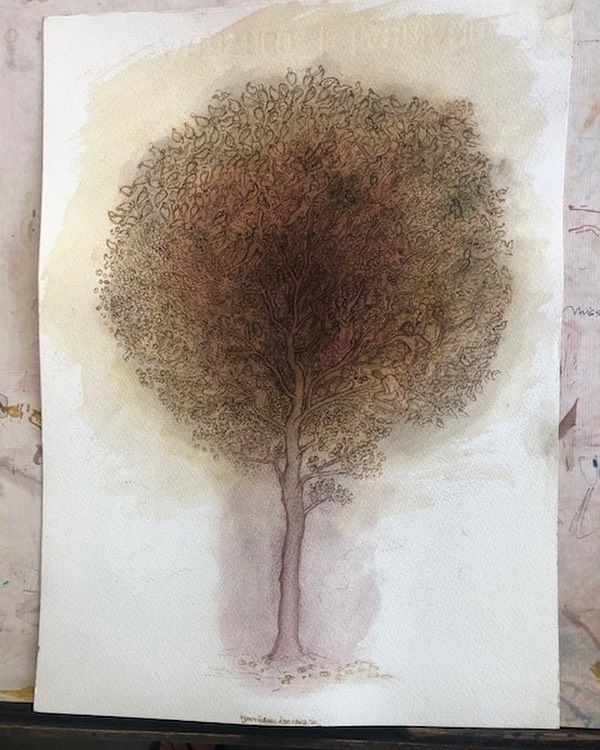

from File Room

Dayanita Singh’s ‘File Room’ is an elegy to paper in the age of the digitisation of information and knowledge. The analogue photographer and bookmaker has a relationship with paper that is integral not only to the work of making images, texts and memory, but also to a larger confrontation with chaos, mortality and disorder in the labyrinths of working bureaucratic archives in a country of more than a billion people. Including an interview with Hans Ulrich Obrist that relates this book with Singh’s other books and bodies of work, and texts by Aveek Sen that explore the different ways in which the world of files and paperwork continue to touch ordinary lives, ‘File Room’ is itself an archive of archives. It documents and reflects on the nature of paper as material and symbol in the work of making photographs and books.

Sea of Files from ‘File Room’, 2013

Even before we could put the furniture back in place where my husband’s body had lain, the call from the lawyer came. The high court had given a final date for a case my husband had been fighting against the government. Mahinder was a farmer who had developed a strain of wheat that created a world record in yields. But the National Seeds Corporation was disputing his way of distributing the seeds. So, even before the four days of official mourning were over, the space that was cleared for his body in the heart of our home in Delhi got swept up by the deluge of files that tumbled out of each room. And, in a moment, I turned into a 42-year-old widow with four young daughters and more cases than I could count on my fingers. Gone in an instant were my days of painting and poetry, of being happy simply running the house, photographing the girls, and making numerous albums.

People told me I should be wearing white. But who had the time to think about such mundane things? There was no time even for mourning. I had to file my reply to the court in four days. I had lived with files everywhere in the house ever since I married Mahinder, but I was clueless about their contents. We lived in a huge old house that seemed to grow in an organic way, according to a mad logic that had little to do with plans. It was an expanding maze of rooms leading to rooms, where stores of wheat-seed, trunks full of who knows what, cupboards full of rusty fire-arms and property deeds, two stuffed tiger-cubs in vitrines and a two-headed snake in formaldehyde coexisted with four girls and a woman who found no time to look for her widow’s weeds. And in the midst of all this were the thousands of files.

Revenue files, court files, income-tax files. They filled up not only the office-room, but also our bedroom, guestrooms and shuttered store-rooms behind the house. Most of that domestic chaos of paper had to do with land, lost, recovered and about to be lost again – the hundreds of acres lost during Partition, a fraction of those hundreds wrested from the State as compensation, and the constant threat of their decimation by inheritance laws favouring sons over daughters. Loss, division, and the inequality of the sexes threatened to swallow up even this house we had now. Then, all of a sudden, it fell upon me to keep it all together.

When Mahinder was alive, he would often get ready in the morning and call me, Locate this file of mine! Locate that file of mine! And I would be looking around in the office and in the bedroom, bending on my knees or on all fours to go under the large writing table that was covered with a mountain of papers. I would go under it and around it and with great difficulty locate a file for the high court, or was it some lower court? It was a game of hide-and-seek that I played with the files, always keeping my fingers nervously crossed. But, in less than a week in the summer of 1982, that youthful game turned decidedly grim. I inherited three high court cases and around eight cases in three lower courts in two cities. They involved 98 lawyers over a period of thirty years. Each day, we lived in dread of the doorbell ringing and our getting another notice or summons.

So, I brought all the mountains of files that were lying in Mahinder’s office, out of our bedroom and the store rooms, into the drawing room where he had lain at the end. I started to place the files all over the room. The piles grew and grew until they turned into a sea of files, at the centre of which I would sit. I had low blood pressure, so getting up early in the morning was like a punishment for me. To this was added something like a fear of waking up. If I opened my eyes a little at six in the morning, in a second all the worries would crowd back into my head. I sat with my tea in the middle of those files and started working. I had my breakfast there, and lunch, made notes until evening, and carried on until dinnertime. My daughters stood and watched me, but there was no time to explain. I wanted to protect them as much as I could. I often fell asleep on the files and most of my daughters would wake me with startled faces. Most of the files were dusty and old and had thin paper in them that crumbled quickly. Rats would gnaw at them too. Nobody was allowed to touch them.

I remember how my father’s files remained his strange, but known, bedfellows, after he had retired from the army and the police. They lay closer to him than even his beautiful, calm and faithful wife. They lay like bombshells, in piles and mountains, around his bed, which I had designed according to his specifications. No one dared dust them, or even touch them, lest the method in their madness was lost.

I had to work out a way of organising my files, keeping the plaints, applications, originals, copies and court orders separate, because once a piece of paper got lost in that vortex in the middle of the house it was impossible to find it again. In that kingdom of files, the battle was not between good and evil, but between order and chaos. An army of different files tried to keep the unruliness of paper under control. Box files, files with or without flaps, files which were just pieces of cardboard with pyjama strings fixed to them, ripple files, cobra files, lever files, index files, triple-extra-thick office files. They had names like Solo, Diplomat, Moot Point, Blue Sky and Moonlight.

Sometimes I had to make different combinations of papers for different lawyers and I would tag each combination with slips of paper and use page-marks of different colours, so that I could quickly get to what I needed in the rush of a courtroom. There were two long, deadly-looking needles of steel and iron, called a baksua, for punching holes in the papers, a job that demanded all my strength. Another punching machine looked like a large toad on the floor, and I put paper in its jaws and had to stand on it with the full weight of my body to make it punch holes. There were different kinds of paper too, each with its own smell and speed of decay: thin typing paper that crackled when you moved it and became crumbly in no time, court paper that was strong and watermarked, and cheap yellow-brown paper of which most of the court files were made, which quickly became brittle and grimy. At home, I started making my own bundles of files and papers, first with old sarees and then with markeen, the cheap cloth of unbleached cotton that sofa-makers nail to the underside of sofas. 1½ yards to make a bundle of files sit tight, 2½ to tie a body for the pyre, and worn by the eldest son as he lights the pyre and begins his mourning.

I soon started attending all the court hearings myself. This meant regular visits to the Tis Hazari and Patiala House courts, the high court of Delhi, and those terrible offices of the tehsildars and patwaris, dusty and dirty, with the huge stacks of files, old, half-torn and half-eaten, lying around everywhere. Who would ever manage to find a file in this mess? Yet, there would be an old man who knew exactly where, under which pile, to look for a file. Sometimes, I would peep into an empty courtroom and find a young woman typing away, sitting alone among helter-skelter chairs, the walls around her lined with steel cupboards and compactors full of files. After the courts closed for the day, there would often be long waits in lawyers’ offices. I kept one of Mahinder’s last-tied turbans in the car, and when I had to drive back home alone at night, I would put it on so that people might take me for a man at the wheel.

However much I hated files, at least mine were cleaner. I didn’t like the piles of dirty files lying about in heaps in the courts, so that I had to pick my way through them on the landings of the narrow backstairs. Imagine climbing three flights of stairs in Tis Hazari (there were no lifts then), clutching maybe ten files in my arms, which were more used to holding babies that were not quite as heavy. I would be standing in front of the office of some unsavoury old officer. There were no fans, so I was hot and sweating , and this man would be sitting inside nicely, not calling me in even after I had sent in a slip of paper with my name on it. People would walk in and out of the office, but I would stand at the door as if I were invisible. The files that I had to bring to court weighed ten or fifteen kilos, and I carried them in large canvas bags.

After some months, I got frozen elbows, especially on my left arm. My orthopaedic asked me if I was left-handed or had started playing tennis. Then, the real cause occurred to me. It took a great deal of stamina to run behind the lawyers in court. They were always in a hurry and ran ahead of me, their black coats flapping and flaring, and I would run behind them with a bag of files in each hand, trying to catch up. I did not mind when they said among themselves in the courts that I was not a woman, but a man.

Delay and waiting became the stuff of my life, keeping everything else on hold. Sometimes, my number came up too late in court, just before lunch-time. Would I be called again after lunch? No, sorry, at four o’clock the courts wind up, and I would have to wait for the next date, when I would come again carrying those files, and the hearing would again be adjourned to a later date, on which the lawyer for the other side wouldn’t turn up. Sometimes, there would be a bomb scare or a blast somewhere on the premises, and the courts would shut down suddenly.

During the anti-Sikh riots of 1984, as the mob approached our house with burning tyres late in the night of 30th November, I quickly destroyed the give-away nameplates with Mahinder’s name on them (Why must Sikh men have such long names? I wondered in my panic). I took the cheque-books and the jewellery from the cupboards, as I had seen my parents do during Partition, and made my daughters cross the road, one at a time, to the house of our courageous Hindu neighbour, who had offered to give us shelter. But I knew I had to go back and fetch the files. I waited until the mob was distracted by a passing bus, ran across the road and rushed back clutching my files. The bus was in flames. I suppose it had Sikh people inside.

If you walk about in the courts, you will realise in no time that everything in them is designed for waiting without hope. But you find yourself waiting with a stubbornness that begins to look like addiction to those who are out of all this. There are toilets everywhere, limbo-like waiting areas with rows and rows of chairs, stalls for books, magazines and food, even a dispensary. And the floors are identical to one another. If you climb a flight of stairs to the next floor, you would think you’re back in the same place again. Thank god, my cases are mostly in the high court, I thought. At least it is air-conditioned, and there are sofas I can sit on. I would go off to sleep on a sofa if I had worked until late on the files the night before, to be woken by a lawyer calling me to attend or, if that did not happen, to tell me to go home.

Every time people asked me, How are your cases? I would say, In the courts there is no justice, all you get are dates, dates and nothing but dates. Of the twelve or so cases I was fighting, I had won just one in these thirty years.

I used to think that I owed this fight to the ancestors who had left this land and property to us. They had left us their legacy, and it was my duty to pass it down to the next generation. But, sitting amidst the ocean of files late in the afternoon one day in that house of five women, with the now-quite-usual sickness rising up in my guts, I realized that this battle would never end. If I did not call it quits now, the only inheritance I would be handing down to my daughters would be this nightmare without end and my wilderness of files. People ask me why I gave up. To give up, I tell them, is the only way out of this country of perpetual stay orders, this land of status quo.

Aveek Sen

Dayanita Singh

Thinking and Counter-Thinking: On “Classical India”

I

It’s a great honour to be here in Heggodu.* I am very grateful to K.V. Akshara and K.V. Shishira for inviting me. I have been hearing about this place for almost twenty years. My teachers D.R. Nagaraj, U.R. Ananthamurthy, my senior colleague Ashis Nandy, Shiv Visvanathan, and many other friends have told me of this place. I’m thrilled and grateful to speak to all of you, to see this campus and get a glimpse of your activities here in this beautiful setting.

I am supposed to speak today on “Classical India”, and our overall theme is “Thinking and Counter-Thinking”. I am going to dwell very briefly on “Classical India” as a period of Indian history, after which I will complicate the notion of the “Classical”. What do we mean when we say “classical”? What do we understand by the word in our present time?

Anybody who has grown up in independent India has read about a time referred to as the “Classical Period” in our history textbooks. It dates roughly from the dawn of the first millennium, about 100-200 CE, to about 1100-1200 CE. It is effectively a time when Buddhism becomes salient and systematised. There is the flowering of a plurality of knowledge systems and literary canons in Sanskrit, Prakrit, Tamil and Pali, a period of argumentative vigour, continuing up to the emergence of major Islamic empires in the Indian subcontinent, when significant cultural shifts occur. This is what generations of Indians have been taught in our schools and colleges since Independence. So when I say “Classical India”, I’m sure, no matter what the regional language in which you received your secondary education, you will be reminded immediately of a few things.

You think of the Gupta Empire; the Cholas, Cheras and Pandyas in the South; the Chalukyas, Pallavas and Rashtrakutas in the Deccan. You think of Harshavardhan of Kannauj in central India; of Lalitaditya and Avantivarman, Kashmiri imperialists. You think of great poets like Kalidasa and Bhartrihari. You think of the Sanskrit epics, Mahabharata and Ramayana and in Tamil, Silappadikaram and Manimekalai. You think of cities like Ujjain, Vaishali, Amravati, Avanti. You think of poets, playwrights and prose-writers, like Bana, Sudraka and Bhavabhuti. You think of mighty philosophers like Nagarjuna, Ashvaghosha, Kumarila Bhatta, Shankara and Anandavardhana.

The stunning art, architecture and archaeological remains of Ajanta and Ellora, Kanchi, Badami, Aihole and Pattadakal; monumental treatises like the Bhagavadgita, Mimamsasutra, Brahmasutra, Yogasutra, Manusmriti, Kamasutra, Arthashastra, and Natyashastra; important schools of philosophy — Sankhya-Yoga, Nyaya-Vaisheshikha, Lokayata-Charavaka, Bauddha-Jaina, Mimamsa-Vedanta; the Shaiva, Vaishnava and Shakta sectarian streams; the massive classification of hundreds and thousands of learned texts by genre – smriti and shruti, itihasa and purana, shastra and kavya, agama and tantra, sahitya and darshana; the foundational discoveries of mathematicians and astronomers like Aryabhatta and Varahamihira; the rich and sometimes fantastic accounts of Chinese and Arab travellers like Fa Hien, Huen Tsang, Al Biruni; the great trans-Himalayan journeys of monks and scholars who carried the texts and teachings of the Buddha and the different schools of Buddhism northwards out of India; the expanding sphere of Indic influence in south-east Asia and the island cultures of the Indian Ocean. These are the myriad things — the vast civilisational detritus of a Golden Age — which come to your mind as the empirically verifiable referents of “Classical India”.

II

Now, let us begin to move beyond the immediate repertoire of references. When you use the word “classical” in the English language, it evokes a range of meanings in your mind. You are not always thinking historically about India (or some other part of the world, say Graeco-Roman civilisation), a thousand or 1500 years ago. When you go, for instance, to a classical music concert or classical dance recital, or to a classical theatre performance, chances are you would expect a certain kind of aesthetic experience if the artiste is good. The word “classical” qualifies your aesthetic experience, one that imparts both a sensation of pleasure and a knowledge of something that is true.

You might feel an overflow of emotions, rasa-anubhava, a sense of wonder, adbhuta, or even beyond, of miracle, chamatkara. You also gain knowledge through the experience, in listening to the music, or in watching the performance. If it is truly classical, there will be something in the rendering that changes your understanding of yourself and the world. It may come in a moment. You may not be able to express it in language. But you come away from that aesthetic experience changed to some degree. This is a meaning of “classical” that I’m sure all of you, as connoisseurs of the performing arts, as rasika and sahridaya audiences, are familiar with.

You also have certain expectations of the classical art-form itself. That it will be highly structured, rule-bound and difficult, impossible for an unskilled performer to practise, and not really accessible to an untutored audience. The barriers to entry are high on all sides, and involve years of training, rigorous discipline, continuous self-improvement — sadhana — riyaz — taiyyari. In Hindi we say “shastriya sangeet” for “classical music”, where the term shastra/ shastriya captures all of these aspects of the art, which take it out of the realm of the spontaneous. Many of you would have been to at least one performance of Bharatanatyam or Odissi dance, or Hindustani or Carnatic music. For most of us, one of these is what we mean when we say “the classical performing arts of India”.

A classical form that is not quite as popular, so to speak, is Kudiyattam, a recondite form of Sanskrit theatre performed in Kerala, which relies on embedded narrative, bodily movements, hand gestures, facial expressions, costumes, make-up, and continual percussion, but which has close to no linguistic register whatsoever (very few words are spoken or sung), and the minimum of instrumental music. It is extremely hard to practise or to watch, but utterly absorbing and uplifting once you get into it. Kudiyattam appears to be quite an ancient form, and is restricted to specific communities of performers, dancers as well as percussionists. Its root texts are episodes drawn from the Sanskrit Ramayana and the Mahabharata, but the accompanying commentarial texts — the screenplay versions as it were — as well as texts specifying and teaching hand, body and face gestures to actors and musicians, are in Malayalam. One act may be stretched out over two or three weeks of performance, with nightly sessions lasting two to six hours, sometimes even longer. To my mind, Kudiyattam is a sort of apotheosis of what we normally call “the classical”.

III

Now let us consider the “counter-thinking” on the classical, particularly in Carnatic music. The author of this counter-thinking is T.M. Krishna, one of the great living exponents of the form, often described as a prodigy, a genius and a maestro, someone who has been a speaker and performer right here in Heggodu. Krishna has attempted to deconstruct the label “classical” when applied to Carnatic music. He insists it be called “art music”, pointing out that while the characterisation “classical” suggests the form is very old, it is in fact modern, having taken no more, perhaps, than 100-300 years to arrive at its present juncture. He links the term “classical” to socioeconomic class and the caste system; for him, it is more accurately a sociological descriptor than an aesthetic one. He painstakingly prises open all the subtexts: the antiquarianism, Brahminism, patriarchy, sexism, elitism, nationalism, revivalism, and Hindu religious ideology lying buried in the seemingly value-free appellation “classical”, when it is attached to Carnatic music.

Contemporary Carnatic music, performed in the kutcheri concert space and format, is in Krishna’s account the outcome of a process of the gradual classicisation of a number of other styles, genres and ethics of performance that have in themselves almost disappeared from southern India, together with the marginalisation of the “holding communities” — principally Isai Vellalars and Devadasis — originally associated with them. Taken entire, Krishna’s critique of the classical is so powerful as to render the word’s typically positive connotation thoroughly suspect; in fact, he discredits the term quite comprehensively.

While he has not succeeded in replacing “classical music” with his preferred “art music” in how practitioners, critics, scholars and audiences refer to the form, Krishna has nevertheless unsettled the conservative world of Carnatic music to an unprecedented extent. His struggle with what he calls the “social re-engineering” of Carnatic music has led him to give up performing at the Chennai December concert season (called “Margazhi”) from 2015. Instead, he helps organise an alternative festival of the performing arts in the small fishing village of Urur Olcott Kuppam, which sits cheek by jowl with the bourgeois Brahmin neighborhood of Besant Nagar and Elliot’s Beach. This annual festival (“Vizha”) had its third iteration this month. Together with his friends, family, students and citizen volunteers, Krishna has launched a number of non-profit educational, pedagogic and outreach initiatives to bring this music to women and children, non-Brahmin castes, non-Hindu communities and socioeconomically deprived groups.

Krishna’s counter-thinking on the classical tends to shift our understanding of the locus of Carnatic music, from the stately immovable pinnacles of cultural power to a site of incessant social conflict (an external, historically-driven process) as well as continuous aesthetic negotiation (internal to the artiste’s relationship with the form). He has examined the musical careers of other Carnatic icons like M.S. Subbulakshmi, and Balamuralikrishna, who passed away recently. He takes a particular interest in how they departed from the conservative Carnatic received narrative, and the effects those departures had on their music. That Krishna himself comes from a Brahmin family, and remains constantly aware of the enabling role played by his own caste status in the spectacular success he has enjoyed from a young age, makes his public-spirited chastisements all the more agonistic.

Similar deconstructions of classical/ folk or classical/ popular binaries in a long tradition of socially responsible cultural criticism, from M.N. Srinivas and A.K. Ramanujan to U.R. Ananthamurthy, D.R. Nagaraj and K. Satchidanandan, backed up to varying degrees by the supposedly “harder” evidence of social science, cannot quite equal the moral anguish conveyed by a practitioner-theorist-historian-pedagogue like T.M. Krishna. His sheer artisitic virtuosity seems to grow in direct proportion to his evisceration of the social and political grounds of this music. It’s no joke to try to democratise the classical, particularly in India.

If it’s difficult to get people to see the classical as inseparably a product of its social context, and hence of the extreme inequalities inherent in that context, it is even harder to declassicise Carnatic music as a form. Krishna asserts that this music is intended as “art”, and not as “religion”; that its essence is shringara (beauty) and not bhakti (devotion); that even, say, the names and descriptions of deities and divinities in much of lyric canon of Carnatic music are meant to be primarily melodic and abstract, not lexical or religious. He does not deny the transcendent capacity of this music, but is adamant about dissociating this transcendence from God, or any specific god or goddess.

Lately, Krishna has been setting to music some “Virutham” poems penned by the contemporary Tamil writer Perumal Murugan, and singing them in his concerts. He also recently rendered a Muslim devotional song in Tamil, “Allahvai Naam Thozhudhaal” by E.M. “Nagoor” Hanifa. These are extraordinarily beautiful compositions, musically as accomplished and moving as anything Krishna sings. But their political intent is devastating, and doubly effective for being woven into an otherwise largely familiar and conventional Carnatic repertoire. A heart-rending complaint to Shiva by a fiction writer facing censorship, excommunication and intimidation, using the idioms of outcaste Tamil Shaivite poets from remote antiquity; or a prayer to Allah beseeching Him for compassion in a time of overwhelming Islamophobia — both go to the heart of what music is supposed to do: dissolve adversarial identities, enable mergers across ideological differences, break down our deepest ego barriers, and melt our most adamantine prejudices. Such songs, too, are extremely complex, subtle, and in the end far more subversive arguments, perhaps, than Krishna’s more obviously radical statements and positions on the caste, gender, and class vectors of Carnatic music. He takes aim at the classical simultaneously from the side of social structures, and that of aesthetic interventions. The classical in any conventional sense of the term cannot withstand this double-attack, and must disintegrate entirely.

IV

Sheldon Pollock, again someone familiar to you all here in Heggodu, has developed another way to understand the classical. This is through the idea of a crisis. He has been researching (in) many of the languages of pre-modernity in the Indian subcontinent, vernacular or classical, primarily Sanskrit and old Kannada. He says that there is a crisis in the classics. What is the classical? The classical is the site of a crisis. What is the nature of the crisis?

We have literally hundreds of thousands of texts in India, embodying different narratives, different genres of thought, different knowledge systems, and different kinds of expressions of consciousness and human experiences available to us. But a lot of them are in the pre-modern languages: Tamil, Sanskrit, Prakrit, or Persian; but also old Maithili, old Bengali, old Gujarati, old Marathi, old Kashmiri, Awadhi, Braj, or any of the South Indian languages, in their medieval or later forms.

We are inexorably losing the capacity to read these languages. We don’t have enough scholarship, or people who have been trained, in ways modern or traditional, to actually be able to decipher these texts, to retrieve the vision of the world available in them, and to make sense of the linguistic and epistemological diversity of our pre-modern cultures. And this is the case across the board, across religious sects and philosophical traditions, across knowledge systems, and across the classical languages of India.

Pollock, now 68, came to India as a young man in the early 1970s. He could still go to his guru, Pattabhirama Sastri in Varanasi, or other scholars in Chennai, Mysore and Pune, to read certain texts with them. But his teacher passed away and he himself has finished training two generations of students at the American universities where he has taught — Iowa, Chicago and Columbia. There may come a time when nobody is left of the traditional readers or interpreters, or the community of scholars who deal with texts in old languages. Sanskrit departments at our universities, Sanskrit colleges, our research institutes, archives and libraries, are all in a state of dysfunction and disrepair. Neither the government nor private philanthropy is investing enough to save these resources. Some study, teaching and discussion continue in religious institutions such as temples, sectarian gurukulas, mathas and monasteries, but secular scholarship of the philological kind is fast disappearing.

Between the time that my teacher, Sheldon Pollock, was a graduate student, and I myself was one, some 30 or 35 years later, Sanskrit pedagogy and scholarship in India have declined precipitously, even in old centres like Varanasi, Pune, Mysore and Chennai. There will come a time in the near future when we will lose our connection to the classical past, and we will simply not be able to decipher or read it. This is what Pollock describes as the “crisis in the classics”. Thus the classical becomes a site of worry, of loss, when you think about those hundreds of thousands of texts — lying in people’s homes, or in temples in villages and small towns, or even in the big national repositories to which we simply do not have, or shortly will not have access.

V

Currently the notable way to understand the classical — I think this is extremely important today, under the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) government at the centre — is that the classical is what essentially embodies India. In the pseudo-history of the Hindu Right, the classical period began once Buddhism had been assimilated into the Hindu fold, and ended as Islam, entering from the outside, came to dominate the subcontinent politically and culturally. In our public discourse, which we get from the print and electronic media, from popular history and pulp literature, and from specialist organisations like the Indian Council of Historical Research, the Indian Council for Cultural Relations, the Indira Gandhi National Centre for the Arts, etc., the classical is the treasure-house of civilisational value.

The classical is what we have to guard, defend, preserve and restore. It has been under siege, attacked continually by outsiders, non-Indians, “others”, “our” enemies, whether they were Muslims, European colonisers, or this modern globalised world, which doesn’t understand the peculiarities and special nature of Indian culture, Indian values or the “Hindu way of life”. We feel victimised that our classical achievements were overshadowed by invaders, and we need to reach back in the past and retrieve that long-lost glory.

Historical time moves away from the classical, and the work of Hindutva is to return us to the classical. In a sense, this ideology militates against the arrow of time. It is always in a state of defensive readiness. Here, the classical becomes the ground for the assertion of a religio-cultural identity. It becomes the source of a discourse of victimhood, resentment, and fear of civilisational and cultural “otherness” that is always in our midst.

Krishna’s deconstruction of Carnatic music from the perspective of its severe caste-class limitations, and Pollock’s anxieties about the dramatic erosion of the philological and epistemological capacities of India’s knowledge cultures, are both perfectly understandable and valid. They look objectively at the state of classical music and classical scholarship in the contemporary moment. But these critiques acquire a heightened urgency against the backdrop of the new culture wars being waged by the ruling Hindu Right dispensation.

Throughout the 20th century, fascist regimes across the world fetishised tradition, classics, the canon, the past. Paradoxically, their fixation on the classical is invariably combined with a populist contempt for intellectuals, scholars, and the actual skills needed for any informed engagement with history. Hindutva modelled itself on the nationalism of Garibaldi and Mazzini; its founding fathers openly admired Hitler and Mussolini, while its votaries continue to do so covertly even today. The BJP and the Sangh Parivar are thus no exception to what Umberto Eco identified as the pattern of “Ur-Fascism” (“Ur” in the sense of “original”, “primordial”, located at the very fount of Fascist ideology). Fascist classicism in the hands of Hindutva ideologues becomes another stick with which to attack religious minorities, homogenise the diverse cultures of our nation into a majoritarian Hindu Rashtra, and further marginalise the knowledge, arts and life-practices of the countless “little” traditions of India.

The culture warriors and internet trolls of the Hindu Right do not see Sheldon Pollock as the world’s foremost Sanskritist and historian of pre-modern Indic literary cultures. Instead, they see him as a person whose identity is American, white, Jewish, and Western. Should such a person be general editor of the Murty Classical Library of India? The library is endowed by Rohan Narayana Murty and published by Harvard University Press in a range of classical languages besides Sanskrit.

They do not like that T.M. Krishna, along with Bezwada Wilson — a leading campaigner for the eradication of manual scavenging by Dalits — won the 2016 Ramon Magsaysay Award. They try to counter Pollock’s argument for building the broad and reflexive discipline of “Critical Indology” with their agenda for constructing a narrow and nativist “Swadeshi Indology”. They are incensed by Krishna’s questioning of the religious and devotional intent of the great vaggeyakaras (composers of poetry and music) of the Carnatic tradition — Thyagaraja, Mutthuswami Diksitar and Shyama Shastri — and of his refusal to grant primacy to bhakti over sangeet, to linguistic meaning over musical significance.

In these circumstances, fresh thinking and counter-thinking about the classical, and activist interventions by practitioners like Krishna and Pollock, become an important part of the larger political project of dissent and resistance to which we are all, I hope, committed. Krishna has said that classical artists consider themselves to be above everyone else. They believe they exist on a higher plane, or float above the mundane concerns of work, livelihoods, markets, politics, caste, or any of the other practicalities of making art in the real world for all kinds of people. This is a false perception of the place of art and its role in society. We have to fall down, fall on the ground, he has said. Only then can we stand up again and rebuild the arts, and the socio-political cultures in which they are embedded, as open, egalitarian, democratic and meaningful.

It’s worth noting that when Krishna sings Carnatic music, or Pollock engages in Sanskrit philological scholarship, at no point can it be said that either is operating from any position but that of the greatest rigour, erudition, and accomplishment. The “classicism” of their respective disciplines is a given — the ancient lineages of texts and art forms; their sheer difficulty; their self-conscious and self-critical character; their strong sense of past history and future possibilities; their concern not just with beauty but perfection, nor elevation but transcendence; the years of unbroken engagement and the commitment to pedagogy required of the best practitioners; the innovative braiding of newly minted traditions and old civilisational memories — all these features of the “classical” are undeniable in both Sanskrit knowledge systems, and in arts like Carnatic, Bharatanatyam and Kudiyattam.

What is being argued, however, is that there is still a need to question and challenge the hidden violence, othering, and exclusion inherent in the cultural politics of the classical. There is every incentive — in fact, every reason — to continually revise, refresh, revivify and reinvent the canons of the classical arts and of classical scholarship. The greatest masters of what has been achieved are also the vanguard of what is yet to come. Radicalisation cannot be formal without also being contextual, aesthetic without being historical, epistemological without being political; it cannot be creative without also being responsible.

If some unimaginable catastrophe were to wipe out the Chennai Margazhi, the Murty Classical Library of India and the Nepathya Centre for Excellence in Kudiyattam of Margi Madhu Chakyar from the face of the earth, would India and the world be irreparably impoverished? Yes, of course. But that does not mean we accept that the doors of higher meaning will forever remain closed to the majority of people. Krishna has said that he began to be critical by asking, of himself and of his music, “What is beauty?” The most beautiful thing that human beings are capable of making is an equal society. If the classical can advance our collective journey towards the achievement of equality, then and only then is it worthy of our continued efforts towards its preservation and proliferation.

*This piece is an edited extract from, and an expansion of a lecture delivered on October 10, 2015 at the Ninasam Annual Culture Camp in Heggodu, Karnataka.

Ananya Vajpeyi

from The Logic of Disappearance – A Marx Archive, and Penal Colony

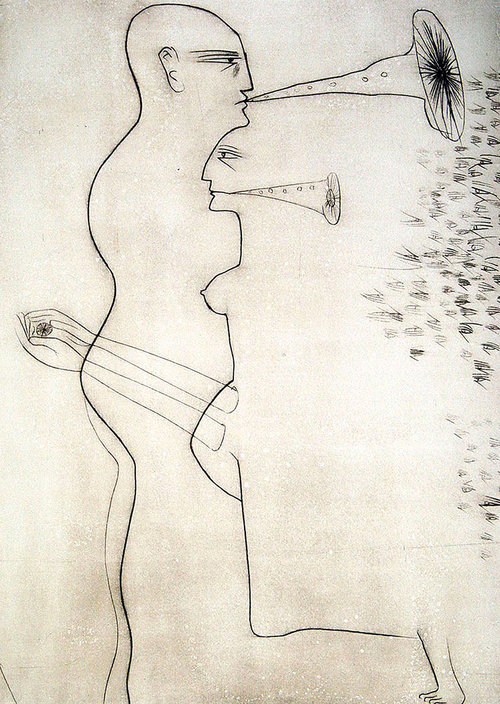

The first three drawings are selections from ‘The Logic of Disappearance – A Marx Archive’ (charcoal, 25 x 16″ each, 2014–).

The subsequent drawings are from ‘Penal Colony’ (charcoal, 20 x 29″ each, 2015–).

Images courtesy the Kiran Nadar Museum of Art, New Delhi.

K.M. Madhusudhanan

Judge Sa’b

If the Hindi isn’t displaying correctly you can download the pdf here. Jason Grunebaum’s translation appears below the original.

जज सा’ब

नौ साल हो गये, उत्तरी दिल्ली के रोहिणी इलाके में तेरह साल तक रहने के बाद, अपना घर छोड़ कर, वैशाली के इस जज कालोनी में आये हुए. यह वैशाली का ‘पाश’ इलाका माना जाता है. उत्तर प्रदेश की सरकार ने न्यायाधीशों के लिए यहां प्लाट आवंटित किए थे. ऐसे ही एक प्लाट पर बने एक घर में मैं रहता हूं.

जिस सड़क पर यह अपार्ट्मेंट बना है, उसका नाम है – ‘न्याय मार्ग’. हांलाकि इस सड़क में जगह-जगह गड्ढे हैं, हर तीन कदम पर यह सड़क उखड़ी-पुखड़ी है और कई जगह से ‘वन वे’ हो गयी है, क्योंकि बिल्डर्स ने कई जगह सड़क के ऊपर ही रेत, ईंटें, रोड़ी-गिट्टी, सरिया-पाइप के ढेर लगा रखे हैं. नतीज़ा यह कि हर रोज़ यहां ‘वन वे’ की वजह से एक्सीडेंट होते रहते हैं और कोई कार्र्वाई इसलिए नहीं होती कि बिल्डर्स और ठेकेदारों के पास बहुत रुपया और ऊपर तक पहुंच है.

इसी कालोनी में रहने वाले एक रिटायर्ड न्यायाधीश का पोता इसी ‘वन-वे’ पर एक डंपर के नीचे आ गया था और तीन महीने तक अस्पताल में रहने के बाद उसकी मौत हो गयी थी.

लेकिन वे बिल्डिंगें अभी भी बन रही हैं. डंपर और ट्रक अभी भी चल रहे हैं. वैशाली का ‘न्याय मार्ग’ अभी भी गड्ढों-हादसों से भरा हुआ ‘वन वे’ है.

वी.आई.पी. जज कालोनी बहुत तेज़ी से ‘डवलप’ होती कालोनी है. नौ साल पहले जब मैं यहां आया था, तब दो किलोमीटर की दूरी तक सिर्फ़ दो शापिंग माल थे. अब इक्कीस बड़े-बड़े बहुमंज़िला माल, दो इंटरनेशनल फ़ाइव स्टार होटल और शेवरले से लेकर ह्युंडई और सुज़ुकी कार कंपनियों के जगमगाते शो रूम हैं.

नौ साल पहले जब मैं यहां आया था, तब यहां जंगल और खेत हुआ करते थे. सरसों और गेहूं-बासमती के खेत. मोहल्लों में रहने वाले रुई धुनकने वाले धुनकिये, गोबर के उपले पारतीं औरतें, लोहे की कड़ाहियां, चिमटे, खुरपी बनाने वाले लोहार और उनकी कोयले की आग से सुलगतीं धौंकनियां, सबेरे-सबेरे सुअर का शिकार करने वाले लोगों के जत्थे, खुले में दिशा-फ़राक़त करती हुईं निर्लज्ज गरीब औरतें चारों ओर थीं.

पास में ही, नहर के किनारे-किनारे उगी झाड़ियों से सुनसान जगहें यहां ‘एनकाउंटर ग्राउंड’ हुआ करती थी, जहां ‘अपराधियों’ को पकड़ कर रात में पुलिस गोली मारती थी और अगली सुबह अखबार में डाकुओं या आतंकवादियों के साथ हुए पुलिस की साहसिक मुठ्भेड़ की खबरें छपा करती थीं.

लेकिन अब तो इन बीते नौ वर्षों में सब कुछ बदल गया है. जैसे किसी लंबी फ़िल्म का कोई बिल्कुल दूसरा शाट परदे पर अचानक आ गया हो.

इस कालोनी में बहुत से न्यायाधीश रहते हैं. कुछ रिटायर्ड और कुछ अभी भी अलग-अलग अदालतों में न्याय देने की नौकरी करते हुए.

बगल में ही एक पार्क है. सुंदर-सा. सुबह-सुबह जब कभी वहां घूमने जाता हूं, तो हर सुबह कई जजों से मुलाकात होती है. जो बूढ़े हो चुके हैं, वे अधिक चल नहीं पाते या फिर धीरे-धीरे छड़ी के सहारे चलते हैं. एक-दो के साथ उनका कोई सहायक भी होता है, उन्हें गिरने से बचाने के लिए. या अचानक दिल का दौरा पड़ने पर तुरंत उन्हें अस्पताल पहुंचाने के लिए. ये जज अब अपनी कोठियों में अकेले रहते हैं. कुछ अपनी पत्नियों के साथ और कुछ बिल्कुल अकेले. उनके बच्चे बड़े होकर दूसरे शहरों या देशों में चले गये हैं, जो साल-दो साल में कभी-कभार कुछ दिनों की छुट्टियों में यहां आगरा, शिमला, नैनीताल, दार्जीलिंग वगैरह घूमने आते हैं. एक अकेले रह गये बूढ़े जज का कहना है कि पता नहीं उनकी अमेरिकी बहू और उनके बेटे को इंडियन चिड़ियों का इतना क्रेज़ क्यों है कि जब भी दो-चार साल में वे आते हैं तो दो-चार दिन उनके साथ रह कर भरतपुर और राजस्थान की बर्ड्स सैंक्चुअरी देखने निकल जाते हैं. वे धीरे से कहते हैं, ‘पता नहीं क्या ऐसा है इन चिड़ियों में कि मैं अपनी ज़िंदगी, नौकरी, न्याय और अदालत से ऊब गया, लेकिन वे लोग चिड़ियों से नहीं ऊबे.’ इसके बाद एक लंबी उदास सांस भर कर वे कहते हैं, ‘मुझे अच्छी तरह से पता है कि मेरे बेटे और उसकी फेमिली मुझे नहीं, इंडिया में चिड़ियां और पुरानी इमारतें देखने आती है.’

इन बूढ़े जजों का इस तरह चलना देख कर लगता है, जैसे उनका पूरा शरीर अतीत की असंख्य स्मृतियों के वज़न से लदा हुआ है और यह उनका बुढ़ापा नहीं, स्मृतियों का भार ही है, जिसे वे संभाल नहीं पा रहे हैं और किसी कदर ढो रहे हैं. मैंने देखा है, अक्सर वे बहुत जल्दी थक कर पार्क में बनी किसी बेंच पर बैठ जाते हैं. वहां भी उनका माथा किसी बोझ से नीचे की ओर गिरता हुआ दिखता है.

बहुत भार होगा ज़रूर उसके ऊपर. ‘हार्डडिस्क’ भर चुकी होगी.

क्या वे अपने पिछले दिनों में किये गये किसी फ़ैसले के बारे में दुबारा सोच रहे होते हैं ? पछतावे से भरे हुए.

कई बार उनकी मिचमिचाती बूढ़ी हो चुकी आंखों से आंसू की कुछ बूंदें लकीर बनाती हुईं उनका चेहरा भिगा देती हैं. वे ज़ेब में रखा हुआ कोई बहुत पुराना, मटमैला हो चुका रूमाल निकाल कर झुर्रियों से भरा अपना चेहरा और चश्मा धीरे-धीरे पोंछते हैं.

लेकिन जो न्यायाधीश अभी भी उतने जर्जर और बूढ़े नहीं हुए हैं, वे पार्क में अपने जागिंग सूट और स्पोर्ट्स शू के साथ तेज़ कदमों से टहलते हैं. वे किसी न किसी जल्दबाज़ी में हैं. उन्हें शायद कोई फ़ैसला सुनाना है. कोई न कोई मामला उनकी अदालत में विचाराधीन है और वे उसकी गुत्थियां अपने टहलने की बेचैन रफ़्तार में सुलझा रहे होते हैं.

इन सभी जजों के पास बहुत से किस्से हैं. सैकड़ों-हज़ारों. अनंत. सच और झूठ के उलझे हुए ऐसे मामले, जिनके बारे में अपने दिये गये फ़ैसलों को लेकर उन्हें अभी भी असमंजस है. अगर मैं आपको उन सारे किस्सों को अलग-अलग सुनाना शुरू करूं तो एक कोई ऐसा उपन्यास बन जायेगा, जिसे पढ़्ने के बाद आपका विश्वास सच, झूठ, न्याय, अन्याय सबसे उठ जायेगा.

मेरा तो उठ चुका है इसीलिए दरगाहों, जंगलों, बच्चों और मंदिरों में ज़्यादा समय बिताता हूं. न्यायाधीश मुझे असहाय और न्यायालय कोई रोज़गार और वेतन देने वाले किसी बहुत पुराने माल या स्मारक की तरह लगते हैं.

ओह! लेकिन मैं किस्सा तो जज सा’ब का सुनाने जा रहा था, जिनका हमारे जज कालोनी में तो अपार्ट्मेंट नहीं था, वे कहीं दूसरी जगह, किसी दूसरे सेक्टर में रहते थे, लेकिन नौ साल पहले जब मैं यहां आया था, तब से उनसे मुलाक़ात होती रहती थी. उनका असली, औपचारिक नाम जो भी रहा हो, सब लोग उन्हें ‘जज सा’ब’ ही कहते हैं.

*

हर सुबह ठीक नौ बजे, जज सा’ब सुनील की पान की दूकान पर मिलते थे. हमेशा ताज़गी से भरे और मुस्कुराते हुए. पचास के कुछ पार रही होगी उनकी उम्र, लेकिन चश्मा नहीं लगाते थे.

‘नमस्कार ! कैसे हैं सर जी ?’ यह उनका पहला वाक्य होता था. ‘मैं ठीक हूं, जज सा’ब. आप कैसे हैं ?’ यह हमेशा मेरा पहला जवाब होता था. ‘मैं वैसा ही हूं, राइटर जी, जैसा कल था.’ यह भी उनका हर बार का उत्तर था.

‘हम सब भी वैसे ही हैं, जैसे कल थे !’ मेरे यह कहने पर जज सा’ब ही नहीं, सुनील की पान की दूकान पर खड़े सारे लोग हंसने लगते थे. यह भी हर बार का मेरा उत्तर था और सब का हंसना भी हर बार का हंसना था.

यह, सच था. चारों ओर सब कुछ तेज़ी से बदल रहा था, लेकिन हम सब, कल या परसों या और उसके पहले के दिनों जैसे ही थे. लगभग ज्यों के त्यों.

सुनील पानवाले की दूकान में हम सब के हर रोज़ इकट्ठा होने की वजह भी यही थी कि सुनील भी हर रोज़ पिछले रोज़ की तरह ही होता था. उसकी पत्नी को क्रोनिक दमा था और एलोपैथी, आयुर्वेद से लेकर जादू-टोना और जड़ी-बूटियों तक का सहारा वह ले रहा था. पांच बच्चे थे, जिनमें से तीन स्कूल जाते थे. दो लड़कियां, तीन लड़के. हर रोज़ वह स्कूल को गालियां देता था, जो किताब-कापियों के अलावा, जूते, मोज़े, बस्ता-बर्दी किसी खास तरह की, किसी खास ब्रांड और क्वालिटी की मांग करता था और अगर वह अपने बच्चों को यह सब जल्दी, किसी एक खास नियत तारीख तक खरीद कर नहीं दे पाता था, तो बच्चे स्कूल नहीं जाते थे. इस डर से क्योंकि वहां की मैडम उन्हें क्लास से भगा देती थी. वह उस बस को भी गालियां देता था, जो उसके बच्चों को स्कूल ले जाती थी और हर दूसरे-तीसरे महीने उसका किराया बढ़ जाता था. वह सरकार और पेट्रोल कंपनियों को गालियां देता था, जिनकी वजह से हर महीने पेट्रोल के दाम बढ़ जाते थे, जिससे उसकी पुरानी मोटर साइकिल का खर्च बढ़ जाता था. वह अपने बच्चों और पत्नी को गालियां देता था, जिनकी वजह से वह दिन-रात खटता रहता था और कभी अपने पहनने के लिए ठीक कपड़ा और पीने के लिए दारू का पउआ खरीद पाता था. वह पुलिस और म्युनिसपैलिटी को गालियां देता था, जो उसके पान के खोखे को हफ़्ता-बसूली के बाद भी, महीने-दो महीने में हटा देते थे फिर उसे अदालत में जाकर, जुर्माना भरना पड़ता था.

लेकिन उसने अपने साठ साल के पिता की बीमारी में सत्तर हज़ार खर्च कर के उनकी स्पाइनल के रोग को ठीक करा डाला था और वे फिर से चलने फिरने लगे थे. लेकिन अब वह अपने पिता जी को भी मां-बहन की गालियां देता था, क्योंकि उन्होंने गांव में जो ज़मीन बेची थी, उसमें उसको एक पैसा नहीं दिया था और सारी जायदाद उसके निकम्मे, गंजेड़ी भाई के नाम कर दी थी, जो बड़ी चालू चीज़ था.

सुनील यादव पानवाले की भाषा में इतनी अधिक गालियां थीं कि मैं अचंभे में आ जाता था. लेकिन अफ़सोस यह होता था कि ऐसी भाषा में राजभाषा ‘हिंदी’ का कोई साहित्य नहीं रचा जा सकता था. ‘हिंदी’ के शब्दकोषों और शब्द-सागरों में सुनील पनवाड़ी की भाषा के शब्द नहीं थे.

उसकी गालियां सुन कर हम सब हंसते थे क्योंकि हम सब अपनी-अपनी गालियों को अपनी-अपनी हंसी में हुनर के साथ छुपाते थे.

जज सा’ब तो सबसे ज्यादा हंसते थे. ठहाका लगा कर. कई बार, जब उनका मुंह पान से भरा रहता था और सुनील गालियां देने लगता था, जिसे सुन कर सब हंसते थे और जज सा’ब ठहाका मारते थे, तो पान की पीक उनके कपड़ों पर गिर जाती थी और तब वे भी बहुत गाली देते थे और फिर सुनील से चूना मांग कर पान की पीक के ऊपर रगड़ते थे क्योंकि इससे दाग छूट जाता था.

ऐसा ही कोई दिन था, जब वे अपनी सफ़ेद शर्ट के ऊपर पड़ी पान की पीक के दाग के ऊपर चूना रगड़ रहे थे, और तब पहली बार मैंने अचानक पाया कि पिछले दस महीने से हर रोज़, हर सुबह वे हमेशा वही एक सूट पहन कर वहां आते थे. शायद उनके पास कोई दूसरा सूट या कोट पैंट नहीं था.

सुबह वे इस तरह तैय्यार हो कर आते थे जैसे किसी कोर्ट में जाने वाले हों और अभी कुछ ही देर में कोई चार्टर्ड बस आयेगी और उसमें बैठ कर वे चले जायेंगे.

लेकिन जज सा’ब हमेशा पैदल ही लौट जाते थे. सुनील ने बताया कि वे अभी इंतज़ार कर रहे हैं. पिछली बार जब वे जज थे, उसकी मीयद बढ़ाई नहीं गयी है. जिस मंत्री की सिफ़ारिश पर वे किसी अदालत में जज बने थे, वह मंत्री किसी बलात्कार के केस में जेल जा चुका है और अभी तक वे कोई नया कांटेक्ट नहीं बना पाये हैं, जो उन्हें दुबारा जज बना दे.

उस दिन के बाद से मुझे उनसे सहानुभूति होने लगी थी और कई बार मैं उन्हें पास के ही पंडिज्जी के ढाबे में चाय पिलाने लगा था.

एक दिन वे सुबह नहीं, शाम तीन बजे सुनील की दूकान पर बहुत परेशानी की हालत में मिले. उन्होंने बताया कि उनका बेटा घर से भाग गया है और कहीं मिल नहीं रहा है. दो दिन से वे उसे खोज़ रहे हैं. थाने में भी उन्होंने गुमशुदगी की रिपोर्ट लिखाई है लेकिन ऐसा लगता है कि पुलिस वाले उनके सात साल के बेटे को ज़िंदा खोज़ने की बजाय कहीं उसकी लाश की इत्तिला पाने के इंतज़ार में हैं. यही अक्सर होता था. गुमशुदा बच्चे मुश्किल से ही दुबारा कभी मिलते थे. अक्सर उनकी लाश ही मिला करती थी.

गनीमत थी कि उस समय तक गैस आ चुकी थी और मेरी कार सीएनजी से चलने लगी थी. मैं भी चिंतित हुआ और जज सा’ब के बेटे को खोज़ने के लिए, उनके साथ वैशाली के सारे इलाकों में, उसकी जानी-अनजानी सड़कों, गलियों, मोहल्लों-बस्तियों में निकल पड़ा.

जज सा’ब कृतज्ञ थे और बार-बार उनकी आंखों में आंसू छलक आते थे. वे भावुकता में कभी मेरा हाथ थाम लेते थे, कभी कंधों पर झूल जाते थे. उन्होंने बताया कि पार्थिव को उन्होंने डांटा था क्योंकि वह पढ़ने की बजाय क्रिकेट का ट्वंटी-ट्वंटी मैच देख रहा था, जब कि सुबह उसका इम्तहान था. उन्होंने टीवी बंद कर दिया था, ठीक उस समय, जब डेलही डेयर डेविल्स को राजस्थान रायल्स से जीतने के लिए आखिरी चार ओवरों में पैंतीस रन बनाने थे और सुरेश रैना चौके छक्के लगा रहा था.

सुबह पार्थिव स्कूल के लिए निकला था और तब से लौट कर नहीं आया था. स्कूल से पता चला कि वह इम्तहान में भी नहीं बैठा था.

तो वह कहां गया ?

हम तीन घंटे से उसे हर जगह खोज़ रहे थे. कोई कोना नहीं छोड़ रहे थे. पांच से ऊपर बज चुके थे और डर था कि अगर अंधेरा हो गया तो आज का एक दिन और व्यर्थ चला जायेगा. दूसरी बात यह थी कि जज सा’ब अपने घर में अपने बेटे के साथ अकेले ही इन दिनों रह रहे थे क्योंकि उनकी पत्नी उनके घर, झांसी जा चुकी थी. वे दो वजहों से यहां रुके हुए थे. एक तो बेटे पार्थिव की पढ़ाई और परीक्षा और दूसरे, उन्हें पिछले दस महीने से हर रोज़, हर सुबह, यह उम्मीद लगी रहती थी कि शायद आज उनका काम कहीं बन जाय और वे दुबारा किसी जगह, लेबर कोर्ट ही सही, जज बन जांय. हर सुबह वे अखबार में राशिफल देख कर निकलते थे. मंत्रों का जाप करते थे. शनिदेव के मंदिर में तेल और सिक्के चढ़ाते थे. लेकिन हर रोज़ हर रोज़ जैसा ही होता था.

अब तक कार और पैदल हमने सारी समझ में आ सकने वाली जगहें खोज़ डाली थीं. हर जगह निराशा. वैशाली के चप्पे-चप्पे से खाली सूनी हारी हुई चार आंखें. अनगिनत लोगों से पार्थिव का हुलिया, उम्र, नाक-नक्श बता कर पूछे गये सवालों के जवाबों से हताशा.

…और तब, जब लगने लगा कि अंधेरा अब बढ़ जायेगा और रात उतर आयेगी, तब मुझे एक डरावना खयाल आया. नहर के किनारे-किनारे उगी झाड़ियों में पार्थिव की खोज़. जीवित न सही, जीवन के बाद का शरीर.

लेकिन समस्या यह थी कि मैं यह जज सा’ब से कहता कैसे ? इसलिए, बिना उन्हें बताये मैं कार नहर की ओर ले गया. यह हमारी आज की आखिरी कोशिश थी.

और वहां, जहां सरकारी ज़मीनों पर तमाम देवी देवताओं के मंदिर अनधिकृत ढंग से बने हुए. जिस जगह पर वैशाली की हरित पट्टी घोषित थी और जो अब ‘मंदिर मार्ग’ में बदल चुकी थी और जहां पहले पुलिस का ‘एनकाउंटर ग्राउंड’ हुआ करता था, वहीं नहर के किनारे के एक छोटी-सी खाली जगह में कुछ बच्चे क्रिकेट खेल रहे थे.

जज सा’ब अचानक चीख पड़े ; ‘राइटर जी, वो रहा पार्थिव !’

मैंने कार में ब्रेक लगाया. उसे सड़क के किनारे खड़ा किया और तेज़ी से भागते हुए जज सा’ब के साथ दौड़ पड़ा.

जज सा’ब अपने सात साल के बेटे पार्थिव के सामने खड़े थे, उसे अपनी ओर खींच रहे थे, उनकी आंखों से आंसू बह रहे थे लेकिन पार्थिव उनकी पकड़ से छूटने के लिए छटपटा रहा था.

उसके साथ खेलने वाले सारे बच्चे सहमे हुए चुपचाप जज सा’ब और पार्थिव की पकड़ा-धकड़ी देख रहे थे. मैं पांच कदम दूर खड़ा देख रहा था. तभी अचानक सारे बच्चों ने चिल्लाना शुरू कर दिया.

बच्चे डर गये थे. उन्हें लगा था कि पार्थिव का अपहरण हो रहा है. वे चीख रहे थे और कुछ ने जज सा’ब को ढेले मारने शुरू कर दिये थे. एक लगभग नौ साल का बच्चा दौड़ता हुआ आया और उसने क्रिकेट के बैट से जज सा’ब को मारा. निशाना सिर का था, उधर जिधर दिमाग हुआ करता है लेकिन ठीक उसी पल जज सा’ब झुके और बैट उनकी पीठ पर लगा.

शोर सुन कर आसपास लोग इकट्ठा होने लगे थे. मंदिर के कुछ पुजारी और साधू-भिखारी भी आ गये थे.

‘पार्थिव चिल्ला रहा था –‘मुझे इस आदमी से बचाओ ! प्लीज़… प्लीज़… हेल्प मी !’

शायद किसी ने फोन किया होगा क्योंकि हमेशा देर से पहुंचने के लिए बदनाम पुलिस की पी.सी.आर. वैन सायरन बजाती हुई वहां उस रोज़ ठीक इसी वक्त पर पहुंच गयी.

पार्थिव बार-बार कह रहा था – ‘मैं इन अंकल को नहीं जानता’ और जज सा’ब रोते हुए, उसे अपनी ओर खींचते हुए बार-बार लोगों की भीड़ और पुलिस को समझाते हुए कह रहे थे –‘ये पार्थिव है. मेरा बेटा.’

पुलिस के साथ, मैं और जज सा’ब थाने गये और फिर वहां से पार्थिव को घर ले जाया गया.

मैं भीतर से हिल गया था.

इसके बाद, अगली सुबह से जज सा’ब मुझे सुनील पानवाले की दूकान पर नहीं दिखे. आज तक वे नहीं दिख रहे हैं.

अब वे कभी नहीं दिखेंगे.

सोचता हूं काश यह इस किस्से का अंत होता. इसी असमंजस जगह पर आकर कहानी खत्म हो गयी होती.

लेकिन ऐसा नहीं हुआ. जज सा’ब की कहानी अभी बाकी है, जिसके बारे में पहले ही यह डिस्क्लेमर लगा हुआ है कि इसका किसी ज़िंदा या मृत व्यक्ति से कोई संबंध नहीं है. यह पूरी तरह काल्पनिक जगहों और पात्रों पर आधारित कथा है. और इसे पढ़ने से कोई कर्क रोग नहीं हो सकता.

*

यह संयोग ही था कि तीन दिन बाद मुझे विदेश जाना पड़ गया. पूरे तीन महीने के लिए और जब मैं वहां से लौट कर आया तो सुनील की दूकान उस जगह पर नहीं थी. उसके खोखे को वहां से म्युनिस्पैलिटी वालों ने हटा दिया था और उस जगह एल.पी.जी. का पाइप डालने के लिए गड्ढे खोद दिये गये थे और बाहर कंटीले तारों की फेंसिंग तान दी गयी थी. सड़क के पार जो एक लंबा-चौड़ा प्लाट खाली पड़ा था, और जहां कोलोनी का कूड़ा-कचरा फेंका जाता था, जहां लावारिस गायें, सड़क के कुत्ते, सुअर और कौओं की भीड़ जुटी रहती थी, वहां ‘शुभ-स्वागतम बैंक्वेट हाल’ का बड़ा-सा बैनर लग गया था.

जज सा’ब के बारे में मेरी स्मृति कुछ धुंधली होने लगी थी. इतने दिनों तक दूसरे देश के दूसरे शहरों की यात्राएं और बिल्कुल दूसरी तरह की ज़िंदगी. फिर यह भी एक संयोग ही था कि मुश्किल से पांच दिनों के बाद मुझे अपने गांव जाना पड़ गया.

तीन महीने बाद मैं वापस लौटा और लौटने के एक हफ़्ते बाद फिर से मुझे सुनील पानवाले की याद आई. याद आने की दो वजहें थीं, एक तो मेरे भीतर यह जानने की उत्सुकता थी कि उसकी पत्नी की तबियत कैसी है और बच्चों की पढ़ाई कैसी चल रही है. दूसरी वजह ज़्यादा महत्वपूर्ण और निर्णायक थी. वह यह कि मुझे किसी दूसरे पनवाड़ी के हाथ का लगाया पान खाने में वह स्वाद ही नहीं मिल रहा था, जो सुनील यादव के पान के हाथ का था.

पान खिलाने के पहले सुनील दूकान के नीचे रखी बोतल से पहले पानी पिलाता था –‘ल्यौ, पहले कुल्ला करके बिरादरी का पानी पियो फिर पान खाओ’ और फिर शुरू होती थीं उसकी धुआंधार गालियां.

वह भाषा मुझे सम्मोहित करती थी और मैं हमेशा सोचता रहता था कि कैसे इन गालियों को राष्ट्र-राज नव-संस्कृत भाषा ‘हिंदी’ के शब्दकोष और उसके साहित्य में सम्मिलित करूं. यह एक विकट-गजब की बेचैनी थी, जिससे मैं पिछले तीन दशकों से गुज़र रहा था. जब भी कभी मैं ऐसी कोई कोशिश करता और अपनी किसी कहानी या कविता में, सतह के ऊपर के वाक्यों में या उनके भीतर के तहखानों में छुपे अर्थों में किसी गाली का प्रयोग करता, मुझ पर हमले शुरू हो जाते. हाथ आये काम छीन लिए जाते. अफ़वाहें फैला दी जातीं और मैं फिर सही समय का इंतज़ार करने लगता.

उस समय और उस मौके का इंतज़ार, जब मैं खुल कर इन गालियों को अपनी रचनाओं में, एंड़ी से चोटी तक बेतहाशा इस्तेमाल कर सकूं.

यही वह कारण था कि मैंने फिर से सुनील का नया ठिकाना खोज़ निकाला और उसके पास जा पहुंचा. वह अब सेक्टर तेरह में जा चुका था और म्युनिसपैलिटी तथा पुलिस वालों को कुछ घूस-घास देकर पटरी पर इस नयी जगह का जुगाड़ कर लिया था.

मुझे इतने समय के बाद देख कर वह बहुत खुश हुआ. मैंने उसकी बोतल का पानी पीकर कुल्ला किया. उसके हाथ का लगाया हुआ पान खाया. हमारा मज़मा फिर जुड़ा. सब पहले की तरह ही थे. कुछ भी नहीं बदला था. सुनील की पत्नी को अब भी दमा था. उसे ठीक करने के लिए सुनील अब भी एलोपैथी, आयुर्वेद, जड़ी-बूटी, झाड़-फूंक, जादू-टोना, तंत्र-मंत्र का सहारा ले रहा था. उसके बच्चे अब भी स्कूल जा रहे थे. वह अब भी उसी तरह स्कूल, बस, पेट्रोल कंपनियों, सरकार, पुलिस सबको गालियां दे रहा था. इसी बीच कोई चुनाव हुआ था, जिसमें उसने अपनी जात के एक उम्मीदवार को वोट दिया था लेकिन अब उसे भी गालियां दे रहा था कि दूकान के लिए जब पटरी के ‘लाइसेंस’ की सिफ़ारिश के लिए वह गया तो उस नेता के पी.ए. ने उससे बीस हज़ार का घूस मांगा. वह गालियां देते हुए कसम खा रहा था कि अब आइंदा वह अपने किसी जात-बिरादरी के नेता को वोट नहीं देगा. सब साले चुनाव जीत कर चोट्टे हो जाते हैं.

उसकी गालियों पर हम सब अपने-अपने भीतर की गालियां, अपने-अपने हुनर से छुपा कर हंसते थे.

और तभी एक सुबह, जब सब हंस रहे थे मुझे जज सा’ब की अचानक याद आयी. उनकी याद आने की वजह थी सुनील की गालियां सुन कर उनके ठहाके के साथ उनकी शर्ट पर पड़ने वाली पीक के लाल धब्बे और उस पर उनका चूना रगड़ना.

फिर मुझे उस रोज़ उनके गुमशुदा बेटे पार्थिव और उसे खोज़ निकालने की घटना की याद आयी. और तब मैंने सुनील से जज सा’ब के बारे में पूछा.

सुनील ने जो बताया, वही इस किस्से का आखिरी हिस्सा है.

मेरे विदेश चले जाने के बाद, यानी पार्थिव की बरामदगी के लगभग छह-सात दिनों के बाद, एक सुबह जज सा’ब सुनील के पास अपना वही पुराना सूट पहन कर आये थे और उन्होंने उससे कहा था कि अब उनकी जज वाली नौकरी फिर बहाल होने वाली है, जिसके लिए उन्हें कुछ रुपयों का इंतज़ाम करने झांसी जाना है. वे बहुत खुश थे और उन्होंने कहा था कि दस-पंद्रह दिनों में वे झांसी से रुपयों का इंतज़ाम करके लौट आएंगे.

उन्होंने सुनील पानवाले से छह हज़ार रुपये उधार मांगे थे.

सुनील के पास रुपये नहीं थे तो उसने कहीं किसी कमेटी से उठा कर, महीने भर के ब्याज की शर्त पर रुपये लेकर उन्हें छह हज़ार रुपये दिये थे.

जज सा’ब पंद्रह दिन तो क्या ढाई महीने तक नहीं लौटे थे. कमेटी वाला हर रोज़ ब्याज बढ़ाता जा रहा था और अब सुनील की गालियां जज सा’ब के लिए निकलने लगी थीं. जज सा’ब उसे अपना मोबाइल नंबर और झांसी के घर का पता लिख कर दे गये थे. लेकिन सुनील जब-जब उस मोबाइल नंबर पर फोन करता, उसका ‘स्विच आफ़’ मिलता.

जज सा’ब भी चोट्टा था, साला. पनवाड़ी को ही चूना लगा गया. वह कहता, तो सारे लोग उसी तरह हंसते. अपने-अपने हुनर के भीतर अपनी-अपनी गालियों को छुपाते हुए.

फिर ब्याज पर ब्याज की राशि जब ज़्यादा बढ़ गयी और कमेटी वाले ने थाने में शिकायत कर दी और पुलिस वाले आकर उसका खोखा उठा कर थाने ले गये तो जज सा’ब की खोज़ में सुनील झांसी गया.

झांसी में जज सा’ब का घर खोजने में सुनील को आठ घंटे लग गये. बीच-बीच में उसे लोगों ने भी बताया कि यह पता शायद नकली है, जिसे सुन कर सुनील एकाध बार झांसी जैसे अनजान शहर में, जहां वह पहली बार ही गया था, रोया भी था और वहां भी उसने अकेले में भरपूर गालियां आंसुओं के साथ दी थीं.

झांसी में वैशाली का मज़मा नहीं था, जो हंसता.

आखिर कार शहर से सात किलोमीटर दूर वह मोहल्ला मिला और वह घर, जिसका नंबर जज सा’ब ने सुनील को अपने पुराने लेटर हेड पर लिख कर दिया था. वह लेटर हेड पुराना था. उस समय का, जब वे जज हुआ करते थे. उस पर तीन मुंह वाले शेर का छापा ऊपर लगा था.

लेकिन उस घर में ताला लटका हुआ था. सील बंद, सरकारी ताला.

सुनील के होश उड़ गये.

बहुत मुश्किल से एक पड़ोसी ने जो बताया, वह कुछ बहुत ही मामूली से वाक्यों के भीतर था. उसे बताते हुए पड़ोसी का चेहरा लकड़ी जैसा सपाट था.

जैसे वह किसी कठपुतले का चेहरा हो.

‘यहां रहने वाले ने फेमिली के साथ सुसाइड कर लिया. दो महीने पहले. पुलिस ताला लगा गयी है. अभी तक यहां उसका कोई रिश्तेदार नहीं आया.’

सुनील पहले तो स्तब्ध हुआ, फिर रोया और फिर उसने खूब गालियां बकीं, जिन्हें सुन कर उस सपाट चेहरे वाले कठपुतले को भी खूब हंसी आई, जिसे उसने अपने किसी हुनर के भीतर नहीं छुपाया.

सुनील ने अपने गांव जा कर अपने पिता जी, जिनके स्पाइनल के इलाज में उसने सत्तर हज़ार खर्च किये थे और आठ महीने की दिन रात सेवा, उनसे ड्योढ़े ब्याज की दर पर दस हज़ार का कर्ज, रोटरी के स्टैम्प वाले कागज़ पर हलफ़नामा लिख कर उठाया और उसमें से साढ़े सात हज़ार कमेटी वाले को और दो हज़ार पुलिस और म्युनिस्पैलिटी वाले को दे कर अपना खोखा फिर से पटरी पर लगाया.

यह बात बता कर सुनील ने फिर से अपनी गालियां शुरू कीं, जिन्हें सुन कर मैं हंसा और हमारे मज़मे के सारे लोग हंसे लेकिन इस बार पान की पीक मेरी शर्ट पर गिरी और मैंने सुनील से मांग कर वहां चूना रगड़ने लगा, जिससे वहां पीक के धब्बे न रहें.

अचानक मैंने देखा कि मेरी शर्ट भी, जिसे मैंने पहन रखा है, वह लगभग अट्ठाइस साल पुरानी है.

आपको याद होगा कि मैंने अपने और जज सा’ब की दो एडिक्शंस या लतों के बारे में बताया था, जिसकी वजह से हम एक-दूसरे से जुड़े हुए थे. एक पान और दूसरी खैनी. और तब मैंने कहा था कि अपनी और उनकी तीसरी लत के बारे में मैं कहानी के बिल्कुल अंत में बताऊंगा.

…तो वह तीसरी लत या एडिक्शन थी ज़िंदगी.

हर हाल में ज़िंदा रहे आने की लत.

सुनील, वहां इकट्ठे होते लोग, सारा मज़मा इसी ‘एडिक्शन’ का शिकार था, लेकिन जिस लत के कारण कोई कर्क रोग नहीं होता. यह खैनी-सिगरेट-गुटके की तरह जानलेवा नहीं है.

भले ही जज सा’ब की जान चली गई हो.

Eugène Cicéri, Design for a stage set at the Opéra / Metropolitan Museum

Eugène Cicéri, Design for a stage set at the Opéra / Metropolitan Museum

Judge Sa’b

Nine years ago, after thirteen years of living in the Rohini neighbourhood of North Delhi, I moved, and came here, to Judge Colony in Vaishali, just outside the capital. Vaishali is considered a ‘posh’ neighbourhood, where the provincial government of Uttar Pradesh had set aside plots of land here reserved for judicial magistrates. And it’s in one of the houses built on one of those plots where I now live.

The street where my apartment was built is called ‘Justice Way’, though potholes are everywhere and every few feet the road is torn up and littered with pits. Builders have strewn piles of bricks, construction sand, asphalt, rebar, and PVC pipes all over the road, and it’s one-way for several stretches. Accidents happen daily because of its having become a one-way street. The street’s never fixed because the builders and contractors have plenty of cash, and connections that go all the way to the top.

The grandson of a retired magistrate, living right here in Judge Colony, was hit by a dump truck and spent three months in the hospital before he died.

But the buildings are still going up, and the dump trucks and lorries still come and go. ‘Justice Way’ in Vaishali is still full of potholes, rife with accidents, and still one-way.

Development in this Judge Colony for VIPs is happening incredibly fast. When I first moved here nine years ago, there were only two shopping malls within a two-kilometre radius. Now there are twenty-one gigantic, multi-storey shopping malls, two five-star international hotels, car showrooms, shiny and grand, selling every car from Chevrolet to Hyundai to Suzuki, a Haldiram sweet shop, McDonalds, Domino’s Pizza, KFC, Bikanerwala, and hundreds of other fast food and snack joints. There’s a restaurant or bar every two feet.

In my sixty years, I’ve never seen so many who are more well-drunk than well-fed.

There was only forest and farmland when I moved here nine years ago: mustard fields, fields of wheat, and basmati rice paddies. Sometimes the whole area would be filled with the fragrance of yellow mustard blossoms or the scent of basmati. Around the neighbourhood you’d see cotton combers hand-scutching cotton wool, women making cow-dung cakes, hammersmiths forging karhai pots and pans and tongs and sickles, the morning gang of pig hunters, and slum women everywhere answering the call of nature right out in the open. I wasn’t quick to go out on my balcony in the morning since the empty lot across the street was where man and woman, alongside swine, performed their daily excretions in full view of anyone looking. And just beyond is the scrubland along the bank of the canal that had become ‘encounter grounds’ where ‘criminals’ were taken under the cover of night and shot dead by police. Newspapers the next morning ran stories of the police’s lively and heroic encounter with terrorists or dacoits.

But as nine years have passed, everything’s changed. As if, while watching a very long film, a completely different, startling shot suddenly leaps on screen.

There are a great many magistrates living in this colony. Some are retired, others still cashing a paycheck for meting out justice in their various respective courts.

There’s a park right next door to me, and a lovely one at that. Whenever I’m out on a morning walk in the park, I inevitably run into several judges. Some are already quite old and aren’t able to walk very far or very fast, or they shuffle along with a cane. A few have a caregiver alongside to make sure they don’t fall, or to take them straightaway to the hospital in case of a heart attack or shortness of breath. These judges live alone in their quarters. Some with their wives, and others completely alone. Their kids are all grown up and have moved away to other cities in India, or somewhere abroad, and maybe come to visit India once every year or two for a handful of vacation days of sightseeing in Agra, Shimla, Nainital, Darjeeling or the like. One judge living all alone told me he can’t wrap his head around why his son and his American daughter-in-law are so crazy for Indian birds, so much so that during their biennial visit, after staying with him for a couple of days, they rush off to Bharatpur or other bird sanctuaries in Rajasthan.

‘I can’t figure out how it is that those two never tire of birds when I am fed up to here with my life, work, the law, and courts,’ he said, scratching his head with a sigh. ‘Believe me, I’m no fool, I know my son and his family come to India to see birds and monuments, not to spend time with me.’

Watching the gait of these old judges it seemed as if their whole bodies bore the load of the countless memories of the past. It wasn’t old age, but the burden of memories they couldn’t bear – but had to shoulder nonetheless. I noticed that they’d quickly tire and sit on one of the park benches where there, too, their heads bowed downward under the strain.

It must be an unfathomably heavy burden carried behind their ancient brows, rutted with deep lines and wrinkles. Their internal ‘hard drives’ must be filled to the max.

Might they now be thinking again about decisions they’d handed down in bygone days, possibly with pangs of regret?

A few teardrops ran down their faces from old, tired, blinking eyes, irrigating wrinkles and wetting their cheeks. And when it happened, they would find a soiled old handkerchief from inside their pockets, using it to wipe a rutted face and slowly clean dirty eyeglasses.

But the magistrates who weren’t yet so old and infirm donned their jogging suits and sporty trainers and walked at a brisk pace in the park. They were in some kind of hurry, possibly about to hand down their decisions. Some case or another was still underway and they were trying to sort out the boondoggle with their anxious gait.

Each and every one of these judges had a great many stories to tell – hundreds, thousands, an unending reserve. Cases where truth and falsehood were so knottily entangled that even today they’re unsure about the decisions they’d handed down. If I were to start telling you each of these various stories it’d soon become an epic tale that would quickly eviscerate your notions of truth and falsehood, justice and injustice.

My own faith is long gone – that’s why I spend more and more time in temples and dargahs, with trees and children. A magistrate strikes me as friendless, all alone in the world, and a court of law like a shopping mall or tourist monument: a place that exists to give them a wage.

Oh! But I was going to tell you the tale of Judge Sa’b, whose apartment isn’t even in our Judge Colony, but in another place, another sector. Still, when I came here nine years ago I used to see him all the time. Whatever his official, real name might have been, everyone called him ‘Judge Sahib’ – shortened in our slangy way to ‘Judge Sa’b’.

I always met him at Sunil Yadav’s paan stall. Paan and chewing tobacco: the bad habits that bound the two of us together.

There was one more addiction or habit that he had. (I’ll reveal it at the very end of the story. And, I think it’s important to give a ‘disclaimer’ right here and now that this story has no connection with persons, living or dead, and is purely a fictitious work based on imaginary characters and places. If it looks like it does, it’s no more than sheer happenstance, and if someone decides to file a lawsuit, it will be heard in the court where Judge Sa’b presides.)

So please come and listen to the real story. It’s not long at all, and has a whiff of the sensational about it.

Every morning right at 9 a.m., I met Judge Sa’b at Sunil’s paan stall. He was always smiling and sprightly. He had surely crossed into his fifties, but still didn’t wear glasses.

He always opened with the very same sentence. ‘Namaskar, sir ji! And how are you today?’ And my answer was invariably, ‘I am just fine, Judge Sa’b, and you?’ His response, unfailingly, was, ‘My dear writer, I am the same as I was the day before.’

‘And that’s the same with all of us, same as we were the day before!’ Judge Sa’b and everyone else standing around Sunil’s smiled at this. My answer and the group’s mirthy reaction were both always the same.

It’s the truth. No matter that everything all around was changing so quickly, each one of us – whether yesterday, or the day before, or the days before that – were exactly the same. Same as we ever were, more or less.