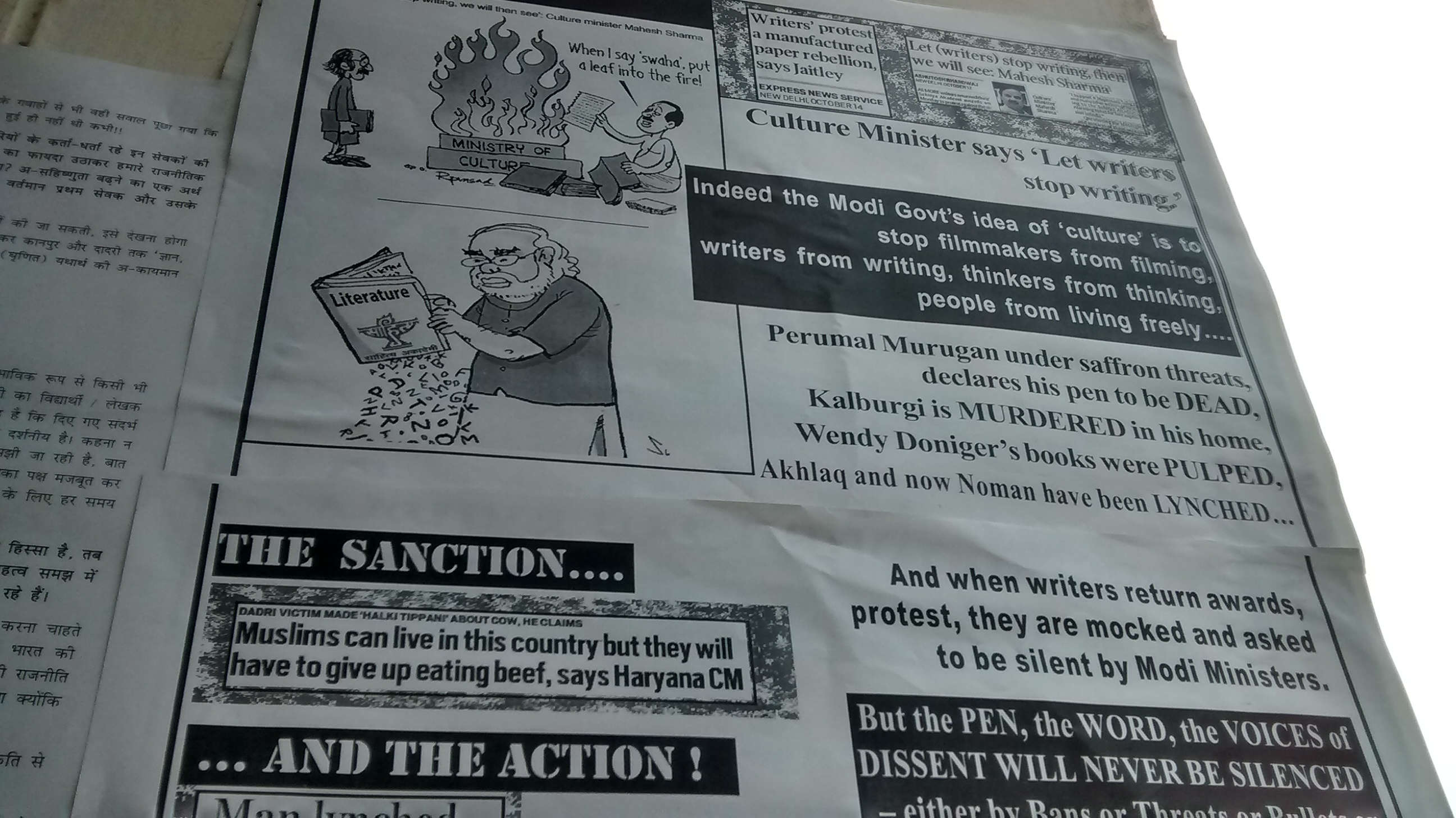

The spate of protests by Indian writers in 2015 — against the murder of dissenting writers and thinkers, and the suppression of freedom of expression — once again proved that our land is not yet barren. The writers were “squeezed like olives”, to recall Joyce’s metaphor, so that they could yield their best. What the writers said, some when resigning from posts in the Sahitya Akademi, some when returning their awards, others in letters and essays, began a chain of protest. Sociologists, artists, filmmakers, academics, scientists — a range of public intellectuals — spoke up in large numbers across the country.

They said many things, but this is a tiny sample:

“We cannot remain voiceless.”

“To writers like me, this is an issue of our basic freedom to live, think and write. Annihilation should never be allowed to replace argument, the very essence of democracy.”

“Your moment of reckoning has come… I do this [return my Akademi award] as an expression of my solidarity with several eminent writers who have recently returned their awards to highlight their concern and anxiety over the shrinking space for free expression and growing intolerance towards difference of opinion…”

“The Prime Minister remains silent about this reign of terror. We must assume he dare not alienate evil-doers who support his ideology.”

“There is a growing fear and lack of freedom under the present government.”

“These incidents are an attempt to destroy the diversity of this country and it signals the entry of fascism into India.”

“We clearly see a threat to our democracy, secularism and freedom. There have been attempts to curb free speech earlier also, but such trends have become more pronounced under the present government.”

“We are perturbed by the attempts at disrupting the social fabric of the country, targeting particularly the area of literature and culture, under an orchestrated plan of action…”

“We are pained by the attacks on progressive writers, leaders of the rational movement and the forcible saffronisation of education and culture… and the communal atmosphere being created in the country… The central government is not performing its duty as the representative of a secular and democratic country.”

“In this land of Gautama Buddha and Guru Nanak Dev, the atrocities committed on the Sikhs in 1984 and on the Muslims recurrently, because of communalism, are an utter disgrace to our state and society. And to kill those who stand for truth and justice puts us to shame in the eyes of the world and God.”

“I don’t think there has been a time when three rationalists have been murdered, and the way in which they were, suggests a resemblance in the crimes. If writers and dissenters don’t protest, who will?”

“What the regime seems to want is a kind of legislated history, a manufactured image of the past, glorifying certain aspects of it and denigrating others, without any regard for chronology, sources or methods of enquiry that are the building blocks of the edifice of history.”

“The writers have shown the way with their protests. We scientists now join our voices to theirs, to assert that the Indian people will not accept such attacks on reason, science, and our plural culture. We reject the destructive narrow view of India that seeks to dictate what people will wear, think, eat and who they will love.”

“Silence is an abetment.”

“The scale of social violence and fatal assaults on ordinary citizens (as in Dadri; Uttar Pradesh; Udhampur, Jammu and Kashmir; Faridabad, Haryana) is escalating… while the actual affiliations of the protesting writers and artists, scholars and journalists may be many and varied, their individual and collective voices are gaining cumulative strength.”

Writers, artists, filmmakers, scientists, historians and other academics and scholars — together, their voices told us about a variety of “official” and “unofficial” efforts to silence dissent and erode constitutional rights. But they also told us that the core of our democracy is still intact.

In his timeless poem “On Wishes”, Palestinian poet Mahmoud Darwish spoke for India in the twenty-first century:

My friend, our land is not barren,

Each land has its time for being born,

Each dawn, a date with a rebel.

The cultural fraternity speaks in two places and in two different ways: in public space, to and along with their fellow citizens; and through their critique of our society, a critique embedded in the nuances, layers and texture of their work. With this issue of Guftugu, we are proud to present ample evidence of this.

K. Satchidanandan

Mala Dayal

Githa Hariharan

January, 2016

Photo by Githa Hariharan

Photo by Githa Hariharan