As a theory of resistance to hegemonic standardisation that diminishes local differentiation, ‘regional modernism’ has been a relevant framework to historicise disparate artistic activities submerged in regional paradigms of cultures, languages and trans-migrating population of folk contemporary artists, etc., in India. We need to also consider that regional modernist arguments have also gained some negative dimensions in the forms of parochial attitudes like anti-urbanism, local exceptionalism, claims against cosmopolitanism, etc. Such dimensions seem to push any such scholarship to yet another, second-order standardising structure. Do the regional-modernist enquiries stem from merely academic premises and end at the same disciplinarian limits? How and where can we locate the political moments that push such enquiries about an art practice of a region? This essay is my attempt to locate certain landmark points of departure in the shifting status of a region called Kerala, as a possible location for regional modernist arguments. The artistic scenario of twentieth century Kerala is not yet well addressed by any sustainable methodology, unlike the case of Madras art movement that is often analysed as a site of the ‘regional modern’ 1. A national discourse of art history synoptically represented regions as signifiers of all that is traditional and exotic, sometimes even a politically disturbing kind of exile and a longing in the work of migrant people from there. Politicising oneself was the alternative for the regionalised consciousness. The Malayalis started it with their art-student activism in the 1980s. The ‘regional modernity’ of Kerala demands a re-oriented, political rigour in a new context of internationalism in the age of large-scale exhibitions and cultural festivals.

Today, the young generation of art enthusiasts in Kerala has an easy access to a new mixed crowd of Biennial viewers. This has challenged the way art is understood in this region. We also need to look at the way the region is used as a token in new practices. We need to look at the way the regional artists and art institutions cannot easily participate in this process of change. In a surge of internationalist, artistic propaganda, there is an impression that the whole of twentieth century art history from a regional perspective is meager and no longer valid. My point is that an art history articulating the power-plays among the multiple registers of acknowledgements is necessary instead of a mere story of a (marginalised) region.

The Frameworks of ‘Indian Art’

First of all, let me very briefly mention the methods we have often used to make sense of a Modern Indian art history. Many attempts were made to historically locate modern Indian art in the twentieth century. These include a chunk of materials like newspaper articles, informed academic articles, curated exhibitions, catalogues, artist-group manifestos, artist monographs, institutional biographies of major academic centers like Baroda and Cholamandal, a few anthologies of Indian Art like the ‘Fifty years of Indian art’, the conference proceedings of the Mohile Parikh Center, Mumbai 1997. And to suggest a few significant collections of critical perspectives, there are anthologies like ‘Towards a New Art History’ and ‘Articulating Resistance: Art and Activism’ 2.

Institutions are powerful in creating artistic tastes. Survey of the traditional past to historicise disparate sources of art in modern times; formation of pedagogic devices; and the generating of individual artist icons are the three major methods undertaken by institutions to make sense of Indian Art in the twentieth century. Surveys of the past often focus on the historical and on the aestheticised object. Right in 1948, such objects of Indian Art had emerged as a field of choice for the self-representation of the nation 3. Art schools in Shantiniketan, Baroda and Madras have devised their own frameworks that organically evolved from specific historical moments, and they continue to play a major role in creating a sense of Modern Indian Art History. Interestingly, all these institutional cases inculcated a profound sense of a ‘national experience’ in the students by drawing their attention to the life of local people, small-town and village activities and the enduring traditions of craft surrounding these institutions. So, a closer observation and study, even the copying of forms and figures of both the traditional resources; and the direct, lived moment formed the ideational epicenters of modern Indian institutions of art vis-à-vis their locations. These were the mainstream methods that infused the indirect linguistic signification of ‘roots’ with the semiotics of a wider national culture 4.

Perhaps because of these varied institutional pressures, Indianness was also a strong point of reference for the making of an artist in India, whether he is an aesthetic idealist, narrative muralist or an artist who has turned into an icon. But throughout twentieth century, this artist-individual has had to inevitably respond to critique or legitimise his subjectivity vis-à-vis some western points of reference 5. The twentieth century Indian artists generally looked like political idealists, deliberating on their national roots and uniqueness. The Indianness devised by the Bombay Progressives, for example, reflected their need for an individual’s modern maneuvers to cater to the modern art market, initiated here by western auctioneers, which often fetishised these so-called modern objects of art. But artists like M. F. Hussain, F. N. Souza and Tyeb Mehta also emerged as the ‘rebellious contenders’. Later, Hussain even happened to linger over the Indian public domain as a ghost of all that was secular and modern in the idea of this unified nation, raising questions about the diversity of religions and cultural expressions of the minorities.

In 2001, the ‘Century Art’ exhibition curated by Gita Kapur at the Tate Modern London loudly declared the connections between the metropolis and the creation of art. The role of Mumbai was also getting stamped in this as a powerful metropolitan location of ‘Indian Art’ by that show. While most of the exhibits relating to the major western cities were familiar, majority of the works from Rio, Lagos and Mumbai were being seen in the west for the first time 6.

I am going to take up this point of departure in this essay. The twentieth century Indian artist’s national significance vis-à-vis the Euro-American world also marks her or his transgressions of regional life vis-à-vis the institutional imagination of a national art history. This imagination was, in effect, a problematic and synoptic view that could be criticised for not acknowledging its own impossibility of creating a unified national signification for modern art practices. It would be better to create a national, modern art that would also be a converging space of many methodologies that can deal with the socio-political conditions of life and art in their own terms in any location. Thinking of this possibility will also amount to a critique of the artificial category of a nation-state that politicises its own under-represented geographies and minorities.

Contrary to general prejudice, the world of Modern Indian Art was not tamed by urbanism. Artists and institutions that could claim their agency beyond doubt could also gain a locational and geographical importance in a Euro-American art map, in spite of being smaller cities like Baroda or pastoral villages that contextualise Shantiniketan or a metropolitan city like Mumbai. But the emergence of the city of Mumbai as a melting pot of much that is Indian in Art also involved a new form of exclusive urbanism induced by neo-liberal conditions in India after 1990. Interestingly, the same contenders for representing the historical idea of national art were also understood as the ideological force behind this ‘century city’; there was a co-existence of contradicting elements like the traditional and the modern, the colonial and the local culture, high art and folk art, etc. 7

In the globalising decade of the 90s, the existential angst of the Indian artist was no longer a mere signifier in his art work but it became a force that bolstered her or his ambition to exist as an artist.

Bose Krishnamachari, ‘Exist’ | Image courtesy Kavitha Balakrishnan

Bose Krishnamachari, ‘Exist’ | Image courtesy Kavitha Balakrishnan

As Girish Shahane has observed, most of the Indian artists selected for ‘Century City’ either focussed on the sectarian violence which wracked the city in 1993, or responded to the imagery of popular culture, particularly commercial cinema, or critiqued some or the other aspect of globalised economy. There was no room for artists who had the courage to admit to his lack of convictions. This observation appears in the catalogue of another show called ‘De-Curating Indian Contemporary Artists’ that travelled to many different locations in India including Kochi in 2003. This show was an indirect response by Bose Krishnamachari , an artist from Kerala who migrated to Bombay to study art at the J. J. School of Art, to the curatorial premises of the ‘Century City’. In spite of being a chronicler of Bombay, Bose’s hesitance to take a straightforward, and moral stand in the then globalised scenario, found him no place in the intellectual milieu of ‘Century City’. Hailed as ‘a handmade tribute to the memory of the whole-time worker, the artist’, ‘De-Curation’ reflected his personal journey as a student of art and art history.

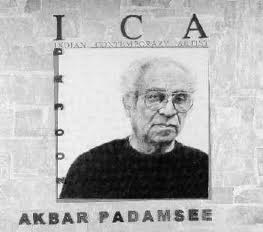

One of the customised portraits of the Indian Contemporary Artist ‘De-Curating’ by Bose Krishnamachari in 2003 | Image courtesy Kavitha Balakrishnan

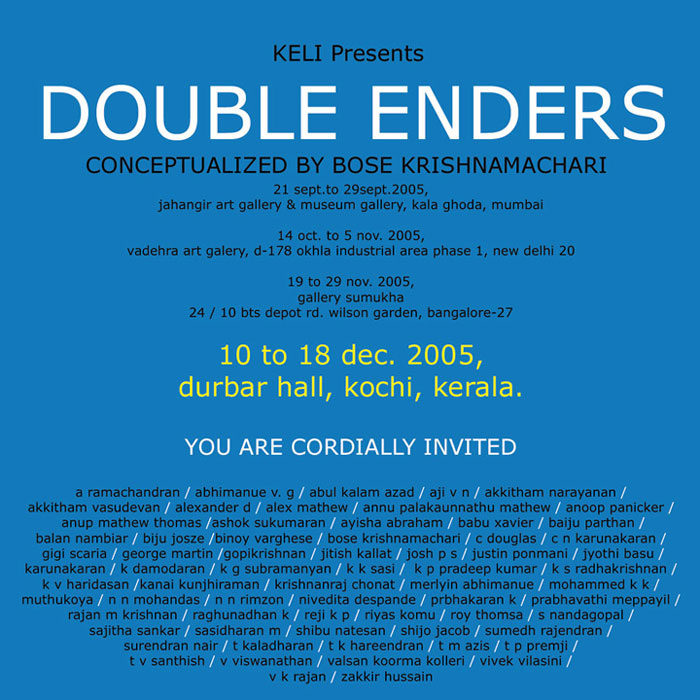

Bose in ‘De-Curation’ proposed a neutral treatment by fashioning Indian contemporary artists he chose to paint as photographs. As Shahane observes, this itself was a kind of statement, resonating in its particular context, the need for an artist to exist in spite of his doubts about the moral stand in an Indian context vis-à-vis the globalised world. Bose was apparently not taking an outright regional stand then, but in the next two years he organised a show of artists with Malayali origins called ‘Double Enders’ at the Kerala Lalithkala Academy’s Durbar Hall. Perhaps like any artist who cannot (or is not entitled to) take a stand in the national intellectual debate, the regions were also considered insignificant and hence marginalised due to their ambivalence about the idea of the nation. Regions often live in distinct ‘other language spaces’ that a national idea could only dub into traditions and tensions. The regions also had ambivalence because they needed to somehow exist within a larger idea.

The Show Invite, Durbar Hall Kochi, 2005 | Image courtesy Kavitha Balakrishnan

This existential angst had already surfaced in the mid-eighties through the activism of radical groups that comprised students of art, of Malayali painters and sculptors. They were in conflict with the mainstream intellectual sphere. Many untold stories of migrations from various corners of India had strong underpinnings of that brief period of radical activism and reached the institutional spaces of Indian Art even though it could not acquire a strong institutional base.

The Political Voices from the Regions

It is in such a context that regional modernism turns up as an argument with respect to the positioning of artistic practices, art works, artists and their lineages that are more or less marginalised during the making of a national history of ‘Indian Art’. The regional resources were largely ignored despite their significance for a national art history 8.

Migrations of young people from the regions to the Indian city centres and academic art centres in search of the life of an artist happened because they found their region inadequate for achieving the life of an artist. They are enthused by what’s out there.

Let me quote the contemporary artist late Rajan Krishnan from a catalogue note written for his final year exhibition at the Government College of Fine Arts, Thrissur, Specimen’37 in 2008.

I wished standing in front of a Cezanne painting that we too needed a painter like him. We needed a lot of artists who could inspire us, sometimes lead us. A Rembrandt, a Bruguel, a Vermeer, a Van Gogh, a Beckman, a Goya, an El Greco, a Picasso, a Dali, a Magritte, a Matisse, a Giacometti, a Pollock, a Kiefer, a Bacon, a Ritcher and there are many hundreds of them, but all in the west.

When such a feeling of lack is part of one’s historical consciousness, it can be due to the absence of links, homes, a childhood; and even the inability to capture the present moment by favouring an imaginary future and an ahistoric past. One feels this lack when one leaves something but captures it in a way as though it was ‘found’ from another point. Such a self-reflexive experience involves an ‘other-ing’ in and out of one’s location — a state of migration in essence. It could also produce an itinerant being 9.

Rajan Krishnan, from the ‘Wing’ series | Image courtesy Kavitha Balakrishnan

During the 1980s, the generation of art aspirants from Kerala who were accessing art education during the transitional phase of a regional institution ( The Government College of Fine Arts, Trivandrum, Kerala) started shattering the illusion of what is ‘out there’ in the world of modern art by gaining exposure to the international scenario through books and journals. Fatal bureaucratic obstacles in a regional art college only increased their desire further for accessing art that veered in a different direction, evident in the art-student activism that led to hunger strikes, street campaigns, and poster-making to raise the local public conscience for art. During the 60s, the reason behind abandoning one’s lesser territory (one’s place of birth, where one grew up, spent one’s childhood and teenage years) was mostly vocational. During the 80s, it was a result of an intellectual imagination that came from their social standing and class consciousness. They wanted to escape from the archaic distortions of the rhetoric of Indianness that they received in the Madras school brand of modernism. During this transitional phase, there were teachers in Trivandrum with the Madras school orientation. Moreover, they wanted to leave in order to resort to the imagination of a fraternity of artists to find an accessible social space vis-a-vis the institutional spaces that alienated them.

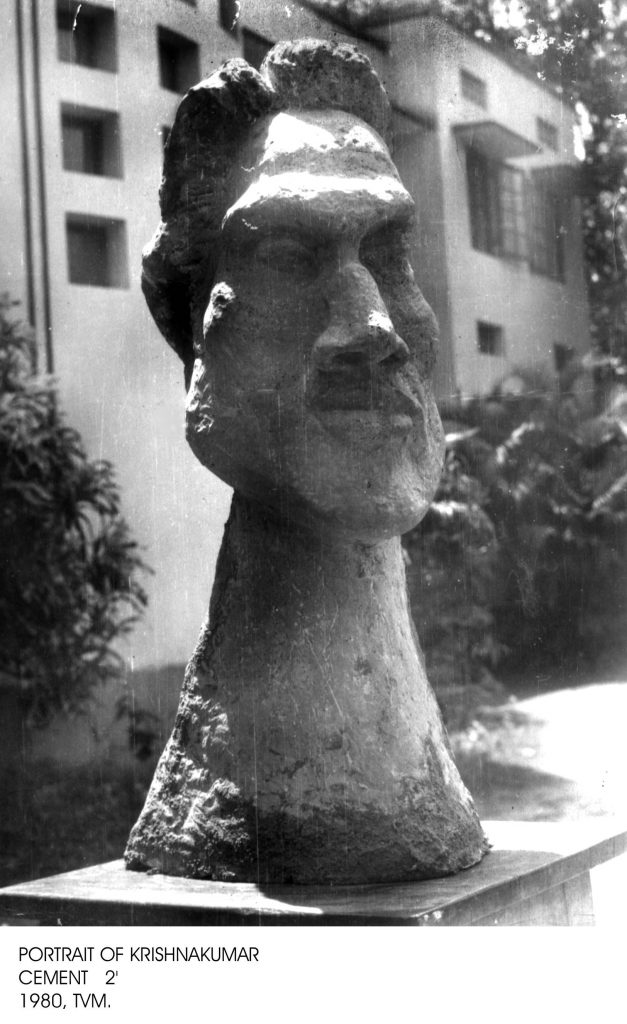

Alex Mathew, ‘Portrait of Krishnakumar’, cement, 1980 | Image courtesy Alex Mathew

These young artists could only communicate with, and were inspired by, the Malayali intelligentsia driven by Marxist ideologies. This radial group’s critique of the institutionalising of art and history was short-lived; and they also lacked resources and sustainable energy.

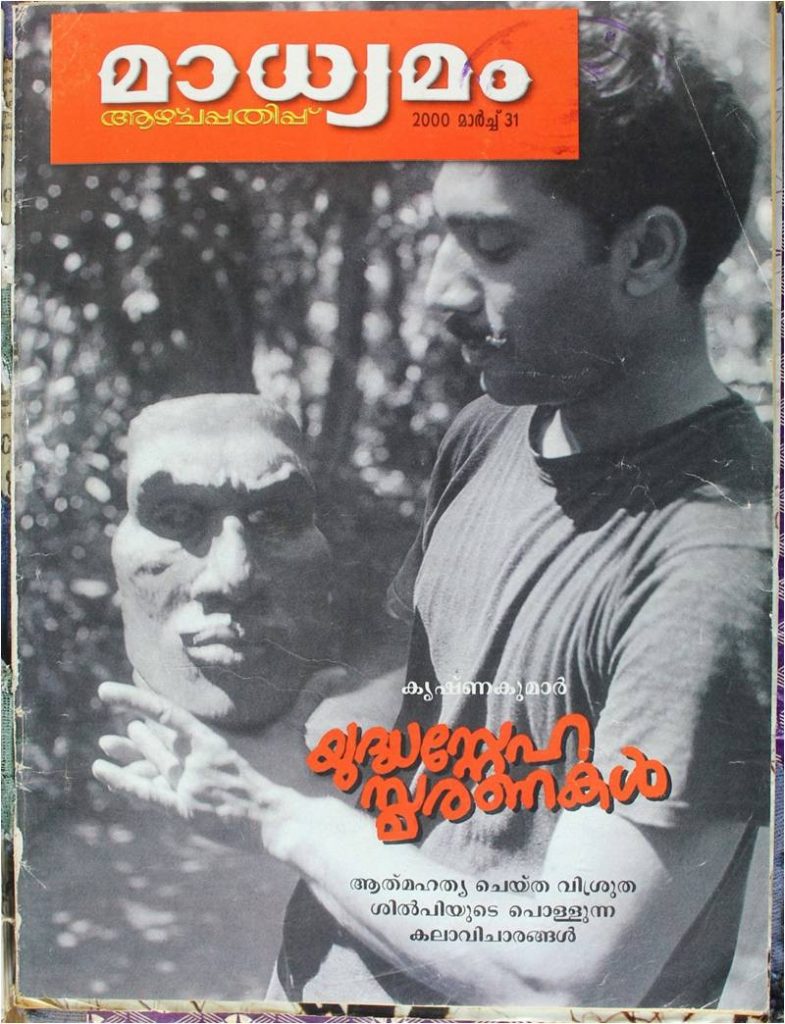

Sculptor Krishnakumar was the main mobilising force behind the radical group. Or, one may speculate that his suicide projected the intensity of a layered ideology gathered from a regional source like the Malayalam literary, political and intellectual circles that were not an active part of any national imagination of art at that time. The group was pulsating with personal, as well as political feelings of lack. The group’s activities were perhaps attempts at romancing (because it emerged out of a sense of lack) with the other histories of art, as well as with one’s own regional working class, finding the only space where the group communicated authentically.

Picture of the cover story on sculptor Krishnakumar in Madhyamam Weekly in 2003 to revisit the historic moment of the radical group | Image Courtesy Saju Kunjan

A post-globalisation world at the dawn of the twenty first century gives a picture that renders the very idea of a ‘national history of art’ unstable. This is exactly where Bose enters with his strategic ambivalence and an absolutism of artist as ‘a whole time worker’, not somebody who is remembered for committing suicide but wins a space for himself by ‘producing work’. The art market driven by the late capitalist economy deployed smarter strategies for adaptation and was more inclusive than any rhetoric of national art. The art market had already picked up from many ‘exotic’ stuff and random locations whether the source is mainstream or regionalised. This defies the logic of the center and the periphery that sustained the need for a regional modernism for long. In the changing scenario of the global art world of the late 1990s, local was also global, overlooking the very category of the national. This also hints at a need to re-locate the political importance of the ‘region’ towards an internationalist turn. It doesn’t happen in many Indian regions, but when it does, it proposes a new problematic for the regional modern arguments.

For example, let me cite the discovery of Gopikrishna from Thiruvananthapuram as a contemporary artist:

Indian art circles discovered him around 2000. Once discovered, in several shows throughout the last decade it was proven that he is a repository of experience who had been undermined and ignored until then due to our attempts at modenising through colonial, and later secular modern, and post-independent patchworks. Gopikrishna re-captures the style of the post-Ravi Varma school of regional painters in Trivandrum, undocumented in any art history yet. Gopi’s father and friends in that generation were among them — dedicated artists who painted royal curtains called rangapadam. Though their technique was foreign, art for them was a matter of devotion and commitment to a royal patronage that disintegrated in front of them, leaving them behind for a mere existence as orphaned artists in an alien system. Overlooking the very category of the national imagination in Gopikrishna’s oeuvre, the idea and bodies of the locale that were once ethnographic docu-materials in a colonial context, now get the life of another idiom coming to us from a forgotten location, just like myths which were produced and carried through moral convictions. But the whole thing could be looked at differently by an urbanised Indian art viewer. I remember visiting the show ‘Exile and Longing’, a group of Malayali artists showing up at the gallery Lakeeren, Mumbai in 2000 when the noted curator Arshya Lokhandwala so excitedly mentioned how ‘exotic’ Gopikrishna’s works looked. And ‘exotic’ was exactly the word used at that moment to refer to an artist who, it seemed, came from a dark and surreal continent of anthropomorphic beings.

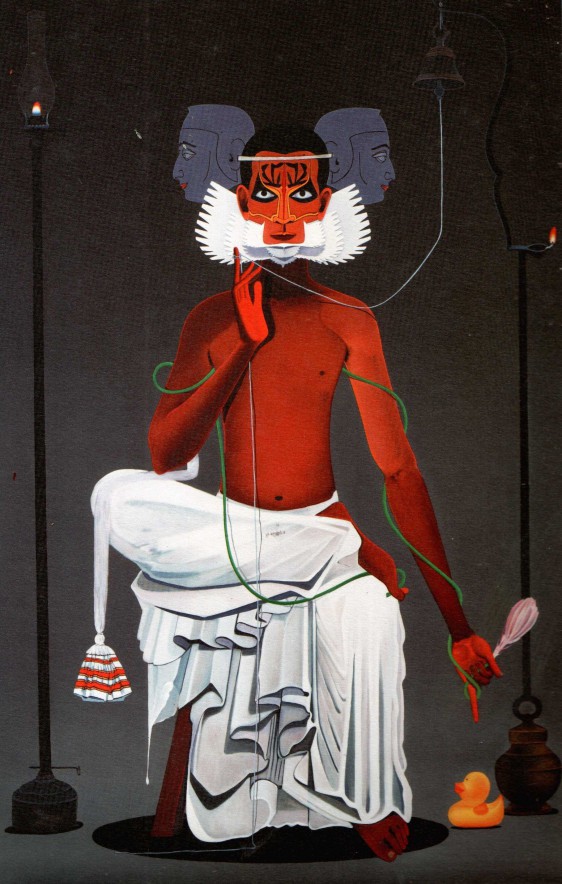

Let me also briefly touch upon another artist whose work also marked a break in the modern national context. Contemporary artist Surendran Nair’s iconic specters bring forth a peculiar regional citizenry, a hybrid folk. They catch the ‘cosmic man’ syndrome. It is also a difficult ‘trickster act’ that breaks in, just as the unconscious does, to trip up the rational (precisely not singularly national) situation. This is more relevant because these Indian folk elements were for long abbreviated as strange expressive motifs just signifying the ideal of a secular Indian nation. They are now so complexly mixed up with the homogenising religious majoritarianism in India’s public domain.

Surendran Nair, ‘Doctrine of the forest — an actor at play’, 2007 | Image courtesy Kavitha Balakrishnan

Again, these are artists who symptomatically represent their historical moment as incoherent beings in an era of internationalism that controls their existence as regional and national citizens.

The ‘Double’ People

Here one can get back to the trajectory of an artist like Bose Krishnamachari who was instrumental in organising a Malayali art work force. His shows like ‘De-Curating Indian Contemporary Art’ (2003), ‘Bombay Boys’ (2003) and ‘Double Enders’ (2005) were landmarks in establishing the lingua franca of contemporary art especially for an art community based in or geared towards Kochi. An interesting fact he deployed in ‘Double enders’ is that simply by the creation of the region as a center, as a pivot, need not always be a parochial issue if it also simultaneously makes its basics right for an institutional practice.

In the current decade, we see the careers and works of many noted artists of Malayali origin who have mobilised with Bose. Some of them have been divided between two locations and two experiences in their lives while some were more comfortable ‘Bombay Boys’, typical expatriates from the regional state who found that Bombay made them alert and dexterous which in turn made one a ‘problem solver’ while the regions were dark mysterious spaces full of history and grandiose associations. This is a ‘Malayali work force of art’ one may say because they were shedding all rhetoric for patronage of the art market. They merged into the sphere of a comfortable high-profile life of a daily art practitioner who produces art objects demonstrating skills that can be capitalized on for a powerful system. This strategy of neutrality ended up in a political alignment with the late capitalist logic.

Crisis in the System and Search for New Relevance

The global economic crisis altered the tune of this alignment by 2010. From mere existential anxiety, art practice needed a different and stronger reason to sustain itself. Crisis of the system pushed people to address the deep-rooted question: what exactly is the reason behind our rigid institutionalism and as a fall out effect of that, the marginalisation of the other? Modern Indian Art still needed to find its social relevance10. We find that the symptomatic connections for each institutional location and the artist-individual’s iconic languages with the larger idea of the Indian state in the twentieth century were virtually the effect of their relevance in a limited architectonic space of a city or small town.

Initiated by Bose Krishnamachari and Riyas Komu, the first Kochi-Muziris Biennale was branding a second tier Indian city Kochi in terms of its abstractedly conceived cosmopolitan history in an extended Musiriz location which is an ancient trade route. It also took the challenge to arouse the Indian public’s desire for large scale exhibitions. An unrealized effort at the Delhi Triennial was a point of reference. Kerala government was brought into its own and took the responsibility to help develop an artistic context in the region. But the whole project was thrown into the region from some unknown corner. No prior public dialogues with the existing regional institutions for culture and art was initiated. Their agency in this radical shift was totally denied. This really politicised the region’s artistic public who alleged scandals on one hand and put defenses on the other hand. But I believe, this was the most poignant situation created in India’s history of art because it was also generating some significant questions from a regional context, generated primarily from its regionalised condition.

The three editions of the biennales have, so far, created great shock through art and culture in this region, demanding the need for both ‘culture consumers’ and an informed viewership for art. This has raised the need for various tones of art writing in both Malayalam and English. It has also exposed a huge gap in communicating art to an audience which has different orientations. Any discussion of the latter part is beyond the scope of this essay. So, as a regional insider, let me confine myself to certain reflections about this new scenario which can further shed light on the political undercurrents of these changes in the regional experience.

Let me touch upon a few connecting threads of ‘regional modern conditions’, in other words, the marginalising forces still actively working in the Biennale times.

Which art world does one belong to?

Five years back, in a review of our degree shows, written in Art and Deal, I had expressed a few concerns: What are the art worlds and art histories that matter to the art students in front of me? This was what I had in mind as an art history teaching faculty at Government College of Fine Arts, Thrissur, an institution that has a century-long ‘silent past’ in art instruction activities. Art history lessons already give them both ‘Euro-centric’ and ‘nationalist’ legacies of art, and an image of an ambiguous art world is generally conveyed. That does not necessarily impart the right to experience in one’s own vicinities the ‘edgy new’. Unless the art institution is directly situated in a place with developed gallery practices and overcomes bureaucratic obstacles to critically connect with mainstream discourses, an experience of transforming one into the life of an ‘artist’ when one clearly asserts ones agency and authorship, is staved off. When one is left to wait, one is either regionalising oneself or is being regionalised by others.

Atul Dodiya, Bose Krishnamachari and Jyothibasu with the students of the Government College of Fine Arts, Thrissur, May 2010 | Image courtesy Kavitha Balakrishnan

Let me connect this with another instance of the experience of meeting two visiting faculties: In the first instance, Bose Krishnamachari exhorted the students to make a list of world’s ten leading artists, museums and collectors. The students generally showed a resistance and boredom in this googl-ing exercise given as assignment. They seemed to have had in mind the question: ‘Where do I or we picture in this art world?’ The other visiting faculty was a local wood carver Mr. Shankaran, who did not test the students’ artificial belongingness to any strange ‘art world’, but he turned himself into a silent specimen of a carver with tools. More than an artist, Mr. Shankaran was a specimen who might represent an under-represented archaic artist figure possibly found in the mythology of Gopikrishna’s paintings.

Wood carver Shankaran as visiting faculty at the Fine Arts College, Thrissur, with students and teachers | Image courtesy Kavitha Balakrishnan

While the pedagogic practices should clearly articulate such multiple layers of contradicting art practice specimens, what is initiated by the growing biennale institution is a survey-type methodology and a tokenistic attitude. Let me list some instances. The first one is the student biennale. In the second edition, the display of art works curated by a select set of young curators assigned to various Indian regions showed a very irresponsible alignment, without really generating any specific insight into the scenario of Indian art institutions. The second student biennale was an improved and smarter display, but it lacks any art-historical articulation. This exercise only makes the biennale institution an ‘inclusive desirable and representative machinery’ for the young minds.

Student’s Biennale display, 2016 | Image courtesy Kavitha Balakrishnan

Another instance pertains to my own personal differences in perspective related to the intentions of a trend of archival exhibitions in contemporary art. For the first edition of Kochi-Muziris Biennale in 2012, my research and documentation of periodical print-picture practices in Malayalam was further selectively displayed through a collaboration called ‘varavazhi’ initiated by Riyas Komu. An archival show, ‘Re-visiting the print-pictures’ was executed.

Re-curating periodical print pictures by Varavazhi

It looked like a curious archive floating in the gallery, reflecting the missing cultural threads of communication just suggesting that there are some such undercurrents of a discreet visual field of a region like this in contemporary life. The critic’s register was unclear in that show. I was not simply a participant in these regional materials, but by choosing to investigate, write and curate it, I also wanted to expose a male-dominated and thoroughly regionalised field of Indian culture of the twentieth century literate reader-viewer. This was only tested later in a rural art project I had initiated at a place called Mathilakam.

Propaganda of art can create passive spectators as is evident by the increasing number of visitors to Kochi biennale. But, actively informed critical viewership for art is also a result of this. That evokes the need for alternative practices and that alone will directly address the social life of art and artists.

Let me mention one such instance. In the rural art project at Mathilakam, Thrissur district that I initiated as an independent segment in the Chilappathikaram Festival as part of the second edition of Kochi biennale, Abul Kalam Azad, a contemporary photographer based in the temple village of Thiruvannamalai, did a photography project titled ‘Black Mother — Contemporary Heroines’. He documented the contemporary women in Mathilakam village. The language he employed was that of an anthropological gaze towards ‘native women’ that we are quite familiar with. But the process involved a stranger man’s access to the females at their households, breaking a dialogue with them regarding Kannagi, the heroine of Cilappathikaram. The dialogue proved that the contemporary women at this village are, by and large, unaware of this heroine, even though the festival organised by biennale was celebrating the spirit of Kannagi uncritically, as an element of propaganda of a new rhetoric of empowered women. Azad celebrated the heroines of his photographs by displaying them on bill boards in the locality. The families of some ‘contemporary heroines’ were irritated. Though they cooperated with the photographer’s request to be his fancy models for the art project, it was embarrassing for some women to see themselves blown up as real life images. The vinyl displays were soon dismantled to avoid unrest in the village.

Images in the ‘Black Mother’ project | Image courtesy ETP, Thiruvannamalai

The argument of this essay is that the history of art from the perspective of Kerala (or any regionalised location in the twentieth century for that matter) is gaining more importance as a layer among many layers that can make a region in a post-globalisation world, a container of a very complex network of artistic attitudes. We recognise this perhaps not through artistic significations alone, but more through an analysis of the art-public that is created today, especially in such ‘biennale regions’. A new mixed breed of spectators, informed, ill-informed, half-informed and even challengers, are created for the singular establishment and the growth of exhibition institutions like the Biennale. They also grow outside the more exclusive gallery spaces and their stalls in art fairs. This, in effect, touches upon the question, ‘what is the social capital of contemporary art?’ The regional biography of art in Kerala will not be necessarily the same as the art history of a city called Kochi as a biennale location. Like the paradigm of ‘Indian Art’ in the twentieth century, Kochi is a city within and without its region. But the Malayali public experiences belongingness to and alienation from both. There is a pervading sense that any public beyond the borders of nationality can randomly take shape in the name of art. This is a new mode of artistic urbanity possible in a region, and that is under construction. And the question that would arise there would perhaps be, ‘what happens when the archives of the ‘unclaimed modern’ in Modern Indian Art meet the politics of display of the Biennales, cultural festivals and such large scale expositions?’.