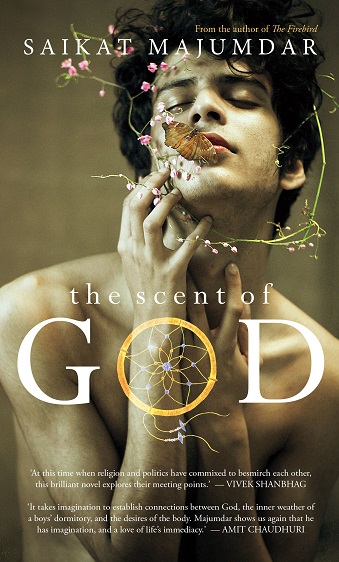

Saikat Majumdar is a novelist and critic. His latest novel The Scent of God, published by Simon & Schuster India, is a story of two teenage boys grappling with their mutual attraction in an elite boarding school run by a Hindu monastic order. Set in the late-twentieth century India, The Scent of God explores same-sex desire in an institution that criminalises that kind of love. Excerpts from the chapter ‘The Lotus Position’ of the novel and a conversation with Kanika Katyal underline the relevance of this work in today’s cultural climate.

Kanika Katyal: How do you see the ongoing misuse of religion and religious places of worship?

Saikat Majumdar: I left the US in 2016, the year of Trump and Brexit. The reality of an angry, poor white population that bared vicious fangs from a sharp sense of disenfranchisement following everything from globalisation to eight years under a black President, still feels warm and real. That reality still smoulders in the West. The Indian story is far more frightening. You might dismiss the Hindutva crusader as a tilak-tattooed, tika-waving deprived plebeian who has nothing but the opium of religion, but the larger structural condition of his existence is made possible by the very enfranchised and empowered middle and upper-middle class Hindu male. I’m sure the equivalent exists in the rich right-wing white male in the US – Trump himself is the example of that – but the primal energy of white nationalism comes from a poorer class in the US, somewhat like the poor Boer in early 20th century South Africa who crafted apartheid and gave it a perverse moral legitimacy.

Which is to make the bizarre admission that I feel a modicum of sympathy for the poor whites in the US, but the smugness and disdain in the urban Hindu middle and upper-middle class really upsets and frightens me. I don’t see the map of an easy exit out of this.

Secularism, I’m afraid, is a poor answer. India will never be a secular country. Religion is too important for the vast majority of people here. But it can be a pluralistic culture, as someone like Akbar had imagined. And honestly, religion is too important to be left to the fundamentalists. Bourgeois intellectuals and thought-leaders have done so, and the only people to take ownership of religion have been right wing ideologues. How can one take religion back? Is it possible to create, or perhaps revive, a Hindu Left? What role may artists and intellectuals take in crafting compelling narratives around religion, a subject that has inspired moving art, performance and stories for hundreds and thousands of years? How can such narratives sing to populations most deeply oppressed by the various incarnations Of Hinduism through history?

From The Scent of God:

Saffron sheathed Kamal Swami like skin. He was a taut bowstring, flashes of energy tossing around the smooth cotton and revealing fair, hairy flesh, patches of sweat that darkened the amber fabric as he breathed faster and faster like a stallion while Anirvan forgot to breathe, staring at muscles that shot out as saffron seawaves. His heart stopped at the glimpse of his fair and lean arm as the Swami rolled up his sleeves on the badminton court. He dreamt of owning such arms one day. These very arms.

He was a saffron soldier with the eyes of a boy, eyes that sparkled with love and mischief but which never failed to hunt down the heap of dirt the students had swept under their beds or the cricket-magazines hidden under geography textbooks. The boys’ rooms were restless, with blobs of shame hidden in odd cracks like the wet towels and the used underwear they forgot to give their mothers on Sunday.

The Swami knew everything.

The boys had marched out of the common room in silence that day. After the TV was killed and they were thrown out of the stadium in Peshawar. The air was thick with war. The firecrackers had gone out in Mosulgaon but anger smoldered at the sudden death of the match.

Kamal Swami stood at the door while the boys walked out quietly, all eighty of them. His fair face looked red and stormy.

‘The two of you wait here,’ he said softly as Anirvan and Kajol stepped out.

They waited. They were anxious but they didn’t want to look at each other.

‘Those boys are a shame,’ Kamal Swami told them after everybody had left. His voice throbbed with passion. ‘Animals, all of them.’

Anirvan and Kajol stood in silence. They looked down, wilted in shame. They didn’t know what to say.

‘You boys stay away from them.’

His voice was kind. Kind but cruel.

‘From now on the two of you will sit at the back of the prayer hall.’ He said softly. ‘I want you to watch if any boy makes trouble. Just tell me if you see anything.’

What was Kajol thinking? Suddenly, the question screamed inside Anirvan’s heart.

‘You will spread out our prayer mats before prayer.’ The Swami said. ‘And put them back after it’s over.’

Every night after the lights were off the Swami sat on the wooden bench outside his room and spoke about life, death, and life beyond life. When the day was over and their duties done, his voice was softer, kinder, and sometimes almost aimless. The boys could not see his face in the dark but his affectionate hands caressed their shoulders and the backs of their necks and slid along their arms in ways they never would in daylight. It was good to sit right next to him but it was not always possible because many boys crowded the bench after lights-off. But his voice melted in the dark and floated everywhere even if you were not lucky enough to sit next to him that night. He said the most beautiful things. Once Rajeev Lochan Sen had popped a tough question about the point of studying history. It was a scrap of a debate that floated in school for days.

‘Is history a dead subject?’ The Swami had laughed. Under the nightly softness, the laughter had a bite, and Anirvan imagined the pointed edges of his crooked teeth glistening in the dark.

‘Go and look at yourself in a mirror,’ he said.

‘Mirror?’ Rajeev repeated, full of wonder.

Kajol had walked into the gathering tentatively. He looked like he had lost his way.

‘Move over,’ Kamal Swami said. ‘Kajol, sit next to Anirvan.’

There was no place next to Anirvan. The slight-framed Kajol came and sat on Anirvan’s lap.

‘Take a hard look at yourself,’ the Swami’s voice softened. ‘What you see in that mirror is history.’

Rajeev was lucky that night. He was seated next to the Lotus.

‘This face, this neck, these shoulders,’ the Swami’s voice trailed in the dark. ‘The messy hair and the frown. The clothes you wear.’

‘You’ll see all of it in the mirror, won’t you?’ the voice floated, suddenly happy and boyish.

‘This is history,’ it said. ‘And you ask whether history is a living being?’

Rajeev was silent. Anirvan wondered if his doubts were gone. But Anirvan didn’t care anymore; he felt lightheaded. Kajol’s childlike frame rested on him, and he could smell soap and talcum powder on his neck.

Anirvan knew why the Lotus was so brilliant at carrom. He could handle his mind like the red striker on the board. Anirvan had tried it too. He thought he could do it. Leave your mind, swim out of it, and watch it wander. The Great Saffron One had said a hundred years ago. Watch it like a fish bobbing in the water, a trivial thing of colour that is no longer part of you. Anirvan could lose his mind in the prayer hall, during the meditation time at the end, at least for a minute, two minutes, two minutes and twenty seconds…

KK: Why makes The Scent of God so relevant in today’s political and cultural climate?

SM: One doesn’t think of political and cultural relevance while trying to create art – at least I don’t. Stories come from a different place, and when they come, they choose you, rather than the other way around. They leave the writer little conscious agency in the naked newborn act of telling. But it’s also true that we share the spirit of the age. After the writing is done and we return to consciousness, we wonder at the ways the strange and private stories we tell are also the stories of our times.

Suddenly the two kinds of stories appear braided far more closely together than we thought. The Scent of God came to me half a dream, half real, a world real but invented, smelling of a universe where I had once lived and whose texture suggested to me moments and experiences that could potentially come to life, though I don’t have real evidence that they did. A story of romantic passion between two teenage boys that take an unlikely turn is strange enough; what is the fate of that romance when it blooms in a monastic boarding school?

A story like this comes to you from a forgotten crevice of light and shadow far back in your life, and just when it’s about see life in print, Article 377, criminalising same-sex love is struck down by the Indian Supreme Court. Is this one of life’s loving ironies?

And then comes something even more powerfully ominous. The fight over Sabarimala temple, and the sweetly innocent idea that you can ensure male monastic celibacy just by keeping menstruating women out of your world. That sex – and sexual temptation – is synonymous with women. How cute is that? The Scent of God, too, ends up narrating the fragility of that notion, and how it shatters into the shards of a saffron rainbow.

From The Scent of God:

Don’t fight it. The Lotus said.

Slip out of it like you slip out of your shirt. Watch it play, a cheap toy. Slowly, the mind will become your slave.

The Lotus, he knew, could do anything. He could be like Arjun. Arjun shut out the rest of the world, fixed his gaze on the wooden bird on the tree, and shot its head off with his arrow. The carrom striker became an arrow in Kamal Swami’s fingers. The red monster shot at the circle of coins at the heart of the board and ripped it open, sending a cluster of the right coins to the pocket. It was like a blast of dynamite.

Anirvan felt terrified to see the explosive force stored in the smooth, saffron-robed monk. But if you controlled your mind you controlled the striker. Kamal Swami, he knew, could stare hard at a coin so as to make everything else vanish from his vision. And then destroy it. Kamal Swami. The Lord Lotus.

Meditation was a skill crucial to life in the ashram. It sharpened your mind, helped you master algebra, geometry and physics. Everything one needed to crack the engineering entrance tests. The boys stared at the tests, five years down the line, and tried to make the rest of the world vanish. How do you think the ancient Indians invented the zero and other foundations of mathematics? Kajol always said. And he cracked the puzzles of geometry so smoothly that it seemed that he felt the problems and the answers like tremors in his own body. His lovely bony body.

How do you think? Because yoga is the foundation of mathematics.

Yogi. Kajol fell in a kind of a spell whenever Anirvan meditated under the shower. Sometimes when Anirvan’s mind wavered, he could feel Kajol’s liquid stare on his skin. Sometimes Kajol would touch him lightly and Anirvan’s focus would shatter. Yogi. Kajol called him Yogi. The one who has mastered Yoga. One who controls his mind like a steel toy. It became his name. No one remembered Anirvan.