Lady Anandi is a performance about my great grandfather, Madhavrao Tipnis, who was a female impersonator in Marathi theatre in the late nineteenth century. The impetus to create this performance came while I was reading Virginia Woolf’s A Room of One’s Own for a dramatised version of the novel. Woolf writes, ‘To have lived a free life in London in the sixteenth century would have meant for a woman who was poet and playwright a nervous stress and dilemma which might well have killed her. Had she survived, whatever she had written would have been twisted and deformed, issuing from a strained and morbid imagination. And undoubtedly, I thought, looking at the shelf where there are no plays by women, her work would have gone unsigned.’1 As I was grappling with this text, I questioned my place in the theatre, the lines I was told to speak, the characters I was made to play, and the reactions I received when I decided to be a full-time theatre actor at the age of 34. A hard, honest look at these questions revealed that I did not have any agency as an artist. I wanted to create a production that allowed me the freedom to explore; to speak lines that resonated with me; to experiment with forms that questioned the boundaries between performance and research, actor and audience, a finished text and a work in progress.

Personal archives and oral histories have always intrigued me. Prior to my work on Lady Anandi, I completed an oral history project on my grandfather, Ram Tipnis. He was the oldest living make-up artist in India. This time I chose to tell the story of his father, Madhavrao Tipnis. The premise was simple. There would be two actors separated by a hundred years. One would play a lady convincingly, and I would play a character struggling to be a woman on stage. I began searching for archival material on him. I looked online; there was nothing. In theatre-history books he was a mere footnote. My excavation was drawing dust. It was becoming apparent to me that he was absent from theatre history. I looked at family albums. One aunt had three photos, the others a few more. In the few stories I had heard of him while growing up, he seemed like a hero who played both male and female characters with ease, received critical acclaim, drank five litres of milk a day, and loved wrestling. Could these stories feed my nascent imagination? Or was he an apparition? If not, why was he missing from the archives? Since he had died several years before I was born, I had no memory of him. My extended family remembered him as a ‘good man’. How could I negotiate this amnesia? How can we remember the dead when there is little or no record of the deceased person?

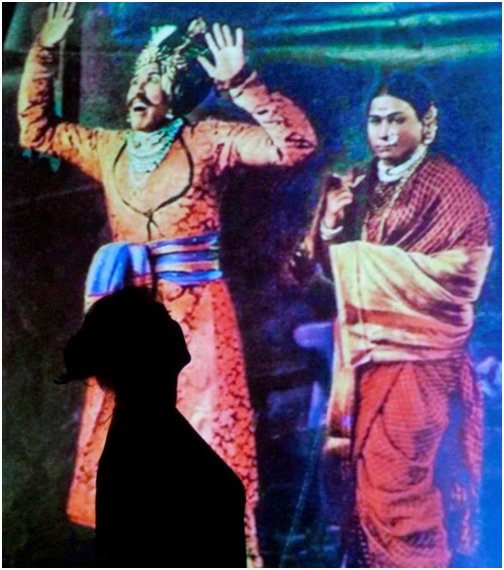

Eventually I found twenty-odd photos of him. With that, I began to identify the plays he had performed in – Baaykanche Band, Kichakvadh, Bhaubandaki, Shah Shivaji, Sangeet Chandragrahan, Manjirao. I found a few scripts in dusty libraries, and one, quite surprisingly, on the website of the Indian Institute of Science. I started sketching his character through the parts he had portrayed. I also read autobiographies of other female impersonators. I began to imagine his character by imagining Madhavrao the person. In the absence of memory that could recreate the life of my great-grandfather, I turned to fiction. Using anecdotes, photos, documents, interviews and reviews, I constructed a performance titled Lady Anandi.

The title is a reference to Anandibai Peshwa, a historical character played by Madhavrao in Bhaubandaki (1909) written by Khrushnaji Prabhakar Khadilkar. Anandibai was infamous for instigating her husband Raghunathrao to murder his younger brother, Narayanrao, in order to usurp the throne. Anandibai intrigued me. She was a lettered woman with a dark thirst for power. She changed an alphabet in a letter, dh cha ma/ from catch to kill, which led to the death of Narayanrao.

I began writing scenes based on the little information available to me. I did not write the scenes chronologically, but as and when I found enough material on Madhavrao Tipnis. The performance had three characters:

Character 1: A male actor in his 60s. He plays Madhavrao and Lady Anandi.

Character 2: A female actor in her late 30s. She plays Lady F – the narrator.

Character 3: Any capable female actor. She plays Indumati – the fan, Yeshwant – the older brother, and Malati – wife of Madhavrao.

I worked with three actors to play the characters described above. It was unfolding like a play with a conventional structure. The actors were learning their lines; I was the writer and director, telling my actors where to stand, how to walk, replicating the process that I had long been part of. But it was this process which itself made me question my agency as an artist. More importantly, while watching the play unfold, I felt there was a missing element — a voice and a body that drew the audience’s attention to the fact that Lady Anandi was an attempt to fill an absence in the archive.

An archival absence is not an accident. The act of reclaiming this absence is also deliberate. Lady Anandi is an act of remembering. Rivka Syd Eisner says, ‘Performing memory is more about bearing witness. Bearing witness, however, does not just entail carrying memory. Bearing the past is allowing it to enter into bodily consciousness and continuing social experience, so that living with memory means giving residence to pieces of the past that in turn, even in their painfulness, sustain and charge one’s own being.’2 I needed an element where ‘bodily consciousness’ and ‘giving residence’ to the past could come to bear on the performance. It was clear I had to be part of the performance not just as the writer or director but also as an actor. I had to embody Lady Anandi. The past would then be mediated through me. I had to make this apparent to the audience. Thus, Lady Anandi became a solo show, where one actor plays all the characters. One review described this choice in this way: ‘This idea of how gender is performed becomes stronger when there is only one person acting, because now that one person is everybody – a woman, a man, a man playing a woman, a young girl, a married woman, an admirer, and a young girl in love with a man who acts as a woman.’3

Constructing Lady Anandi as a solo was the first decision in experimenting with the form of the performance. It was followed by a more radical choice – to read the fictional parts of the performance aloud; memorise the research; and recount it like a story. The act of reading the play could be compared to finding archival documents, only these were fictitious. And recounting research by rote would add to its ‘authenticity’. This enabled me to push the form of my performance. The act of reading the scenes upset the status quo. A theatre critic implored me to ‘memorise all those lines’. He had forgotten that I already knew those lines as the writer of that text. I realised that Lady Anandi further blurred the boundary between a ‘reading’ and a ‘performance’. Can one really claim that reading is not a performative act? Convention dictates the artifice of remembering lines over using them as a device to make the process apparent. This choice of holding the pages of the text was vital to underlining the fact that fiction was filling in the gaps of history, that imagination was replacing memory.

While the performance was designed as a solo, the LCD projector played an integral character in it. I used it to project images on the screen and on my body. When there were no images, I performed in front of the haunting white light of the projector, casting a sharp and constant shadow on the screen, or curtain, or cyclorama behind me. I continually intersected the projector light. This was first a simple device to avoid using theatre lights, but, as the show developed, the stark white light, softened to a yellow one, with the texture of faded pages of history. Each research section was accompanied by an archival photo. And each fictional scene was played out in the yellow projector light – historical research needed photographic evidence but fiction only needed some light and shadow.

Archival photographs formed the core of my performance. In the absence of written documents the images were evidence, of a past of which I had no recollection since I was then unborn. The non-linear narrative of Lady Anandi unfolds through these images. Instead of merely re-enacting these photos, I tried to enter them, projecting them onto my body. It was designed in such a way that ‘the performance was not meant to imitate aspects of the photos, but rather to act as the embodied condensations of complex social attitudes. This form of gesture distils social structures and power relations in a simple pose or condensed scene rather than in a naturalistic imitation of a past occurrence or the impression of history coming alive before-your-very-eyes. With a few stark gestures and movements, I hoped to invoke something of the personal and political complexities bound up in the photographs.’4

It was used to draw the audience’s attention to my living body, which was in front of them in the present moment, and to develop a relationship of this present body with my great-grandfather’s, which was frozen in time. It was also intended to juxtapose an archival image, with all its beauty and historicity, with my body which held its own narratives and was an archive of those experiences and struggles. The audience was presented with the photographic memory of a performance in 1909, and the memory of the current performance was also in the mind of the audience. How would they remember Lady Anandi after watching my reenactment? Where does my body end and the photograph begin? Could my body unravel mysteries of my ancestors if you cut deep into my skin? To quote Eisner again, ‘First: that memory may embed itself within bodies like pieces of glass pressed into the palms and hearts of the tellers and listeners, and secondly then: that these lovingly painful ‘cuts’ are both wounding and life-giving.’5

Another critical, life-giving element in Lady Anandi was its audience. I began presenting Lady Anandi as a work-in-progress, exposing its jagged edges and rawness. In the past, through the theatre-making process I had felt that a performance could be rehearsed several times, but it was only with an audience that its impact became obvious. Otherwise it was like going scuba-diving in a swimming pool – the ocean was missing. In the absence of a director, my audience became the outside eye. There was an in-depth discussion at the end of each show. They questioned every choice, reiterated some decisions, but were overwhelmingly supportive on the whole. One audience member responded saying, ‘I loved that the play was showcased as a work in progress, and was thus fragmented enough to allow the audience to somehow fill those spaces themselves.’6 It was the openness of the audience that allowed such an audacious experiment to be carried forward, to 30 shows across India till date. Another reason for the audience’s response was that it wasn’t just a transaction between the viewer and the performer. The first few shows were non-ticketed but the engagement was intense. It reiterated a belief I have held dear. As performers, if we make our vulnerabilities transparent the audience will accept you, even lift you up, like a buoyant wave in the ocean.

What is a performer without her audience? The writer without her reader? The singer without her listener? As Roland Barthes says, ‘The reader is a man without history, without biography, without psychology; he is only that someone who holds gathered into a single field all the paths of which the text is constituted.’7 This man or woman ‘without history’ as it were, held the key to making new histories, constituting fresh narratives, filling absent spaces with stories, people, images. It was through and in dialogue with that reader, viewer, listener, that a personal story, even a history, could come alive.