It has been an extraordinarily regressive start to the new academic term for Indian institutions this year. The already beleaguered Jawaharlal Nehru University has seen attempts by the campus administration to single out and intimidate individual faculty members for their political views; suspend or dissolve bodies that are supposed to look into sexual harassment complaints; install militaristic symbols of state power like army tanks on the premises; and, most worrying, drastically cut student admissions to MPhil and PhD programs, especially in the humanities and social sciences.

Najeeb Ahmed, a Muslim student who entered the MSc program in Biotechnology last year, disappeared after an altercation with students from a right-wing Hindu student group, a year ago in October 2016. He has not been found, alive or dead, and the authorities have done nothing about it. The Vice Chancellor and the university administration seem to be continually at war with the academic community in their charge. JNU is consistently rated one of India’s top research universities. Why the government is hell-bent on destroying this lively and prestigious institution from within remains a mystery.

The situation at Banaras Hindu University is even more appalling, with the campus authorities there attempting to police and discipline the female student population, fully backed by Chief Minister Yogi Adityananth’s state administration. Every cliché of patriarchy, sexism, social conservatism and majoritarian violence converges upon the hapless women students of BHU. They have fought back with admirable courage, alas to discover that the microcosm of their university is embedded in a larger environment where these backward tendencies are only encouraged and magnified, not resisted.

The assassination of Gauri Lankesh, a brave, outspoken and widely respected journalist, activist and editor of the Gauri Lankesh Patrike, an independent Kannada newspaper, dealt a deadly blow to the already endangered freedom of the press in Modi’s India. But that the target this time – of as yet unidentified killers – was a woman, suggests that the most malign misogynistic and authoritarian tendencies of the Hindu Rashtra are now fully on display. Minorities, dalits, students, people on the left, liberals, artists, intellectuals, journalists, academics, activists and women in public life are equally at risk. If you combine two or more of these categories, then you could well end up disappeared like Najeeb, or murdered like Gauri.

These signs of a continually regressing public sphere are all around us. But recent shows in the capital about art, architecture, urban works and a previous generation of ‘the makers of modern India’, looking at a period from the 1950s to the 1990s, reminds us that we really are in an age of reaction today. ‘Stretched Terrains’, a series of exhibitions at the Kiran Nadar Museum of Art ongoing since February, and ‘Shared Legacies’ at Bikaner House, marking seventy years of Partition and Independence in August, are deeply moving for showing us a very different India, one that we remember as though it were yesterday – and it was – but that is fast eroding and buckling under the onslaught of Hindutva. Some of these exhibitions, particularly the photographic work of both Ram Rahman and Parthiv Shah, spell out exactly what India stands to lose: its very modernity.

***

We are accustomed to thinking about modernity in India as a mixed blessing at best, and an ecological and moral disaster, at worst. Gandhi and Tagore left us with strong criticisms of capitalism, nationalism and technology that form the pillars of modern life; Nehru and Ambedkar, on the other hand, were focused on the developmental, progressive and emancipatory possibilities of modernity. These two strands of critique and aspiration are intertwined in the very DNA of postcolonial India.

But Hindu Nationalism, while pretending to respect ‘tradition’ (parampara), lacks the basic egalitarianism of critical traditionalists, and while pretending to champion ‘development’ (vikaas), shows no awareness of the dangers of unbridled growth in a time of serious planetary crises, both economic and environmental.

Ram Rahman has been collecting and curating the architectural photographs, plans, models and other archival materials of his father, architect Habib Rahman, as well as the group of architects, structural engineers and urban planners who conceived, designed and built much of modern Delhi in Jawaharlal Nehru’s time, from the late 1940s to the mid-1960s, continuing through Indira Gandhi’s time, right into the late 1980s. This extraordinary set of modernists included, besides Rahman’s father, are Raj Rewal, Mahendra Raj, Achyut Kanvinde, Kuldip Singh and J.K. Chowdhury, and the American architect Joseph Stein. (Charles Correa is absent, sadly, as he did not build that much in Delhi).

Rahman often uses photographs by his father, by the legendary Madan Mahatta, as well as his own (contemporary) photographs. Together, these show us the unique vision that gave rise to New Delhi as another layer atop a millennium-long palimpsest that already included a Sultanate city, a Mughal city, a colonial city and Lutyens’ Delhi.

These men created almost the entire institutional architecture of the post-colonial state. Many of them were students of, or in conversation with other modern masters like Le Corbusier, Henri Cartier Bresson, Charles Eames and Walter Gropius, many of who flocked to India attracted by the cosmopolitan, intelligent and elegant personality of Nehru. As the first prime minister, he had set out to build new cities like Chandigarh or rebuild old ones like Ahmedabad. Inevitably these became international undertakings, albeit in an Indian setting.

The national academies of the arts and literature, the IITs and IIMs, central banks and financial institutions, auditoriums, educational and training institutes, offices of public sector companies, government housing, art galleries, memorials, stadiums, exhibition halls – all kinds of massive buildings and important public infrastructure came up in the first three to four decades after Independence, especially in Delhi.

Rahman’s superb curatorial intervention reveals the unmistakable signature of modernism in a variety of structures and sites. Monumental, minimalist, functional, nationalistic, often decorated with gigantic murals and outdoor sculptures, blending traditional materials and construction techniques with twentieth century design and technological innovations, these buildings suggest an idealism which has permeated the work of the two generations of architects and artists, and whose fountainhead was Nehru himself. They shared an energy that only a new nation can experience, perhaps, even if it is created on the plinth of an old civilisation. The sense of open spaces, blue skies and a genuine freedom to experiment comes across clearly, more so in Mahatta’s pictures taken as the projects were first begun or freshly completed.

***

The recent demolition of the Hall of Nations and the Nehru Pavilion at Pragati Maidan, razing the work of architect Raj Rewal and engineer Mahendra Raj, is nothing less than an act of vandalism by the current administration, rudely interrupting an ongoing dispute on the future of these buildings, currently being heard in the courts. Here we see a willful destruction that is equal parts real-estate manipulation, land-grab and ideological violence against what is undoubtedly a symbol of an older, Nehruvian and post-Nehruvian Delhi.

Nehru’s inaugural address to a ‘Seminar on Architecture’, organised at the Lalit Kala Akademi in March 1959, ought to be compulsory reading for all Indian citizens interested in the foundations of their nationhood. In his usual charmingly rambling, carelessly erudite, affably grandiose style, familiar to us from The Discovery of India, Nehru holds forth on past and present, beauty and technology, form and function, history and industry, temples and cathedrals, the Taj Mahal, and most importantly, Chandigarh. He describes Chandigarh as ‘a thing of power coming out of a powerful mind’, that of Le Corbusier.

Nehru closes with these words, so simple and straightforward yet, so hard to imagine being uttered by the leadership today: ‘The main thing today is that a tremendous deal of building is taking place in India and an attempt should be made to give it a right direction and to encourage creative minds to function with a measure of freedom so that new types may come out, new designs, new ideas, and out of that amalgam something new and good will emerge.’ Something new and good – isn’t that what every worthy leader ought to envisage, for India?

Humayun Kabir, who was interestingly Minister for both Scientific Research and Cultural Affairs, said in his welcome address that he hoped that the architects present at the seminar would use the discussions and debates ‘to be able to supply the requirements of a new India, a free India, a democratic India which is aiming to be a Welfare State, an India which is aiming at reconciling differences and combining them into a unity.’

Rahman has extensively documented the structures of Pragati Madan, in photographs and videos that are now as breathtaking as they are heart-rending, given that key sections of this iconic campus have been demolished despite a stiff legal challenge put up by city planners, urban historians and other stake-holders. Like the havoc being wreaked at JNU, the flattening of Pragati Maidan is another instance of the BJP government cutting off its nose to spite its face. The very name of Nehru is like a red rag to a bull; the Nehru Memorial Museum and Library too, stands to be repurposed and possibly renamed at any moment. Jawaharlal Nehru and Humayun Kabir addressing a gathering of architects sixty years ago might as well be speaking a foreign language, from the perspective of Modi’s India.

Ostensibly, the trigger for the wrath of the ruling Hindu Right dispensation is the legacy and memory of the Congress party, led more or less without interruption by the Nehru-Gandhis from the 1920s to the present. But if we look deeper, the actual irritant is in fact much more significant – it is modernity itself, as a set of philosophical considerations, reflected in both politics and aesthetics, that gave free India its identity and direction over the past seven decades.

The Hindu Rashtra cannot be modern, plain and simple. It cannot stand the questions that students and youth ask of authority. It cannot stomach the equality and education of women. It cannot accept that western influences inevitably and inescapably colour our cultural life long after decolonisation. It cannot bear the demands of Dalits for dignity; as for Muslims, even their very presence and participation as Indians cannot be tolerated.

***

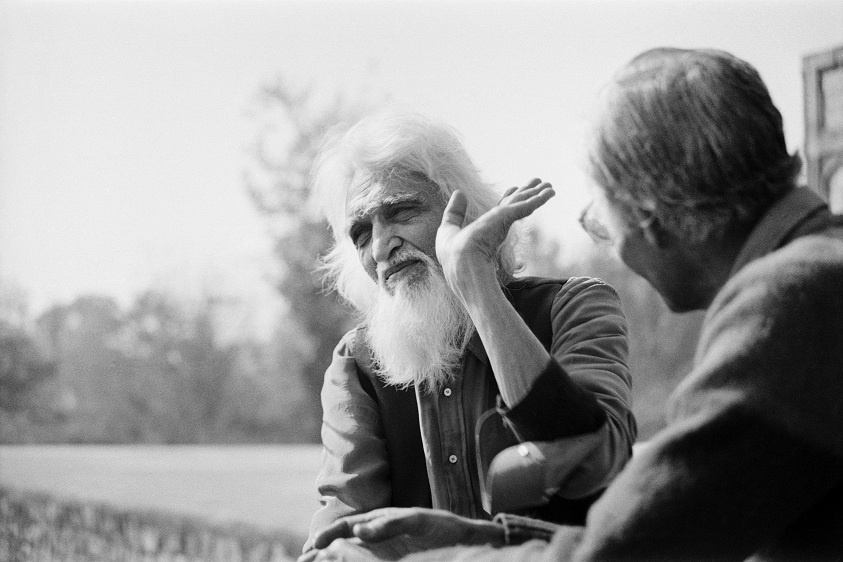

If we allow it, this government will demolish – stealthily, by night, against court orders – the very edifice of our modernity, as it has demolished the Nehru Pavilion at Pragati Maidan. Parthiv Shah’s evocative photographs of the celebrated painter, Maqbool ‘Fida’ Husain (1915-2011), taken in the 1990s in Delhi, capture this endangered spirit of modernity in a very different, but related way. In large format black and white prints, Husain is sensitively photographed wandering about in the alleyways of Nizamuddin Basti, playfully striking poses at the National Gallery of Modern Art, sitting-standing-lying down with his own paintings and art-works, and talking with friends like the progressive artist and abstract painter Ram Kumar at Humayun’s Tomb.

Through Shah’s lens, Husain is tall, white-haired, bearded and barefoot, a striking apparition at any time, but in our dark days, an almost impossible vision of artistic whimsy, free-spirited ease, and unselfconscious belonging in a place and a time.

He’s restless but comfortable – in his skin, in his neighbourhood, among his peers, in India. The camera seems not to intrude in any way.

Image courtesy Parthiv Shah

Image courtesy Parthiv Shah

Shah, who was a very young photographer at the time when these pictures were taken, clearly managed to establish an excellent rapport with Husain, who is completely unselfconscious (except when he is deliberately posing!) There seem to be no impediments to his creativity – he is extraordinary, but, at the same time, unpretentious. You can see in his lanky figure, his shambling gait and his bushy brows a manner of relating to his environment where everything that he sees around him, all the matrices of class, religion, caste and history that he traverses, are almost certainly grist to the mill of his art. He’s a traveller, for sure, but he’s unmistakably at home.

In another part of ‘Shared Terrains’, titled ‘Yatra: The Rooted Nomad’, one could see many of Husain’s own works, and what really jumped out was the dizzying mélange of styles, his calligraphic ease with many different Indian languages and their scripts, and his ear to the ground of rural landscapes. All of India: complex, multifarious, unresolved, lived in Husain’s eye; all of it real, and hard, and soft and wet and dry and clean and dirty under the soles of his bare feet. Full, fearless, joyous contact with India – that was Husain.

The harsh fact that Husain was vilified and subjected to communal abuse; that he spent his last years in Qatar, far from his beloved homeland; that he felt exiled and threatened after being India’s most famous and successful modern painter, all of this only makes Shah’s intimate, unobtrusive portraits the more poignant. I live in Nizamuddin – I moved in barely three months after Husain’s death. The thought of Husain ambling about in the neighborhood, sitting at the Dargah, chatting at the Tomb, drinking chai in the Basti, reading a Hindi newspaper in the winter sunshine, makes my hair stand on end even today, makes the hallowed ground of Hazrat Nizamuddin and Amir Khusro and Mirza Ghalib (and Ashis Nandy) even more sacred, to my mind.

Husain died, aged 95, of a heart attack in a British hospital in June 2011, and is buried in a London cemetery.

Kitna hai bad-naseeb Zafar dafn ke liye,

Do gaz zameen bhi na mil saki koo-e-yaar mein!

***

I spent some time talking to Ram Rahman, Parthiv Shah and the art critic S. Kalidas about these images, on modern Delhi, of Husain in Delhi. All three are the offspring of important figures of an earlier generation – Ram is the son of the architect Habib Rahman and the dancer Indrani Bajpai; Parthiv is the son of the artist Haku Shah; Kalidas the son of the painter J. Swaminathan. Seen though their eyes, the period under question is a matter of both public history and personal memory.

These are literally the children of India’s aesthetic modernism, thanks to their parents, as well as the heady socio-cultural milieu in which they were raised. For them, returning to an earlier period in the life of modern India is both a journey back to their own childhood and youth, but also a form of resistance to the assaults and indignities of our present politics. Shah and Kalidas had a marvelously engaging public conversation at the KNMA on 31 August, introduced by the curator of ‘Stretched Terrains’, Roobina Karode, in which they reminisced about the Indian art-world the way it was when they were growing up. Shah shared many more photographs of well-known artists from his personal collection, taken without any plan or intention to document or exhibit, just naturally, in the course of life itself. Rahman similarly led a panel discussion at the KNMA on 2 September with Raj Rewal, Mahendra Raj, Kuldip Singh and Achyut Kanvinde’s son Sanjay Kanvinde. Intimate knowledge and personal stakes for all the participants enriched both discussions immeasurably, making the past come alive.

Indian modernism – across fields – in literature, in the arts, in architecture and design, in politics too, is one of the great chapters in the history of global ideas in the twentieth century. Like the filmmaker Satyajit Ray’s Apu Trilogy, so beautifully explicated by scholar Geeta Kapur, the modernism of Habib Rahman and M.F. Husain too, holds up a mirror to the nation. Their works suggest a coming of age, a journey, a hybridity, and an inner conflict, all of which belong as much to India itself as to the creative individual negotiating a passage through the modern world, hauling tradition along like a burden or like riches, depending.

It is this capacity to know what is ancient and make what is unprecedented; to be tentative and confident at the same time; to remain planted while yet mobile, to fashion a selfhood such that we can be with ourselves and yet live with others – this is what is under attack today, from the Hindu Right. Something new and good, that we were making, that we are losing. A wall to hang our greatest art; a piece of earth to bury our dead; buildings that belong in our age and reflect our deepest desire for home, our human need for community, our right to privacy.

We have to remain alert, and we have to fight back.