Two Kinds of Realist Cinema

A welcome development in the past decade has been the gradual erasure of the distinction between the art film and the popular film – at least in formal terms – with the commercial successes of film-makers like Anuraag Kashyap and small films like The Lunchbox (2013). The difference between the two kinds of cinema – art and popular – arose because they came out of different impetuses. Popular cinema may be regarded as a continuation of the puranic narration and the Indian epics, while art cinema derives from the novel. Where action and characters in the popular film are heroic, those in art cinema have been closer to ordinary life. Art cinema, although it began much earlier (perhaps with the IPTA and K. A. Abbas’ Dharti Ke Lal, 1946) really got going as a movement around 1970 through state intervention and the formulation of a national film policy. Although it had a sizeable public in the 1970s and 1980s, art cinema is now largely dependent on state patronage; where it had once functioned as the liberal conscience, it has become habituated to dealing with issues considered important by the state — like rural indebtedness and communal harmony — without the possibility of subversion.

It is because the art film derives from the novel rather than the oral tradition that it needs a public with education, broadly familiar with the strategies of fiction. One could argue that with the development of new economy businesses after 2000 there has been a gradual movement of educated people (especially those who are Anglophone) into the metropolitan cities, and it is this public which has made realist fiction possible in popular cinema as well — a cinema which tries to tell stories instead of playing a conscious social role, realist cinema as entertainment.

The art film and the popular film are both national although in different ways. Art cinema has tried to direct the destiny of the nation by dealing with the social issues needing to be addressed, while popular cinema has enabled a large public distributed across a heterogeneous cultural space to imagine the nation. Benedict Anderson argued that the novel and the newspaper helped sustain the nation since they facilitated a community of readers to collectively imagine it; in India, where the level of literacy has been small, popular cinema has similarly helped a widely distributed public to collectively imagine the nation and help sustain it after 1947. Needless to add, their dissimilar roles means that the nations the two kinds of cinema posit are also different from one another.

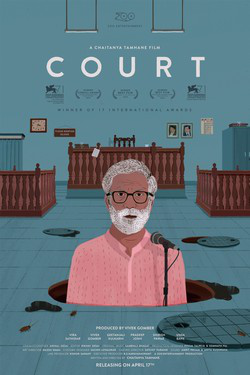

The last year has been a fertile year for realist cinema in as much as it has produced highly acclaimed realist films, both in the art film and the popular film category. Where Indian art cinema has had an unremarkable stretch after 1990 and the commencement of the economically liberalized era, Chaitanya Tamhane’s Marathi film Court, which won the national award for best film, can be justly regarded as a watershed. On the other side, in times when popular cinema has celebrated affluence and ostentation unreservedly, M. Manikandan’s Tamil film Kaaka Muttai has contrived to turn a story about slum children living in poverty into a popular film success. This essay compares the two films, but its purpose is not to judge them, but to understand the nations that the two portray because they are unlike each other.

Chaitanya Tamhane’s Court

Chaitanya Tamhane’s Court begins with an elderly dalit activist and singer Narayan Kamble (Vira Sathidar) being arrested by the police on the charge of abetting suicide. A worker in the municipality, Vasudev Pawar, died while cleaning the sewer, and since he did not use safety equipment his death is considered deliberate and tantamount to suicide. Narayan Kamble gave a performance in the vicinity of Mohan Pawar’s tenement two days before his death advocating (in song) suicide as a preferable alternative for municipal workers, rather than climbing into sewers. Narayan Kamble’s case comes up for hearing and his advocate is a socially conscious young lawyer Vinay Vora (Vivek Gomber), who is unable to get bail for Kamble.

Much of Court takes the shape of court hearings and the film is filmed so authentically – with no indication of the actors being conscious of the camera – that one might even take it for documentary. Making it highly effective is the courtesy constantly on display: the judge being sympathetic but not granting bail, the police inspector being polite but presenting a phony witness, the prosecutor Nutan (Geetanjali Kulkarni) being human and considerate but often arguing ludicrously — equating the dalit folk-singer with a terrorist and then turning this labelling into a hypothetical one (“just suppose he had been a terrorist”). Narayan Kamble spends months in jail as the hearing gets postponed time and again. The judge has the reputation of being sharp but — as in actual courts — his tolerance of weak logic from the prosecution is astonishing. At the climax of the film Vinay Vora manages to get Pawar’s wife to give evidence and it comes out that Mohan Pawar was never given safety equipment; his only way of telling whether it was safe to go into the sewers was through the presence of cockroaches. If cockroaches came out it meant that the sewer was free of gas. Pawar was always inebriated when he climbed in because that was the only way he could stand the stench. And despite using cockroaches as safety equipment, Pawar had also lost one of his eyes.

As a social document the film should not perhaps be praised for its authenticity and one instance of its inauthenticity rests in Narayan Kamble being completely alone spending months in prison without bail; a dalit activist in a city who addresses a public from platforms is potentially political capital, and one would expect politicians of more than one hue to be willing to assist him because of the constituency he commands. Tamhane is perhaps relying too much on the art film convention of the dalit as politically helpless (as in the cinema of the 1970s and 1980s) which might not be true of an activist with a constituency today. But more important to an appreciation of the film is the sense created of the vast gaps existing even between the marginalised in India and the middle-class activists sympathetic to them, like their advocates. A very powerful scene in the film shows Vinay Vora driving Mohan Pawar’s widow in his car after she has tendered evidence and the woman being completely incommunicable since there is no way that a middle-class activist — regardless of how well-intentioned s/he may be — will be able to understand the true predicaments of those they represent. This is not simply a portrayal of misery but the picture of a nation/society rent by divisions so immense that even to speak of a national community is a travesty. I described art cinema as having been the nation’s liberal conscience but Court suggests that the notion is not pertinent because of the way the nation has excluded most of its subjects from its development. The banality of the courtroom discussions in this film when contrasted with the high drama of Aakrosh (1980) also points to public faith in state-administered justice slipping. These aspects of Court come into especially sharp focus when it is compared with Kaaka Muttai.

Image courtesy https://madaboutmoviez.files.wordpress.com/2015/04/kakka-muttai-movie-poster.jpg

Image courtesy https://madaboutmoviez.files.wordpress.com/2015/04/kakka-muttai-movie-poster.jpg

M. Manikandan’s Kaaka Muttai

Manikandan’s film is set in a slum in Chennai and tells the story of two brothers who help their mother (Iyshwarya Rajesh) keep their home running by picking discarded coal beside railway tracks, and eat crow’s eggs to supplement their modest meals. Their father is in jail for some unknown reason, and the story starts moving when the tree from which they filch crows’ eggs is brought down to clear the space for a pizzeria. A short while later their mother receives a television set as a gift from the government — meant for those ‘below the poverty line’ — and it is on television that the boys see the object which creates the first disturbance. What the boys see on television is an advertisement for pizza. The way the pizza is shown makes them yearn so much for it that they can scarcely rest until they raise the Rs 200 needed to purchase one at the pizzeria. The boys contrive to get more coal than usual through a well-wisher and save up some money. It is not adequate for a pizza but their grandmother makes an imitation pizza — a dosa with toppings — which they pronounce inedible. A middle-class friend offers them pieces of the divine object but the boys want an entire pizza. Eventually, the boys raise the Rs 200 but the watchman shoos them away. This means they have to get new clothes as well, and they get them through a trade arrangement with some middle-class boys. But when they get to the pizzeria in brand new clothes they are still shooed away. To worsen matters, the manager slaps the older brother and knocks him down. But, unknown to them, the entire episode has been caught on a mobile by another slum boy. This mobile now falls into the hands of two idlers from the same slum and the cleverer one manages to get an offer of one lakh from the owner of the pizzeria to keep the footage from reaching the media. A businessman slapping a bonafide client for being poor will not look well. But before the transaction can be concluded, the idler’s companion hands the footage over innocently to a television channel, and it goes viral. The film concludes with the boys being welcomed ceremoniously back into the pizzeria and given pizzas to eat. But the two are disappointed and compare what they taste unfavourably with the dosa made by their grandmother, now unfortunately dead.

It will be evident to the reader from this description that Kaaka Muttai deals with a more cohesive world than the one in Court. The film is presenting a real world in which there is genuine poverty as well as affluence, but there is little sense of there being a group classifiable as the marginalized. In the first place everyone is integrated into the economic mainstream with comparable aspirations, although the choices one makes might be different in the actual products chosen. It can be proposed that there are enormous segments in the informal economy which get by only by subverting legal processes. As an instance, people who subsist on railway coal may need to do more than search patiently for the lumps which have fallen off trains on their own. The sense of everyone being integrated into a single economic mainstream is also furthered by the discourse around the pizzeria. The owner of the establishment can be understood as belonging to an older feudal India in which one chose one’s customers based on their stature. Kaaka Muttai is the product of an economically up to date India and shows the right kind of capitalism at work when the pizzeria’s feudal ways are exposed, and the slum children admitted as legitimate customers, when they can pay for whatever they eat. Passing a judgement on the pizza after it has been eaten is the legitimate right of the consumer and this is also affirmed. The sense of cunning/subterfuge being necessary for the weak to survive — which infused fairy tales and the stories of the Panchatantra — is notably absent and only financially legitimate dealings are allowed. Another motif that needs comment is that of the father in jail, without his incarceration being questioned or explained. The man loves his family and they love him back, but he remains in jail, and the resolution of the film does not include his release. The father being in jail is, therefore, used as a mere detail to illustrate the fates that slum-dwellers tend to suffer. The argument here is that this detail points not only to the criminal ways that the poor are forced into, but also to the even-handedness of the law which punishes, but only to the extent of one’s errors.

Kaaka Muttai is very authentic in pictorial terms but it furthers a mythology that one finds dubious. Its sense of social cohesiveness was not exhibited by Hindi cinema before 1990, in which there was an admission that a life of illegality is often the only way out for the marginalised. A society is cohesive if the state mediates effectively among private citizens, and interests and illegalities happen because of inadequacies in the functioning of the state; those who do not have the benefit of its asymmetric umbrella are among those who seek benefits outside it. The fact that films like Deewar (1975) conclude with the triumph of the law does not neutralise their discourse on the inevitability of illegality in a certain kind of existence. Since one cannot believe that India has become a more cohesive space socially between 1975 and the present day, one is led to see the realism of Kaaka Muttai as an exercise in which cohesion serves an ideological end.

The social cohesiveness implied by Kaaka Muttai, as I have tried to show, is infused with a belief in an inclusive economic mainstream, and this is the mantra of those who hold that the trickle-down benefits of economic activity will eventually include everyone. Popular cinema has come some distance from the post-liberalisation ostentation of Hum Aapke Hai Kaun, but Manikandan’s film may be the first to alter popular film discourse, from the poor as a footnote in the life of the nation, to the more insidious — the poor and the rich are equal cogs in its economic well-being. Kaaka Muttai is a Tamil film and it is perhaps only Tamil Nadu — in which there has been a semblance of lower-class empowerment — where such a view will not strike audiences as patently absurd. One need only imagine the film with the slum boys taken from Mumbai to perceive this.

The feel-good film

Kaaka Muttai is described as a “feel-good” film and it is so in the sharpest sense of the term. A “feel-good” film is not simply a film with a happy ending, but one which offers a reassuring social vision to it’s audiences — though this reassurance could also be metaphysical as in Forrest Gump (1994), where fate intervenes relentlessly to make the mentally disadvantaged protagonist triumph at everything. I have conveyed the gist of Kaaka Muttai through its story, but the film also uses every formal means at its disposal to suggest an ordered society in which everyone takes his or her rightful place. The exchange of glances and smiles is one way in which it achieves this sense of perfect communion. This is entirely different from Court where people scarcely make eye contact — not even the dalit activist and his advocate. To use Bakhtinian terms, Court is “polyphonic” in its conception because it suggests the multiple voices that do not come together, creating a tumult which the liberal nation state is unable to contain. Narratives naturally accommodate a multiplicity of voices simply because people in society live according to different visions of human existence. But these voices are polarised and the multiplicity quelled when there is a single purpose at work in a text — such as nationalism or patriotism — when every voice echoes this single purpose. Where Court is true to the polyphonic character of society, Kaaka Muttai is a fantasy of economic communion; those who are made to “feel good” by it are evidently those who share its totalitarian vision of a nation marching ahead with one goal in mind — an economic one which allows no diversions. This leads us to wonder if all “feel-good” films are not, in some sense, totalitarian.