If any of you die

and leave widows behind;

they shall wait

four months and ten days.

When they have fulfilled their term,

there is no blame

on you if they dispose

of themselves in a just

and reasonable manner.

And Allah is well acquainted

with what ye do.

Quran Al Baqarah 234

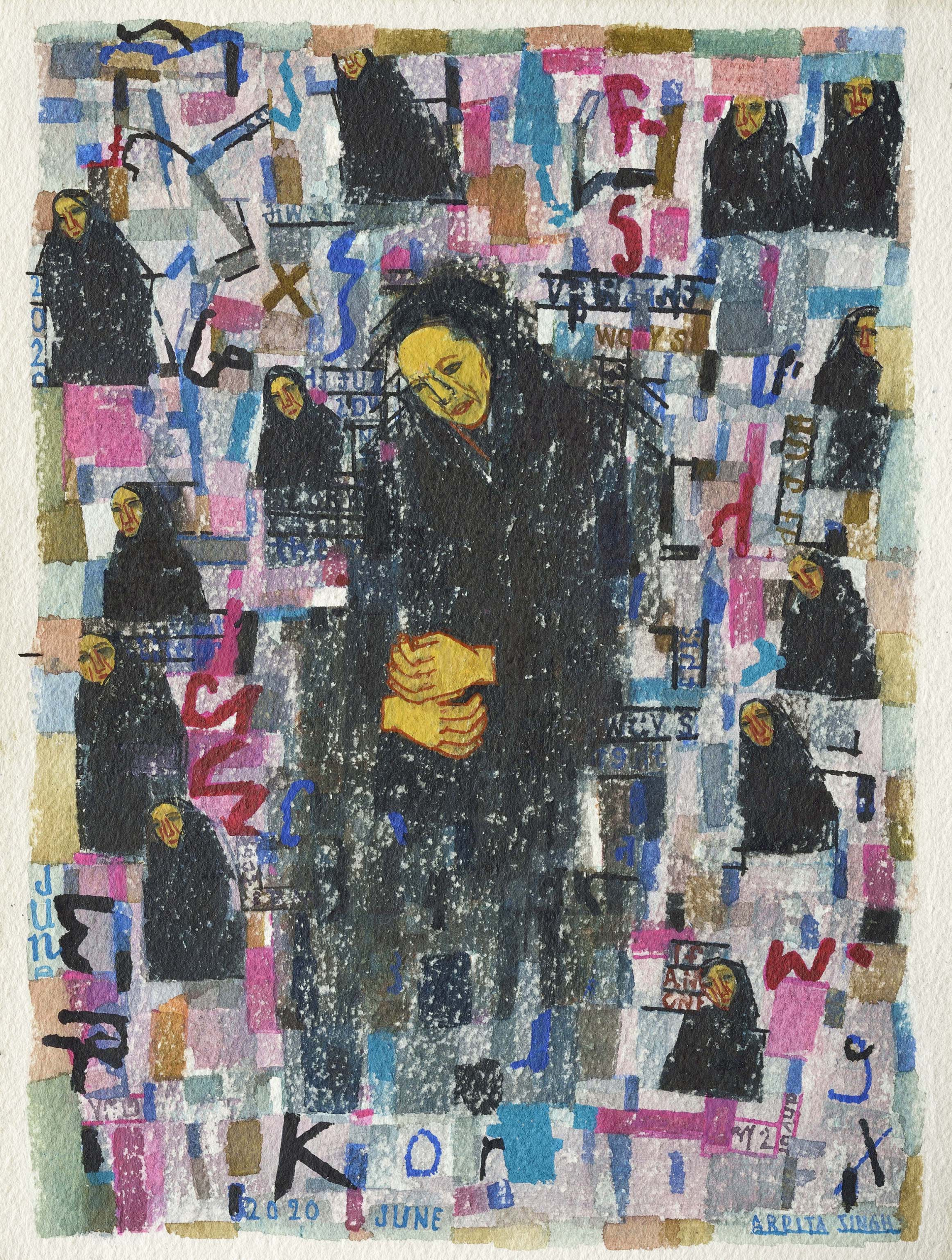

Mehrunissa’s calculation was right. When this night passes into day, Iddath, the period of mourning, will come to an end.

Abbah! It’s gone so quickly. Seems like it happened yesterday. How do I look now?

“You must not look into the mirror during Iddath,” Chikkamma, her stepmother, had said. But the other day, Mehrunissa had caught her reflection in the copper water-pot while bathing. She was startled. Ears bare without the alikhat, all other jewellery locked away in a trunk. No one had seen her take that peep, but the All-knowing, All-seeing Allah had. He holds all the strings. He rewards those who live by the rules.

He would have heard my “Tauba” when I looked at myself. He will definitely forgive me.

You alone can pardon my sins, Allah!

Show me mercy.

For reading the Holy Quran every day for these past weeks,

show mercy on me.

Allah, grant that by reading the Quran

I will remember what I have forgotten.

Lord of the Universe, grant that this Book

will be my life’s anchor. Ameen.

Mehrunissa finished her prayer, raised the Book to her lips, wrapped it in the green cloth, and put it on the table. Then she pressed her hands to her eyes.

Just one more night. Tomorrow she would be free to warm herself on the washing stone near the well. She could sit on the armchair in the veranda and listen to songs on the radio. It would not be a sin. She could comb her hair before the mirrored cupboard in Samad’s room, and Kaijamma would not scold her.

Samad. What was he like now? It seemed like years since she had seen him. But his banter, when he talked to Kaijamma, had forced its way into her room despite her resistance. They would laugh at him, but he still said, “Don’t worry, let all that be, I am here, aren’t I?” So much had happened in those two years! Like a dream, all of it. Anything is possible if Allah desires it. He is the great magician.

Mehrunissa had never imagined that she would be the mistress of such a large house. In her impoverished dreams, even a palace would have a thatched roof.

When Mehrunissa was about fifteen, two monsoons before her wedding, her father was admitted to the government hospital. A week later, he came home on a bier. Mehrunissa’s tears could have drowned the village that day. She rushed into the courtyard where her father’s body was being washed, and rolled on the ground, wailing. Someone picked her up as if she was a bird, and took her indoors.

Why did I weep so much? Because my father was dead? Or because I was afraid of my own fate? Would I have grieved like that if my mother had been alive?

Was Chikkamma, her stepmother, the reason? And yet this same Chikkamma had made her the mistress of this mansion. Who would not have given a daughter to such a wealthy merchant!

On the first night, Puttaba Sahukar had sat his bride on the bed and explained, “You are the mistress of this household. You will not want for anything. Allah has given me enough. You will never have to hold out your hand to anyone for anything.”

Even if she did, who was there to see her? That was not true. There were two others who cared about her.

Thirty years ago, Puttaba had walked the streets of Muthupady with a basket of dried fish on his head. Soon he was riding a bicycle selling fresh fish. In no time at all, he gave up the fish trade and opened a provision shop near the Panchayat office and, before long, built this large house. Behind the transformation of Puttaba the fish seller to Puttaba Sahukar was the story of years of hard work.

Puttaba Sahukar, who had passed away four months and ten days ago, was not old enough to die. Only forty or forty-five. He was not afflicted by any fatal illness. Is it possible to explain what or why things happen in Allah’s game?

Puttaba had an imposing personality. When customers saw him seated behind the counter with a turban on his head, they instinctively called him “sahukar”. If he raised his voice, he could be heard a hundred yards away. A few streaks of grey had appeared in his hair, but his bushy eyebrows were still coal-black. Six months before his wedding, he had six false teeth fixed, but no one could tell. Though his belly had gone out of control, he was stronger than most men younger than him.

This man, who stood out in a crowd, had married Sakina before a hundred witnesses. Barely three months later, Sakina had run out into the courtyard in the middle of the night and thrown herself into the well despite Puttaba’s entreaties. For four days, Puttaba ran a high fever. He clung to young Samad, the boy he had hired to help in the shop, and sobbed inconsolably. People felt sorry for him. Samad, barely fifteen, was frightened by his behaviour.

Vowing never to bring another woman into the house, Puttaba Sahukar sent for Kaijamma, a distant cousin, to manage his household. Suddenly, after twelve years, a month before the monsoon season last year, he decided to remarry, and brought Mehrunissa, twenty-five years younger than him, into the house. Samad smiled to himself under his newly sprouted moustache.

“You don’t have to be veiled before him. Samad has been with me for many years. He is an orphan. There is no difference between him and me in this house,” said Puttaba Sahukar as he introduced the young and virile Samad to her. Samad offered Mehrunissa a bouquet of flowers with affection mixed with respect. The nubile eighteen-year-old girl was seeing such a bright face for the first time. She broke out in a sweat.

Puttaba Sahukar did not come home for lunch. Samad would arrive just as the afternoon call to prayer began, to pick up Sahukar’s lunch box. Waiting by the window, her face pressed to the bars, the tinkle of Samad’s cycle bell gave Mehrunissa much pleasure.

Everything her husband had told her that first night was true. She lacked for nothing. Who but a princess could eat chicken curry twice a week? She only had to mention it, and a juicy chicken leg would appear by her side as she sat twiddling the knobs of the radio. Even her mother could not have given her so much love.

Mehrunissa had no memory of her mother. She had died when Mehrunissa was only a year old. That the woman in the house was not her mother, Mehrunissa had realised very early. Her three stepsisters were born in quick succession, and when a son’s cries filled the house, the responsibility for the girls fell on Mehrunissa’s young shoulders.

Twelve-year-old Mehrunissa’s record of rolling a thousand bidis in a day is still unbroken in the Muthupady bidi factory. Besides working in the bidi factory, Mehrunissa had to bathe, dress, and feed her younger sisters. Her day began before sunrise, when she filled the clay pot to heat water for a bath. Chikkamma suffered from severe back pain and a steaming hot bath provided some relief. Mehrunissa would do the cooking in between the other chores. After lunch, Chikkamma would sleep till four, wake up, nag Mehrunissa, and then go off to the neighbour’s to gossip. She would come home only when dusk had fallen. Mehrunissa’s father, a coolie in Kini’s godown near the bus stand, would leave in the morning and return only at night. It wasn’t as if he was unaware of the badar yuddha going on at home. But every time he spoke a sharp word about it to his wife, her back pain would flare up, and Mehrunissa would have to sit up all night, massaging Chikkamma. Mehrunissa’s father could do nothing to prevent Chikkamma from ill-treating her. The day before he went into the hospital he told his wife, “Don’t be unkind to Mehrunissa. Allah won’t like it.”

Chikkamma had heeded her husband’s last words. Within two years of being widowed, she arranged a nikah between Mehrunissa and Puttaba Sahukar the provision merchant – something she was sure Allah would approve of. Mehrunissa may have been radiant with the glow of youth, but would getting her married be easy? Where would the ten gold sovereigns and three thousand rupees in cash come from? Allah didn’t shower gold and cash from the sky, did he?

Puttaba Sahukar had gold. He had wealth. What he did not have, Mehrunissa had in plenty. As soon as he saw her, he agreed to the match, and thanked Allah for creating this lovely girl just for him.

But when Sahukar extended his hands during the nikah ceremony, his hands shook. Samad noticed this. He would often joke about it later, saying: “Your women are like your fields. Treat them as you wish.”

When the bride was about to leave for Puttaba Sahukar’s house, Chikkamma embraced her, weeping. Mehrunissa was taken aback. Even when they were lifting her father’s body, Chikkamma had not sobbed like this. “You are going into a big house, Unissa… don’t forget your Chikkamma’s children once you are there,” she cried.

Even if Mehrunissa wanted to, Chikkamma would not let her forget. She turned up every other week to ask after Mehrunissa. She brought an empty sack with her and Kaijamma would fill it with rice and coconuts before she left. For whom was her brother accumulating wealth anyway? And Chikkamma’s children were not such distant relatives.

Mehrunissa could not understand Kaijamma. She had never had a confrontation with Mehrunissa. Mehrunissa had sometimes spoken rudely to her. Kaijamma had laughed it off. “You don’t know anything, you silly girl. You have not bathed in as much water as I have drunk in my lifetime.”

Mehrunissa got out of bed, crossed the kitchen and opened the back door leading to the bathing room. A pile of dry wood lay in a corner, waiting to be put under the boiler outside so the smoke wouldn’t come into the house. Whenever Mehrunissa felt dejected, she would lock herself in this room and weep her heart out. If crying could give her relief, she would have bawled so loudly that the paddy mudis stacked in the attic would tumble down. Her pain might have reduced if she could have shared it with someone. But how could she tell anyone that her saintly husband, much older than her father, had fallen at her feet that night and wept like a woman? What use would that have been?

“Tauba tauba!” How could I even think such wicked thoughts!

She poured lotas of water on herself, trying to erase the image dancing before her eyes – Samad, bathing by the well, emptying the large copper pot over himself in one gush, his strong male body shivering a little because of the cold water. Every time she watched him through the crack in the kitchen window she would whisper “Tauba!” and pray that she would be spared punishment by lashing.

Not much longer now. The clock in the veranda had struck twelve a long time ago. Even when Sahukar was alive it had been Samad’s job to wind up the clock once a week. He must be fast asleep now, spread-eagled like a frog.

Soon the chickens in the backyard would begin to cluck. There were many more chickens in the coop then. The twice-a-week meal of chicken saar and akki roti meant that Samad would grab two chickens from the coop, and take them to the nearby mosque to be slaughtered according to the rules. He would buy two more chickens and bring them home, the chickens dangling upside down from the cycle’s handlebar. To this day Mehrunissa had not seen a single chicken escape Samad’s grasp.

Everything Samad did was perfect. He was always enthusiastic, never indifferent. Ask for anything and he’d say, “Leave it to me. I’m here, aren’t I?” Hair pins, tins of kajal, perfumed oil: all delivered the same evening. Puttaba Sahukar was too embarrassed to go looking for plastic bangles or hair clips! Samad had as much authority in the house as Puttaba, and had free access to the cash box in the shop as well as the pickle jars in the kitchen.

But the keys to the shop were always on Puttaba Sahukar’s waist. The key bunch hung from a specially made thick leather belt, and Puttaba insisted on opening the shop every morning and shutting it at night. It was a strange obsession. Samad had never touched the bunch of keys. Nor had he wanted to. His mischievous smile did not need doors or keys to enter any room.

The only time Samad’s broad face looked serious and anxious, it was for exactly eight days. During that time, the big brass lock remained untouched on the wooden door of Puttaba Sahukar’s provision shop.

One evening, barely a month after Ramazan, Puttaba Sahukar came home earlier than usual, refused his dinner and lay down, complaining of mild chest pain.

Mehrunissa immediately thought of her father. While she sat by her husband’s side, massaging his chest, she could hear Samad talking to Kaijamma in the room with the mirrored cupboard. He came to the bedroom door a couple of times and asked, “Shall I get the doctor?” Puttaba waved him away.

The next morning, when Puttaba Sahukar showed no signs of getting up, Samad looked grim – something that Mehrunissa had not expected – and said, “Whoever can decide whether to call the doctor or not does not lie in bed like this. Leave it to me. I am here, aren’t I?” He left like a gust of wind. Mehrunissa couldn’t believe it.

The worried look did not sit well on the face that broke so readily into a mischievous smile.

Puttaba had a heart like wax. It melted at the mention of sorrow or pain. But he wasn’t so stupid that he didn’t notice the admiring glances Mehrunissa threw at Samad.

Using poor light as an excuse, Puttaba moved his bed to the room with the mirrored cupboard. He did not want the doctor and Samad barging into his bedroom ten times a day. Mehrunissa never stepped into the room when Samad was in the house.

Puttaba and Samad left the house together after the morning tea and returned only in the evening. Mehrunissa had the house to herself. She would stand in front of the full length mirror all day, stroking her golden, smooth-as-silk stomach, sighing.

Puttaba suffered for only four days. On Thursday night he seemed slightly better, but on Friday morning he did not open his eyes.

Puttaba saw Mehrunissa’s long dark serpent-like hair reflected in the mirror and said sadly, “I have done you great injustice. Who will be there for you now?”

“Don’t worry. I am here, aren’t I?” said Samad. “I am not one to give up so easily. The doctor refused to come at night. But I grabbed his bag and ran.” He paused then turned to Mehrunissa. “Please go inside,” he said to her, and he summoned the doctor. Her husband’s last words faded away even before they were uttered.

Samad had remained awake all night but had dozed early in the morning. When he woke up, the crows were circling above the courtyard.

Oh peaceful soul, return to your God.

You will be happy there,

He too will be satisfied with you.

Join those in my service

and enter my heaven.

From the courtyard came sounds of voices, footsteps, wailing, consoling. In the bedroom, Mehrunissa sat alone, her face on her knees. “Don’t talk to her. Let her cry herself out till she is dry,” she heard Kaijamma tell someone. Boobamma, her daughter Saramma, and Radhakka were all there. How had the news spread so fast? Chikkamma had dragged her two youngest ones along with her and was demanding to be the chief mourner. Even Kaijamma found Chikkamma’s wailing, “What will become of you now, Unnissa?” intolerable.

When Mehrunissa had thrown herself on her husband’s cold body, Kaijamma held her and took her to her room. “Stay here, child. There is no use grieving. You have to face what has happened. Besides, what has happened? One person less to talk to, that’s all, isn’t it?”

Hmmm. How does Kaijamma know everything? Within four months of becoming mistress of the house, Mehrunissa had discovered that nothing could be hidden from the old woman.

One day, just after Samad had left with Puttaba’s lunch box, Kaijamma held Mehrunissa’s arm and said, “My child, even I was young once. Puttaba is very tender-hearted. He will not harm even an ant. You know that. Whether you immerse him in water or milk is up to you.” Mehrunissa fell at Kaijamma’s feet and sobbed bitterly. Kaijamma’s eyes also filled up. Kaijamma never had to speak to her like that again. Mehrunissa’s behaviour did not warrant it.

Samad knew hundreds of stories. Some he had heard, some he had made up. When Mehrunissa and Kaijamma sat by the well plucking a chicken, Samad would join them and tell them stories about brave princes and beautiful princesses. The prince would enter the seven-walled fort in the garb of a guard. The soldiers would try to capture him. He would mount his white Arab steed and fly off into the sky. Or, if the prince set off to fetch the pearl necklace the princess wanted, he would climb his magic horse and cross the seven seas and reach the fierce demon’s cave. When the demon took the form of a pig, the prince would turn tail and run away. Samad’s stories had humour too. The women would forget the chicken and lose themselves in the adventure. When the story ended, Samad would clap his hands and laugh aloud, bringing them back to reality. An embarrassed Kaijamma would scold him, “Now will you get out of here or shall I tell Puttaba to stitch up your tongue?”

Even after Samad had gone back to the shop, Mehrunissa would wander around the seven-walled fort with the prince till Kaijamma brought Mehrunissa out of her reverie. And each time this happened, Mehrunissa would bite her lip and admit her guilt. But the day her husband died, the prince who pushed his way into the seven-walled fort and went straight for the throne, startled Mehrunissa.

After the ritual bathing of the body, prayers were recited in the courtyard. Soon they would carry his body away. Then there would be no man in the house. Mehrunissa trembled with fear. Just then she heard footsteps. She looked up. Samad was leaning against the door. She stood up cowering against the wall, her heart thudding. Samad must have heard it.

“Want the keys to the shop.”

Mehrunissa’s blood ran cold. Her lips trembled, her mouth went dry.

“Need to buy agarbattis. Also require some cash.”

Her legs wobbled. She felt faint, but she steadied herself and sat down on the bed. Her right hand reached for the bunch of keys under the pillow.

Puttaba Sahukar always kept his beloved keys under his pillow. He had told Mehrunissa, “You see these keys? They are mine. Only I have the right to them. My elders left me nothing. I have worked hard and earned all this. Not by breaking anyone’s head. You must keep these keys safely.”

Mehrunissa had fulfilled her duty diligently. When Puttaba returned from the shop, he would unhook the bunch of keys from his belt and hand it to Mehrunissa. She would tuck it under his pillow every night, and hand it over to him before he left for the shop the next morning. This had been the practice for the last two years. Even Kaijamma had never touched the keys. But the day Puttaba was moved to the outer room, the bunch of keys had remained under his pillow in the bedroom.

“It’s getting late. Where are the keys?” This time it was not a request. It was a demand.

Lord of the universe, Allah,

if You wish it, You grant authority.

If You so wish, You snatch it away.

You reward those who You please,

You are capable of executing all things.

If my thoughts are wrong, forgive me.

Biting her lip, Mehrunissa stood up, reached for the keys and held them out to Samad.

As a child, Mehrunissa had learnt that crows begin to caw before the sun rises. Daylight would nudge its way into the room in another hour. Mehrunissa had got used to waking up for the morning namaz because of Chikkamma. No one would question her if she woke up at ten o’clock in Puttaba’s house. Kaijamma could manage all the work, but after Mehrunissa said her morning prayers, she would begin work in the kitchen before Kaijamma could protest.

But when Mehrunissa sat for Iddath, Kaijamma had to do everything. Mehrunissa was not supposed to step out of the room, except to go to the bathroom. No male eye was to fall on her. If there were children, it was different.

Surprisingly, she had no trouble adjusting to the new routine. It was not very different from her life with Chikkamma. Except visiting the government hospital when ill, or the annual fair, the Muthupady Urus, she had not stepped out of the house anyway.

What with looking after her sisters and rolling bidis, she had no desire to meet strange men. But when she heard Chikkamma making plans for her marriage, she must have had some vague dreams. But she had no clear idea about the man she would marry. So she was quite happy to be Puttaba Sahukar’s wife. Who would not want three good meals a day without having to roll bidis?

The main change in her routine after Iddath was not going into the room with the mirrored cupboard and the veranda. She used to visit Maimoona sometimes to play with her child. But she did not miss those visits. They brought more humiliation than happiness.

Thirteen days after Puttaba Sahukar’s death the fatiha took place. The next day Kaijamma said hesitantly, “The shop has been closed for so long. The provisions in the house won’t last forever. What should we do?” Kaijamma left the decision entirely to Mehrunissa.

It was not difficult for Mehrunissa to answer her question. Puttaba used to tell her about the business – how much profit he had made, what they would do if the price of coconuts suddenly fell. “Make coconut chutney and plaster it on our heads, what else can we do?” he would say then doze. Mehrunissa would lie there, staring at the ceiling, coaxing sleep to come to her.

Kaijamma waited for Mehrunissa’s answer.

“I’ve told Samad I will speak to him in the evening. There is nothing wrong if he asks what is to be done. He is a man. He must know what he has here. We can tell him to leave. But who else do we have? Think over it till the evening,”Kaijamma said and walked away.

The key bunch still lay under the pillow. Samad had taken it the day her husband died, and returned it through Kaijamma the same evening.

Mehrunissa tried to read the Quran but a hundred thoughts ran through her mind. Which other man can take charge of the house? Had Kaijamma been suggesting something this morning? Would he walk away if they told him to go?

He may not be a blood relation, but he came to this house before I did. He too has a share in the property. He is a man, what if he tells Kaijamma and me to get out and becomes the owner of the house? Mehrunissa shuddered.

Will Samad send me away? Chhey! He is not like that. I will remain the mistress here.

So what did Kaijamma have in mind? Tauba, tauba! Mehrunissa rubbed her eyes then focused them on the lines of the Quran.

During the period of Iddath,

discussing remarriage with the widows or considering it

is not wrong. Allah knows everything.

However, until the period of mourning is over,

do not take a decision about marriage.

Allah will be aware of it.

Be fearful of Him.

He is compassionate and merciful.

When Kaijamma brought Mehrunissa’s lunch into the room that afternoon, Mehrunissa held out the keys to her. Kaijamma took them without a word. She did not like chatting with anyone in Iddath. She was now saddled with another job – taking the keys every morning and bringing them back at night. She did not refer to the shop, nor did she mention Samad. Mehrunissa did not ask. Reading the Quran all day and spending the night in restless sleep – that’s how four months and ten days had gone by. But when Kaijamma came for the keys or when she returned them, Mehrunissa’s thoughts galloped out of control.

Samad did not come home for lunch. Kaijamma had casually mentioned that he had employed a small boy to take his food to the shop. Mehrunissa did not react.

Allah, who controls the movements of the Sun and the Moon,

save me from the torment of hell.

Keep the doors of heaven open for me.

For those who have feared Allah, there are two heavenly gardens.

Gardens with spreading green trees,

each bearing two kinds of fruit

within reach. Reclining under them,

on silken cushions, honourable women. Not just beautiful,

but chaste, virtuous,

untouched by man or devil.

He who fears the Lord will be bound in matrimony

with a beautiful large-eyed woman.

A shiver went through Mehrunissa as she finished her namaz. The words thrilled her. She prayed that her husband would receive all these pleasures. And she?

Being born a woman is a grave sin. So where’s the question of rewards?

She saw daylight creeping in through the window. In a few minutes, everything would be bright. She heard sounds from the kitchen. Must be Kaijamma. Samad woke up late.

She had often seen his reflection as he lay by the window, legs spread wide, the sunbeams making a halo around him. Was he sprawled like that today? It was four months and ten days since she had seen his face.

Kaijamma called out from the kitchen, “Are you awake, child?”

She asked the same question every day during the Iddath period and Mehrunissa did not bother to reply. But today she felt like answering. It was not a sin to go out now. But go where? To the kitchen? What would Kaijamma say?

Let her come and call me.

Putting away the Quran, touching her eyes with her fingertips, Mehrunissa lay on the bed. She had waited so long, what were a few minutes more?

She heard Samad talking to Kaijamma in the veranda. It was not yet time to go to the shop. She waited eagerly for Kaijamma to come and take the keys. But she didn’t come. The front door opened then closed. Mehrunissa was surprised. Where could Samad have gone?

When Kaijamma came in with her breakfast, Mehrunissa was perplexed. Had she miscalculated? She marked the pages of the Quran every day. Kaijamma had told her yesterday that she did not have to wait much longer.

Why didn’t she call me to the kitchen then?

Swallowing the question rising in her throat, she reached for the plate.

“Puttaba couldn’t stand menthe dosai,” Kaijamma said. “Samad loves them. Asked me to make them yesterday.”

Mehrunissa became suspicious. She peered at Kaijamma’s face but there was no deceit in her eyes.

“Samad is not going to the shop today. He is going to Kasargod,” Kaijamma said casually.

“To Kasargod? Why?”

Picking up the empty plate and glass, Kaijamma said, “He made me swear not to tell you till the Iddath is over. The Kasargod party has been after him. He told them, in my presence, that only when you go approve of the girl can they take things forward. He has gone to inform them that the girl-viewing will be next Thursday or Friday. My time is limited. You must like the girl who will come as your daughter-in-law. Samad has also agreed. If you say yes, he will marry her – even if she is blind or lame. Anyone must have done some good deeds to get a boy like Samad, isn’t it?”

Mehrunissa did not faint. In a daze she prayed,

Oh Allah!

Let fall the red scalded sun on a sinner like me.

Make me tread boiling water,

pour molten copper over me…