Chandan Gowda is a tall, tall man. He is so soft-spoken that his manner of speaking is almost antithetical to his imposing frame. For those who meet him for the first time, it is quite a balance.

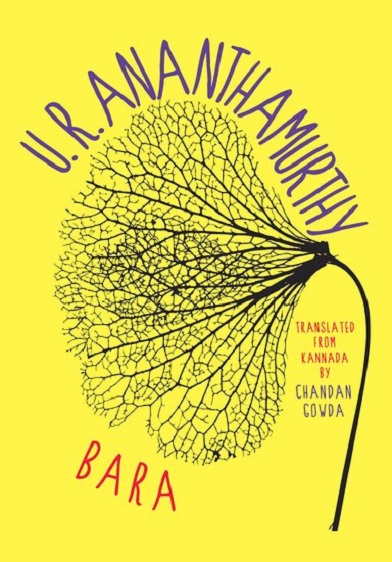

He was in Delhi for a discussion on his edited book The Gauri Lankesh Reader. He is also the editor and translator of Ananthamurthy’s novella Bara, which first appeared in 1976, and was later included in a collection of short stories, Akaasha mattu Bekku (The Sky and the Cat) in 1983. Ananthamurthy, however, had wanted Bara to be published as a book. ‘I had visualised it as a story that can stand on its own’, he writes in the Author’s Note to the book. The story found such a life in Gowda’s translation.

Photograph of The Way I See It / Image courtesy Newsclick

Photograph of The Way I See It / Image courtesy Newsclick

‘Can we go some place quieter?’ Gowda asked. We were sitting in the cafe at Goethe Institute, which was then hosting the City Scripts Festival, organised by the Indian Institute of Human Settlements. We moved to a quiet room.

‘How was the process of working alongside Ananthamurthy? I presume he was looking at the drafts quite closely?’ I asked.

‘Oh, not just drafts of the translation. If you were working on anything and needed his help, he responded with remarkable attentiveness.’

‘But was the translation of Bara the result of an interest in including this story in the body of already established English translations of Ananthamurthy’s novels? I ask this because he was usually sceptical about the narration of an Indian experience in English.’

‘I share the scepticism’, was Gowda’s prompt response. He continued, ‘My translation is not prompted by a commitment to Indian writing in English.’ He paused, as if wondering if he should say this. ‘You see, I wanted to be a writer, and, at some point, I realised this was impossible if I wrote in English. Writing fiction seemed like a hard thing to pull off aesthetically. The sensibility would just not carry. Maybe you could carry it over if you had great imagination. Non-fiction seemed something that I could work with, while poetry was something that I thought was simply impossible.’

In the novella, Gowda italicises interior monologues of the protagonist. I wondered if this was prompted by this sense of impossibility. The dramatisation of this interiority is more difficult than a simple narration of events. The interior movement of the story itself is one of the most significant aspects of the book, especially because this was Ananthamurthy’s response to an overtly political event — the state of Emergency in India declared by Indira Gandhi in 1975.

The Communist Party of India (CPI) had supported the Emergency. Ananthamurthy was, at the time, staying with an idealistic Indian Administrative Service (IAS) officer who had graduated from Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU). He believed that the CPI was right to work with the Congress, which Ananthamurthy calls ‘a national bourgeois party’. The officer wanted to declare the district he was looking after drought-affected, but the Chief Minister of the state postponed this. ‘The officer was caught in a dilemma,’ writes Ananthamurthy, ‘I thought there was great material here for a very realistic story which could take on a metaphorical character.’

II

When Chandan Gowda’s translation came out in 2016, the reviewers were divided on their opinion of the book. Some called it obsolete; others, a relevant book. Reviewers compared the Emergency which triggered the story and the contemporary political climate (which, many commentators argue, is an undeclared Emergency). Both these judgements are, in my opinion, ill-founded because they compare social situations that lie outside the novella. The novella, I argue, is indeed responding to a particular political situation, but its significance or relevance cannot be judged by referents in real life, or by actual political situations, whether it is the Emergency or the National Democratic Alliance government that came to power in 2014. Several reviews, for instance, have referred to a scene between Govindappa, part of a cow protection campaign, and Satisha. It is tempting to think of Govindappa as a modern day gau rakshak, but such comparisons rule out any nuance, and mistake fiction for reality. In his interview with Gowda, published in Bara, Ananthamurthy says that he is ‘sympathetic’ to Govindappa. ‘In my story, he looks funny to Satisha, but he has a point of view’, says Ananthamurthy. These comments seem confusing if Govindappa is mistaken for a real life character. But Ananthamurthy is referring to his importance within the scheme of the novel. The Emergency, too, might have been the immediate political situation that provoked Ananthamurthy to write, but the contradictions between the classes explored in the novel are universal. No wonder he told Gowda, ‘Nothing is out of date for a writer.’

The novella is like a traditional realist novel, with a third person narrator. But the realist details of the characters are not narrated for the sake of those details, as it normally is in a naturalist novel. My reading of a specific moment in Bara will highlight that it employs ‘socialist realism’ because it emphasises ‘hidden or underlying forces or movements, which simple naturalistic observation could not pick up but which is the whole purpose of realism to discover and express’ (Raymond Williams, ‘Realism’ in Keywords, 201). To quote Ananthamurthy’s own words in his Author’s Note, ‘Reality can be grasped only when we go beyond reality in metaphorical ways of exploration.’

U R Ananthamurthy, illustration Mayangalambam Dinesh / Image courtesy Tehelka

U R Ananthamurthy, illustration Mayangalambam Dinesh / Image courtesy Tehelka

Take, for instance, the way in which Ananthamurthy describes Satisha and his father in Bara: ‘Satisha’s father had been pleased to see how they lived. His own lifestyle had cut him loose from his roots; only modernity stuck to him like a parasite. But he was content that his son had a stake in the process of a traditional society becoming modern.’

Even though the narrator here seems to be congratulating Satisha, it is actually a parody of the elite classes and castes. Preceding the section quoted above is an important detail: Satisha and his wife, Rekha, send their son, Rahul, to a common government school. In a letter to Satisha’s parents in Delhi, the couple writes that Rahul has picked up ‘crude language’ and has ‘caught lice’ in his school. ‘This enchanted Satisha and Rekha’s stature in influential social circles in Delhi.’ It is not too hard for readers to understand that Satisha’s praise for his son is actually Ananthamurthy’s bitter criticism for these ‘influential social circles in Delhi’. Rahul’s body has to bear the burden of the anxieties of not just his own parents but an entire social circle. He has to pick up crude language and have lice in his hair to validate the anxieties of an influential class. The novella also ends with Rahul caught in the middle of a communal flare up when he is returning from the ‘common government school’. The novella shows that at the end of the day, the person who has to undergo the violence of unlearning privilege in a privileged structure, is always the most underprivileged within that structure. In the structure of the families of an elite social class in Delhi, this is Rahul. In another structure, Rahul is the privileged being. His story is, at least, narrated because he is born into a privileged class and caste. In spite of his parent’s constant anxiety about making their son a part of the ‘commons,’ he stands out because he is born into a higher social class. His classmates in the ‘common government school’ are not even worthy of narration. This is how graded inequalities are marked in the novella.

III

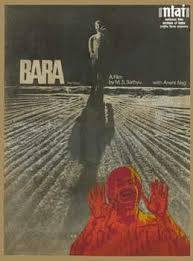

A poster of the film / Image courtesy M S Sathyu’s Facebook page

A poster of the film / Image courtesy M S Sathyu’s Facebook page

The plot of the novella moves through a crisis, and much of the interest in the story is kept alive through a dramatic turn of events. It is not a surprise that the novella has been adapted into two films – both by M S Sathyu, as Bara (1980) in Kannada and as Sookha (1983) in Hindi.

The swift movement in the world outside is supplanted and slowed down by an equally significant movement inward to reveal the psyche of the protagonist Satisha, and his slowly deteriorating relationship with his wife. Here, Ananthamurthy uses interior monologue, which Gowda italicises in the English translation. This section describes a moment Satisha shares with his wife when he is planning to quit the administrative services.

Rekha sidled up to Satisha like a cat and stood with her back to him. Unbuttoning her blouse mechanically, he glanced at his dust-laden artwork from over twenty years ago. The forms he had once viewed as novel now seemed mediocre. No, I was never free from convention and fully alert to everything I saw when I wandered the plains. Rekha pressed Satisha’s hands which rested on her shoulders and turned. She caressed her cheek with her eyes half-closed. ‘Sathi, I love you.’

Wondering if this was a skill learnt at Miranda House to soothe a weary husband, Satisha looked into her dramatically half-closed eyes. They were brimming with tears.

Both the usual markers for thinking interiority are present here: the domestic room and a conjugal relationship. Formally, Ananthamurthy slips into an interior monologue to depict Satisha’s psyche. But, the more revealing moments of Satisha’s interiority occur when Ananthamurthy uses Satisha’s point of view to describe the world outside. The next paragraph communicates the intensity of the tragedy:

‘I’ll be back.’ Satisha went to the balcony. A mournfully silent plain lay in the moonlight: a parched earth, dry trees, a barren rocky land turning into dust, children and women sleeping on hungry stomachs inside their huts, dejected farmers pawning their ploughs. Satisha felt disgusted when he saw how trivial his disappointment was in comparison. I must tear up the application. It is only decent that I do my duty within constraints like everyone else. I’m being fussy only because my pride and self-respect are hurt. He wished something would rise up from the plain and slap him hard.

Satisha’s active gaze takes us to the world outside. The ‘parched earth, dry trees’ and the other things he notices in the moonlight create a mood. What Satisha sees reflects his inner turmoil better than the interior monologues or the scenes of his domestic life.

When I asked Gowda how he knew if the translation was working, he referred to the beginning of the same section quoted above:

There is a scene in Bara where the protagonist Satisha goes to his room, and he is feeling an inner desolation. He is dwelling on one object after another. Something of that slow, deliberate movement had to be conveyed; a sense of that desolation had to be conveyed in English. So I couldn’t speed up the language. He is looking at the plains outside in the dark and he is wondering why people are looking like that. Why would they ever choose to settle down at a place which is drought-prone. There’s no water, not much food; but people have been there for centuries. He can’t understand their choice of settlement. And that is not a means of chastising the people, but chastising himself for being unable to imagine forms of living and dwelling. There is a certain dryness of feeling – that had to be conveyed, somehow. I don’t know if I have succeeded or not.

Gowda certainly succeeds, for the most part, because the mood of the original is carried over in the translation. Ananthamurthy was obsessed with the inner world, which he often called the spiritual world, and, at the same time, he was equally concerned with the world outside. When Satisha stares at the plains, the large chasm between both these worlds makes for the tragic situation in the novella. Ananthamurthy says in his interview with Gowda, ‘My hero is an idealistic Marxist person who is trying to find a space for a spiritual element also (sic). This is what interests me in the young people who are Marxist, but who have a spiritual craving also (sic).’

The drought in the village enters Satisha’s inner being, but could this mood be carried into the translation? Gowda answers, ‘It’s really difficult. At some level, I won’t say it is a way of self-deception. I think there is a certain optimal level you want to keep up, and once you have passed the test of proximity, you know your task is complete. Semantically, you can avoid the usual choice of words: syntax, certain slangs, neologisms…’ ‘Which will wrench it away from the original?’ I interrupted. Gowda’s answer takes me by surprise. ‘The whole thing has been wrenched away, really. But within that practice you are trying to make it a less violent act, make less violent choices.’

Chandan Gowda / Image courtesy Jaipur Literature Festival

Chandan Gowda / Image courtesy Jaipur Literature Festival

Gowda’s answers made me think that he, too, might have felt as much conflict as Satisha, feeling that parts of the translation were barren. In an interview with the Malayali poet and translator Koyamparabath Satchidanandan, Gowda says, ‘Although set in North Karnataka, Bara does not bring in the very distinct Kannada found in that region. The translation, I felt, had to sound like the original. I would read aloud the translated sentences and check if they sounded like the original in their semantic proximity and syntactical effects. I had read out the translation to URA over an afternoon.’

In the Translator’s Note, he writes of his time spent with Ananthamurthy: ‘I interviewed him when he was not feeling well. In fact, he [would] check the interview transcript between dialysis sessions at the hospital. The entire experience [was] moving.’

Gowda’s task may have well been like Satisha’s. But unlike him, Gowda has brought some rain to the drought stricken land.