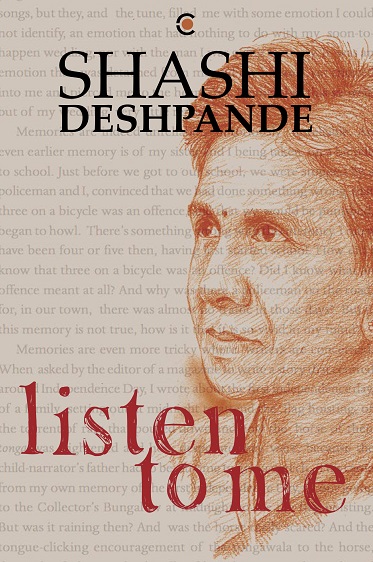

Shashi Deshpande has had a long and rich career as a writer of novels, short stories and essays. In her literary memoir, Listen to Me, published by Context, an imprint of Westland Publications, she traces her development as a writer. Touching on the personal circumstances of her life, the places she has lived in, and the languages she has heard and spoken, she addresses the central question of a writer’s sensibility – a writer who is a woman, and a writer who has known many Indias, past and present. Extracts from Deshpande’s memoir and a conversation with writer Githa Hariharan shed light on her work over several decades.

Githa Hariharan (GH): Your memoir is preoccupied with location in many senses of the word. So is your other writing. In the memoir, you take us from the Dharwad of your childhood, to a changing Parel, to both old and new Bangalore, and the houses you have lived in. Would you comment on this continuous process of defining your home?

Shashi Deshpande (SD): I have always had a very strong attachment to places. I lived in Dharwad for only the first fifteen years of my life, but it has stayed with me through the years. So has the ancestral ‘wada’ of my mother’s family in Pune, which we visited every year in my childhood days. Some years after my marriage, the ‘wada’ was demolished, but it still lives with me, inside me. As do the hospital quarters in Parel, Bombay where my children were born and grew up and the quarters in NIMHANS where they moved into adulthood and left home in pursuit of their own careers. But above all each place contributed to my growth as a writer. From Dharwad, where I became an ardent reader, thus laying the foundation of my writing, to Bombay where, first as a student, and then as a married woman, my experiences and observation of the life around me shaped my thinking, to Bangalore where I recognised that writing was my life’s work and settled down seriously to it — each place has played a role in my writing life.

But I consider Bombay the place that made me a writer and shaped me as a writer. It was this phenomenally active and bustling city which never sleeps that set my imagination alight. It was the women who came to work for me, who gave body to this imagination. They invariably had drunken husbands – why would they go out to work otherwise? – and were almost always victims of domestic abuse. I saw how hard they worked, how unflinching they were in their determination to see that their children had an education, that ‘my daughter should not become like me, she should not live the kind of life I do’. Their hard lives, the way they coped with cruelty, made me understand, a girl who had lived a sheltered life, the injustices in life. It was this understanding that pushed me into writing – so I like to think now.

GH: But beyond place, you also address the rich but slippery living a life with many languages.

SD: Yes, there’s also the fact that when I came to Bangalore, I relocated myself in the language in the midst of which we had lived when we were in Dharwad. In Bombay, I was familiar with Marathi, but it was only the language in the family. Here, in Bangalore, Kannada was spoken all around me, we saw Kannada films, Kannada plays, heard Kannada songs. Through my father, I came upon the world of Kannada writers, of Kannada drama. And the world of Purandaradasa and Basavanna, whose songs my father chanted tunelessly all the time, so that I unconsciously imbibed some of their words, preparing myself for the time when I would read them on my own. I realised then that I was part of this world. It gave me a rootedness which I, as an English writer, had lacked until then. For if my writing language was English, the world of my two languages – Kannada and Marathi – was where my writing was located. My connections to the cultures of these two languages were very strong and my writing reflected this. Yes, Bangalore dispelled that sense of not belonging, or of not belonging entirely, to any place. In A Matter of Time, Small Remedies, Moving On and In the Country of Deceit, I returned as it were to the world into which I had been born, easy and comfortable now in that world, the language in which I wrote becoming naturally a part of it.

From Listen to Me:

There was a time, I remember with some embarrassment now, when I had said that my influences were the British writers, specially Jane Austen, the Brontës, George Eliot, Mrs Gaskell, Dickens and so on. Yes, it was from these writers (and others as well), that I had learnt about the amazing grace, beauty and strength of the novel, just as I had learnt from the Russian writers about passion and intensity. It was as a reader that I had imbibed from these writers an understanding of the use of language, of narrative structure, which were to stand me in good stead as a writer. Nevertheless, I would soon understand that this was not where I came from. I read F.R. Leavis’ The Great Tradition when I was doing my MA, and found this statement right at the beginning: ‘The great English novelists are Jane Austen, George Eliot, Henry James and Joseph Conrad.’ Leavis also says, ‘Jane Austen is the inaugurator of the great tradition of the English novel.’ While I marvelled at the certainty with which he said these things, his statements made it clear that Indian English writing had no place in the literary world he was speaking of. A common language was just not enough. My visit to London, where I was classified as an Indian writer, as an Asian writer, and later, my visit to Cambridge, made me understand how far removed I was from the British tradition.

However, in time I began to understand that I did not come out of emptiness, but from a far more complicated place. I had three languages – my father’s language, Kannada; my mother’s, Marathi; and the one that became my own, English. I read some more languages, including Sanskrit, in translation. As children, our father made us learn the Amarkosa, a kind of Sanskrit Thesaurus, by heart (I can still quote some lines). I absorbed, like all Indians do, the myths and legends, stories from the epics and the Puranas, along with fairy tales and English children’s books – from Little Women, What Katy Did and Heidi to Treasure Island and Alice in Wonderland. In later years I read, again in English translation, the Ramayana and the Mahabharata and, much later, the Gita and the Upanishads. As a girl, I read stories in Marathi women’s magazines along with stories in Woman & Home.

I was exposed at an early age to the devotional poems of Purandaradasa and Basaveshwara, through my father’s love for and knowledge of these poems. I listened to Marathi natya sangeet in my mother’s Pune home and to abhangs and bhavgeets in Marathi. I saw and thrilled to the spectacle of the Yakshagana, I loved the beat of the staccato music and loud singing that accompanied the dancing and the dainty mincing steps and gestures of the dancers, which were at such variance with their large grand costumes and garish make-up. I responded with fervour to Mirabai’s poems, especially when sung by M.S. Subbulakshmi, I enjoyed Hindi film music, adored Geeta Dutt (oh, her Mera sundara svapana beet gaya!), and found Hollywood movies satisfyingly exotic. I enjoyed the romance in Bhasa’s Svapnavasavadatta as much as I enjoyed Daphne du Maurier’s Frenchman’s Creek. In personal life, I knew I was a Hindu (though, as our father’s children, we were never overly conscious of it), but studying in a Roman Catholic school had made me familiar with the church. We entered the church, dipped our fingers in the holy water, genuflected, knelt, knew how to recite Our Father who art in Heaven and Hail Mary full of grace. As a grown woman, I visited the Ajmer Dargah, as well as the Church of Infant Jesus. There was never any sense of conflicting contrary selves; everything was harmonised and melded into one. Like Walt Whitman, I could have said: ‘Do I contradict myself? Very well then, I contradict myself. I am large, I contain multitudes.’

And yet, when I was writing my second novel, The Dark Holds No Terrors, I knew what not belonging meant. It meant I was entirely on my own, it meant I had no predecessors in whose footsteps I could follow, it meant I had to write solely out of myself, creating and shaping a language to meet my needs. Peter Ackroyd, in his biography of T.S. Eliot, speaks of Eliot complaining to Virginia Woolf that, ‘in the absence of illustrious models, the contemporary writer was compelled to work on his own.’ The illustrious models were even fewer for women. And for an Indian woman writing in English, for the kind of writing I was doing, the lack of any kind of model, illustrious or otherwise, was even more evident, the lack of a safety net of other writers’ work, which Ackroyd says Eliot needed, even more glaring. In fact, I wrote out of a blankness which had only myself in it, out of a large silence which I had to fill with my words. Words, which I had to discover, to conjure out of thin air, for there were no models for me to follow. Indian writing was in the Indian languages and English writing was done by writers whose language it was the way it could never be mine.

Nevertheless, it was a good time to be a part of Indian writing in English. Indian writing in English was on the brink of a great change; very soon this writing would become known and read through the world.

GH: You raise the question of politics in the novel, and indicate that this refers to any sort of probing of power structures, including in the family. This enlarges our understanding of the political, and brings into play the principle of the personal being political. Would you say gender, rather than caste or class, is the main prism through which you view power politics?

SD: The family is a microcosm of society and the same power politics that exists in society is in play in the family as well. Power politics begins in the family and it is gender that separates the powerful from the powerless. I remember reading a report which came out after the World Conference on Women that women workers are the most poorly paid everywhere in the world. That however poor a man is, a woman is always poorer. She is at the bottom of the pile. It substantiated my idea that all women, whatever class, religion or even caste they belonged to have been deliberately, from times immemorial, been deprived of power, over their own bodies, over their own lives.

As a writer, I often felt at the receiving end of this idea that women being less important, their lives are not important, ether. That women who write about women confine themselves to the family and home. I remember in my early days as a writer an interviewer asked me that since I wrote only about ‘in here’, and not about ‘out there’, did I not feel circumscribed, limited? And I had to think what ‘in here’ and ‘out there’ meant. I then understood that I could not think of them as two rigidly exclusive categories, one more important than the other. Think of Tolstoy’s War and Peace without the Peace, or the ‘in here’. Of Tagore’s Home and the World without the Home. Like the world, home was equally a battleground in which injustice was rampant. Home was the first place where the inequalities, the injustice began. Home was where girls and boys learnt the truth and the reality of patriarchy. Reading cases of divorce, separation and custody of children for my novel Shadow Play I came across a sentence ‘The categories of cruelty can never be closed’. The most chilling words which gave me a glimpse of the world of cruelty which can exist within the home and the family. A cruelty which is always concealed and kept within the walls of a home, not spoken of. And therefore more dangerous and harder to fight.

It was some time after I wrote That Long Silence that I realised that this book was about the politics of gender. About the belief held, for perhaps all the years since human life began, that in the family the man is the master and the women (and children) are his subordinates. By chance I came across Engel’s The Origin of the Family, Private Property and the State and found in it this statement: In a family he (the man) is the bourgeois, the woman represents the proletariat. And this one: The first class oppression is that of the female sex by the male.

That Long Silence was not written to substantiate these statements. I wrote the novel before I read these words and it seemed to validate these statements – to my mind, at least. And yet, to the literary world, That Long Silence and all my subsequent novels were just ‘women’s novels’. Which immediately put them in a small frame. Not even a miniature, which has a beauty of its own, but just a novel about women set in the family. The personal, not the political. Trivial and insignificant as compared to novels which were ‘out there’, set in the large frame of the nation, of the world. Novels which could aspire for the description ‘epic’.

I do not want to dramatise myself and say that my whole writing life has been a struggle against this idea; but I have to say that to go on writing despite the way my novels were received, labelled, categorised and put in their place, was never easy. Yet it was possible, because of my own belief in what I was writing, my certainty that my novels were about women’s struggle to understand what they were, beyond the stereotypes they had been made to believe in. A class struggle has some validity, it is taken seriously. A woman’s struggle against whatever is stacked against her is never a serious struggle. Even today this has not changed. Not completely.

From Listen to Me:

We are all very early risers in our family. For this reason, and also because in those days telephone calls were cheaper late at night and in the early hours, my sister and I had got into the habit of speaking to each other as soon as we woke up. Therefore, I knew when the phone rang one morning even before we had had our early morning tea that it was my sister, though, perhaps, it was a little earlier than usual. Her voice, too, was different and she began abruptly without any preliminaries.

‘She’s gone,’ she said.

I didn’t need to ask whom she meant, because we’d been talking a great deal about her the past few days.

‘When?’

‘Three in the morning,’ she said and put down the phone. I knew she could not talk any more because she was crying. So was I. Why did this young woman’s death hit us, and so many others, so hard? For days we had watched the protests and the demonstrations on TV – women, men, girls, boys, young and old, all coming together on behalf of this dying girl. After her death, the protests intensified, the anger could barely be controlled, though the crowds were never violent. The police, however, didn’t hesitate to attack the protestors with lathis and water jets. An indelible image of those days for me, is of a young woman being knocked down by a policewoman and lying still on the ground for a moment, her face registering her shock and disbelief. And then, springing up, and throwing herself at her attacker with a ferocity that took the policewoman by complete surprise.

What had brought about this upsurge of support for one young woman from so many people all over the country? Except for Anna Hazare’s anti-corruption movement, which sadly fizzled out, I could think of no people’s movement that had been as spontaneous and powerful, in the last few years. One of the reasons was, perhaps, the ugliness of the crime committed against her. It was not just rape, but gang rape, accompanied by an indescribable bestial cruelty. The girl’s friend had been forced to watch what was being done to her, and after the four men were done with both of them, they had been thrown out of the moving bus, in which all this had happened. Thrown out on the road, as if they were trash for which these men no longer had any use. Part of the huge sympathy for the girl also came out of admiration; she had fought back fiercely, she had not given in. Even afterwards, when she was in hospital, she gave her dying declaration to the authorities, twice, in spite of the terrible state she was in. The sympathy partly came out of the persona of the girl herself, a girl who came from a rural area, from a family in very modest circumstances, and who was, with her own efforts and her parents’ support, trying to move into a career and a better life, both for herself and her family.

But let me call the young woman who died by her name: Jyoti Singh. The media, in accordance with the policy of not naming a rape victim, spoke of her as Nirbhaya. They continued to call her Nirbhaya a year after her death, when Jyoti’s parents and many others were agitating for a quick trial and maximum punishment for the rapists. It was then that Jyoti’s mother, a woman of great dignity and courage, said, in response to a journalist who spoke of her daughter as Nirbhaya, ‘My daughter’s name is not Nirbhaya. Her name is Jyoti Singh.’

It was, so I think, a moment of great significance that marked the end of an era. An era, which considered that rape shamed the woman, not the rapist. More than two decades earlier I had written The Binding Vine, a novel that had come out of another rape, the rape of a young nurse, which had also sparked off public outrage. In my novel, the mother of Kalpana, the rape victim, insisted on not letting the world know that her daughter had been raped. And now, here was this woman saying, ‘My daughter is Jyoti Singh.’ I felt the goose bumps come up on me when I heard those words.

I have always considered rape to be one of the worst crimes that a human can commit against another. Lust-driven, yes; a violation of a woman’s right to her body, yes; an assertion of male power, yes; of a male’s right to possess the female body, yes. But more than these, and above all these, it is an expression of contempt and hatred for all women. The barbaric and savage things that had been done to Jyoti had filled everyone with horror and anger. This most intimate act between two humans – an act that expresses love and tenderness, and a desire for a complete union with another human being – how could it become an act of such violence and cruelty? How could anger and hate fuel an act that is supposed to be driven by love and desire? Rape can also be, and often is, a political act. I can never forget how shaken I was by a hard-hitting poem, written by a Marathi poet Neeraja, about two rapes. One, a rape of two Dalit women, a mother and daughter, who dared to stand up against upper caste pressures. The rapists were Maratha (upper caste) men. And the other, a rape by Dalit men of a young Maratha girl. Both the rapes were later used by the victims’ communities for their own political purposes, used to show their strength, their power. As Neeraja’s poem From Khairlanji to Kopardi says:

‘You have pushed your political ambitions into her body/ fought battles and defeated your enemies/by playing the game between her thighs.’

Equally bad were the comments that came, after the outcry against Jyoti Singh’s rape, from males from all over the country, especially politicians and those in responsible positions, blaming women themselves for rape, saying that women sent the wrong signals by the way they dressed/behaved/went out in the evenings/ spoke on mobile phones, etc. And therefore, when he was so provoked to lust by these things, what could a poor man do? ‘Boys will be boys,’ one national politician famously, or rather infamously, said. These statements too smacked of hatred of women. Men spend some of the best moments of their lives, some of the most tender moments of their lives, with women. So, where do these statements come from? Where does the hatred come from? And how can we expect men, whose minds are dark pits of such ideas and thoughts about women, to pass any laws which benefit women? Why would they pass a law which would allow women a proportional representation in Parliament? And I thought, a bleak thought, if neither laws nor society changed, what hope was there for women?

GH: When the Sahitya Akademi did not respond to the assassination of M.M. Kalburgi in 2005, you resigned from the Akademi’s General Council, saying, very powerfully, that in such a situation “silence is an abetment”. Would you revisit that moment for us?

SD: The death of Professor Kalburgi pushed me to a point when I realised I could no longer be silent. If the silence of the Akademi was an abetment of Prof Kalburgi’s death, my silence would also be an abetment. I had to speak. And it was you, Githa, who gave me the courage I needed.

GH: You have all the courage you need, Shashi.

From Listen to Me:

The BJP government, which came to power with promises of development and progress, seemed to embolden certain fringe Hindutva elements who went on a spree, trying to impose a dubious idea of ‘an ancient Indian culture’ on the country, ignoring our long and glorious history of multiculturalism, of many religions living together. These culture-defenders decided what was right and what was wrong, they made their pronouncements on what could be done and what could not be done. But even worse was to come. Three men, two of them rationalists who were intent on eradicating superstition, and one of them a scholar, were killed. The scholar, Prof. Kalburgi, was shot dead in his own home by a man who came on a motorcycle, rang the bell, and shot the Professor when he came out to greet a supposed visitor. (Most strangely, the day I am writing this is an anniversary of his death and the murderers have not yet been traced.) Prof. Kalburgi had been threatened before for writing something about Basaveshwara, the man who broke away from Hinduism because of its caste system and the inequality that it created. He had unearthed some facts about Basaveshwara, which the custodians of Basaveshwara did not like. At that time, the Professor had retracted from what he had written, but he had not stopped his research.

When I saw the news of his killing on TV, I was shocked. I had met him earlier, when he had been the Vice Chancellor of the Kannada University at Hampi. My sister and I had contacted him in connection with our desire to give our father’s manuscripts to the university. He had been courteous enough to come home to discuss this. I met him again later at the meeting of the newly constituted General Council of the Sahitya Akademi to which I had been nominated as a member. Prof. Kalburgi was a member as well. He was a soft-spoken, gentle man. That such a man had been shot, and in Dharwad, which had always seemed to me the most civilised of towns, was hard to believe. I expected the Akademi to say something about his death, to put out a statement, perhaps, condemning the killing, expressing their grief at the loss of a writer, a writer who was a part of their organisation. Nothing happened. The silence made me uneasy and I wondered whether there was a reason for it. I then heard from a friend that the Akademi had held a condolence meeting in Bangalore, during which no mention had been made of the fact that he had been murdered; they spoke of his death as if it was a natural one. I could not believe this. I was haunted by an uneasiness I could not pin down.

Then something else happened. A Muslim man was killed on the suspicion that he had eaten beef. To my great surprise, and even greater pleasure, two writers, yes, writers, Nayantara Sahgal and Uday Prakash, stood up to protest against these happenings and as a protest returned the awards the Sahitya Akademi had given them. Now my uneasiness congealed into a resolve: I could not be a part of an institution which did not stand up for the writers it was supposed to represent. The Akademi, I thought, had failed writers. I made up my mind to resign from the Akademi.