John Berger’s writing speaks to me in Punjabi – my mother tongue. I receive it in the way I receive and appreciate music; any music.

I met John for the first time on the 15th of September in 1995. He was at the Institute of Contemporary Arts (ICA) in London to talk about his novel To the Wedding.

I introduced myself: ‘I am the one who wrote the poem ਲਸਣ (Lasan/ Garlic).’ We had not met but he had read it for a film on his life.

After that we exchanged several letters and met many times. I last saw him at his home in Paris, in April last year.

I wrote this poem in Punjabi after our first meeting. Here is an English translation:

JOHN BERGER GIVES A TALK AT THE ICA ON 15.09.95

i hear your voice

not the words you utter

i hear as one touches a fruit

without the need to know what’s inside

as man touches his own kind

as light touches its own colours

your voice –

an echo beyond language

i hear you

as one hears for the first time

i think it’s my voice

just now i touched it with my finger tips

did you hear?

Read the Punjabi original here.

John Berger in Paris, April 2016 / Amarjit Chandan

John Berger in Paris, April 2016 / Amarjit Chandan

A sentence in one of John’s essays ‘whispering to the faded ink of father’s writing’ inspired the next. I sent it to him. He wrote back: ‘I find your poem so beautiful – like an avenue in a city I was wanting to reach. Thank you for it. And tell your father I thank him.’

TO FATHER

As you taught me to write the first letter

Of Gurmukhi – the Punjabi script

holding my nervous hand in yours

You taught me to hold the camera

to focus on faces in the pupil of the eye

and to press the button holding my breath

As if it were a gun

loaded with bullets of life.

Where are you now father?

Can you take some time off from death?

I’d like to take my self-portrait sitting next to you

with a glint in my eyes.

Remember that photograph you took with the self-timer

of us together many years ago

You holding me cheek to cheek?

The photograph doesn’t show the lump in your throat.

We’ll exchange pictures I have taken

of faces you haven’t seen

and of places you never visited

and you can show me yours taken in the valley of the dead.

I had read in one of John’s essays that there is only the present. I sent the following poem to him. He wrote back: ‘Your poem is wonderful, and like a range of mountains takes us very far, to where the little remark of mine was pointing.’

The poem starts with an Arabic word, ‘kun’. It means the act of manifesting, existing or being. In the Qur’an, Allah commands the universe to be – ‘kun!’ and it becomes, fayakūn.

GRAMMAR OF BEING

God uttered a word: Kun Be – and it was.

Be is the seed of all verbs.

So many verbs make a noun.

The noun is the fruit

the seed ripened waiting to be sown again.

It’s the end of the continuous verb

happening in the present perfect

all the time.

The noun is the ultimate verb

of conception of bearing that reaches its end

of no end.

The pyramid rests on the triangled tense.

The noun is the point on the pyramid top

where the journey starts towards the timeless

in the present.

(From left) Sunaina Singh, Amarjit Chandan, John Berger and Gurvinder Singh, Paris, April 2016 / Nella Bielsky

(From left) Sunaina Singh, Amarjit Chandan, John Berger and Gurvinder Singh, Paris, April 2016 / Nella Bielsky

The next poem, ‘Mapping Memories’, has John’s masterstroke.

He changed the line ‘here ends your return journey’ to ‘here ends your returning’. I had sent the poem to him mainly because it deals with his famous concept of ‘the myth of return’ from A Seventh Man. Since then, it has been used in sociology. In the book he says:

The final return is mythic. It gives meaning to what might otherwise be meaningless. It is larger than life. It is the stuff of longing and prayers. But it is also mythic in the sense that, as imagined, it never happens. There is no final return.

But in the poem it happens. I said to him: ‘Here in poetry the myth is broken, John!’ He laughed. Then he read it on camera, saying: ‘I love its cartographic precision and its deep truth.’

MAPPING MEMORIES

Imagine it is a paper.

Look at it.

It is a portrait of the earth.

See where the needle of your magnetic heart stops.

That’s it. That’s the place you always missed.

Put a dot.

Touch it with your fingertip. Softly.

It throbs.

Then put another, and then another till a line is formed –

The umbilical cord reconnecting.

The spot is the cartograph of your memories.

It is the wound healed.

A dot shines on the page

at the zero degree of all directions.

Here ends your returning.

You are home.

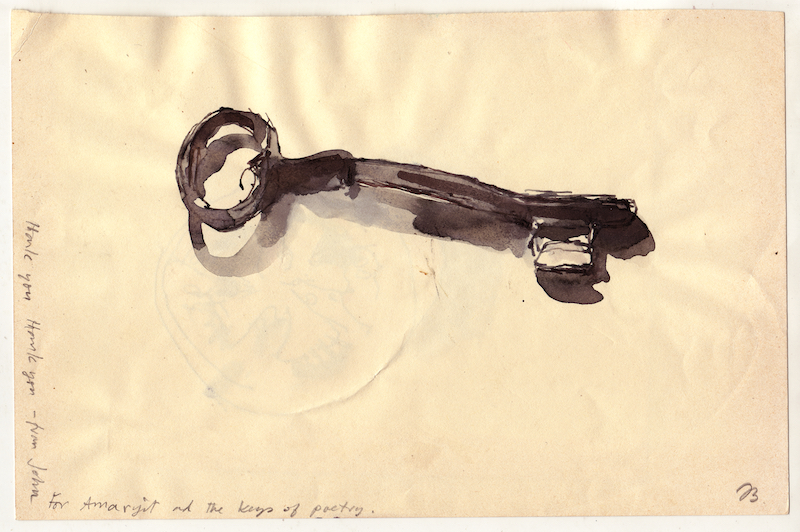

John Berger, ‘The Key of Poetry’, 2012 / Courtesy Amarjit Chandan

John Berger, ‘The Key of Poetry’, 2012 / Courtesy Amarjit Chandan