Tyranny (in any form) is always temporary. Its weakness lies in its legitimacy being derived from the enforcement of a single doctrine, dogma and book. All it takes is a dissident or alternative idea to take root; paper will always trump rock. The singular will always breed acts of resistance in print, and often they take a quieter, more resilient form. Under the USSR, the Soviet bloc and Warsaw Pact nations suffered the longest modern period of state censorship and oppression. Yet novel and eventually successful forms of counteraction also marked this period. The underground printers who flourished in Amsterdam, printing the banned works of Spinoza and his contemporaries, are part of just one historical moment in the legacy of print as disaffection, resistance, solidarity, action, and self-determinism. I am struck, as always, by acts of quiet, almost passive, resistance to some of the most violent forces or despotic regimes throughout history.

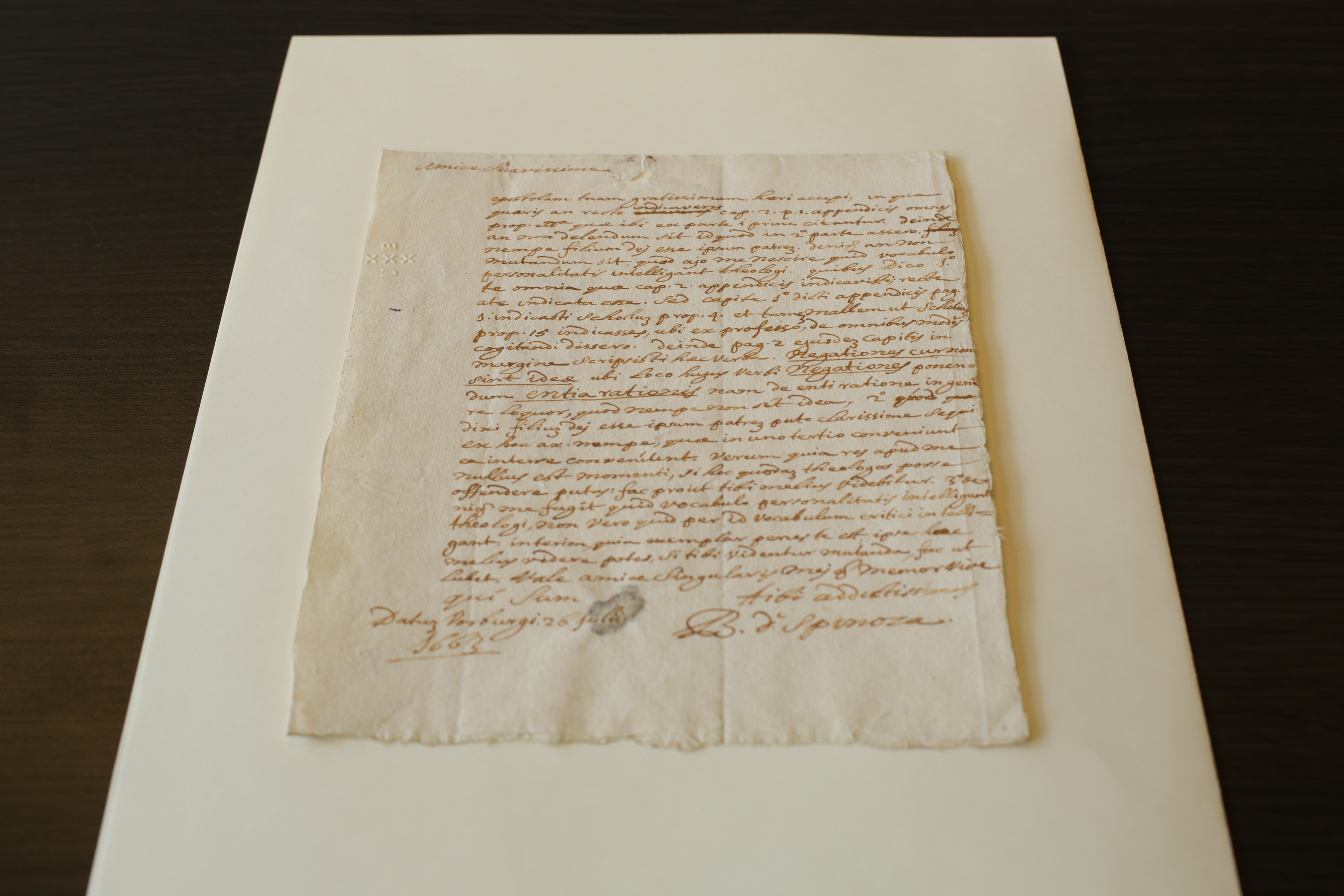

A letter from Spinoza to his editor, property of Special Collections, University of Amsterdam Library. Film still from Pulp: A short biography of the banished book, 2014-2024

A letter from Spinoza to his editor, property of Special Collections, University of Amsterdam Library. Film still from Pulp: A short biography of the banished book, 2014-2024

Erstwhile Czechoslovakia has suffered more than most. In the last century alone, it was first under Nazi occupation and then a Soviet one, and so the brutal destruction of culture under the jackboot would give way to another brutal Communist repression. Prague’s writers and dissidents would resist both invaders and regimes. Notably, when under the Soviet heel, they would enact a form of ‘as if’, taking the illogic of communist diktats at face value, following them to their absurd conclusions. As ironic acts of non-violent civil action, it would constantly infuriate the police, party officials, and bureaucrats in their implementation of repressive laws. The Czechs also kept up an almost-constant supply of underground clandestine printed matter, whether tracts written by local writers and dissidents, or translations of proscribed books, both Czech and international.1 Samizdat texts were a feature across the Soviet bloc and occupied nations behind the Iron Curtain for the duration of the Cold War, despite the ever-present danger of apprehension, detention, harsh punishment in gulags, or defenestration (the latter being a Czech speciality). Sometimes hand copied or typed on illegal typewriters with carbon paper, these texts were even printed at night on party-controlled photocopiers and presses.2 These remarkable, blurry, poorly printed, nondescriptly bound texts of incendiary ideas about freedom and self-determination would become a counter-form of literary output. Early texts in the Soviet Union were not as political, serving as they initially did a more literary and intellectual audience. But with the state crackdown on writers and intellectuals, notably with the charging and convicting of Joseph Brodsky3 in 1963 for the crime of ‘social parasitism’ (for being nothing more socially useful than a poet, and ‘in velveteen trousers’, no less), samizdat became increasingly dissident and political. Soon, the roughness of the samizdat came to be a symbol of anti-state slickly produced colourful propaganda. When the writing, printing, possession and reading of these texts were so harshly proscribed, it was natural that the unassuming, often tattered (from having passed through so many hands) samizdat would be seen as a powerful antidote to state-sponsored dogma.

What the samizdat proves is the necessity of the human yearning for expression, and as an outlet, it serves a non-political purpose as well. Writers need to have their work read, intellectuals need debate and discourse, and when speech is dangerous because anyone could be an informer, the anonymous tract, pamphlet and text will do. Vladimir Bukovsky, Soviet dissident, writer and activist described the necessity and self-determinism at the heart of the samizdat as, ‘I myself create it, edit it, censor it, publish it, distribute it, and get imprisoned for it’.

100-year old survivors of the Leuven University burning. Film still from Pulp: A Short Biography of the Banished Book, 2014-2024

100-year old survivors of the Leuven University burning. Film still from Pulp: A Short Biography of the Banished Book, 2014-2024

This is why the final word on resistance must be given to the form that has consistently proven to be a very effective long-term counter to violence and brutality. Pacifism is a lofty, perhaps naïve, ideal, but it is a state to which our species urgently and collectively needs to evolve. Pacifism, still regarded by many to be analogous to cowardice. While there are still forces of repression, tyranny and violence to counter, we are told that there is no time for pacifism. But this is why the freedom to write, to read, to create and communicate is essential – because we will never make time for pacifism, but we will always know how to make culture. And while this is where we will make our mistakes, it is also where we learn from them, reread and debate them, and pass on the accretion of knowledge, principles, and empathy. It is in our books and music, our art and our inventions that we have denied mortality and oblivion, forgetting and entropy, most effectively. In reclaiming pacifism as an act of courage, it needs to be acknowledged that it is in the making of culture that we also make our stand.

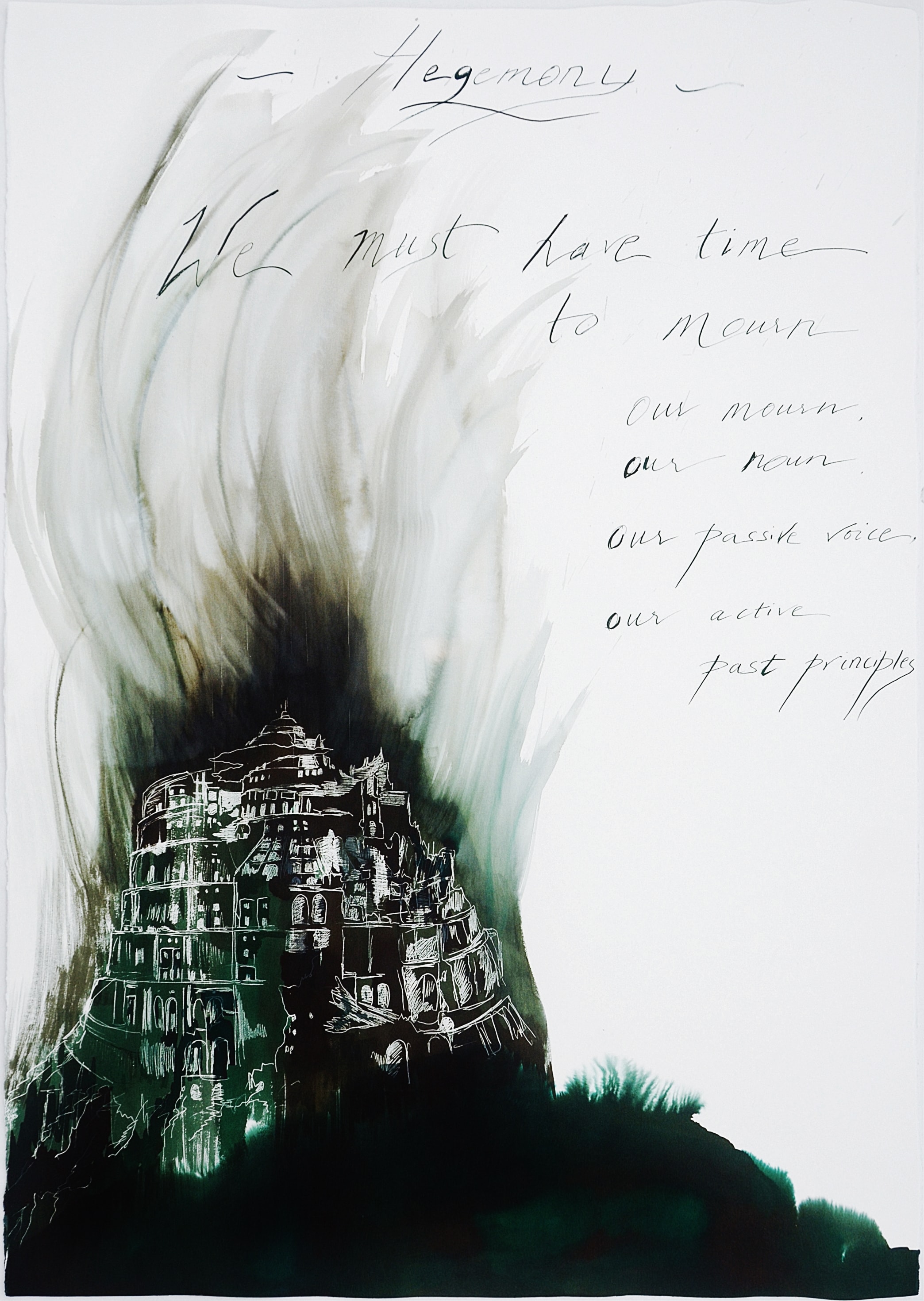

Hegemony, Mixed media on Tiepolo paper, 70×100 cm

Hegemony, Mixed media on Tiepolo paper, 70×100 cm

Shubigi Rao in conversation with Souradeep Roy