Char island.

The hurricane sucks you under,

spews you out in a heaving deposit a hundred miles away.

A tidal mass of breakers all around – crashing, foaming,

waiting

to sweep you up again, to throw you around

like an impermanent offering

to the river goddesses:

a different form, a different shape

for a different appetite;

shifting silt islands that do not hold nor satisfy

the insatiable appetite of goddesses who course

towards the sea,

dark,

hungry,

raging.

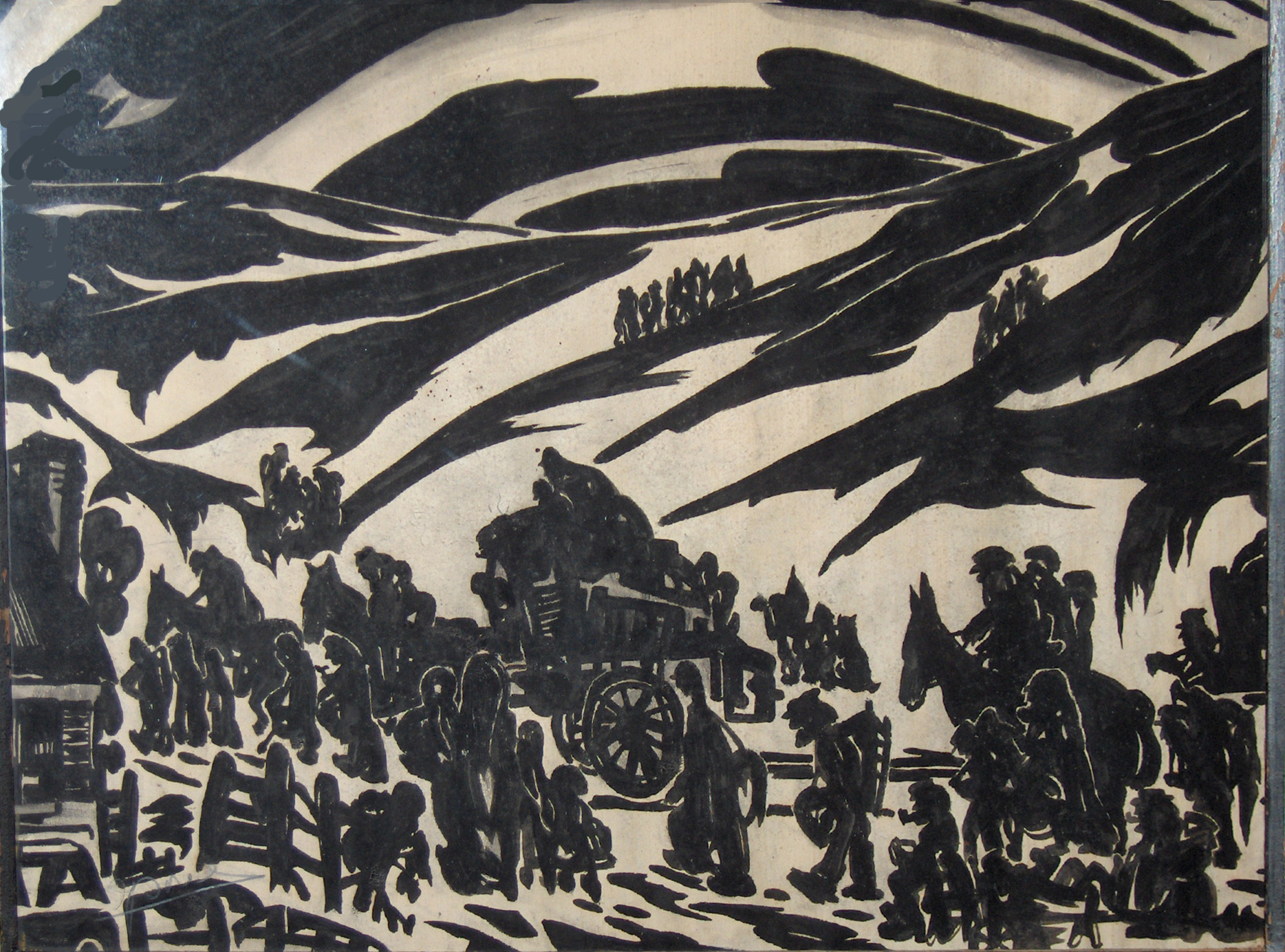

His sixth poem written during his third sleepless night in a row. He knew from the stories of his ancestors that char islands with their alluvium deposits from overflowing rivers could be so fertile that three crops could be raised in a year, if not ruined or drowned by storms or hurricanes. Fertile, fertile as his euphoric mind, when euphoric. He could feel the drumbeat in his head like a beep light — bright, incandescent, alert — sending out signals he had no control over. Like the alarm of a car backing up, its high decibels beeping out a warning to stay out of range. He had to write then, more than ever — as if his skin, blood, glands were all focused on the words, spilling out with a life of their own. Words not much better than in normal times, not brilliant — just needing to be out in a spill of euphoria, like motes of dust in a shaft of sunlight — dancing, dancing. His whole body felt light like air. He must drive, drive fast, meet the air outside, feel its lightness like the lightness of his being. Lightness mingling with lightness, skin on tremulous skin.

He slammed his laptop shut and got up heavily from his chair. He saw the vase flying from his desk — heavy and green, a bunch of artificial roses still snugly held in its cylindrical womb. It landed near his foot — the vase in four pieces, the roses spilt, serrated leaves green and plastic. The tic in his eye first made a tentative appearance, twitching sporadically, then steadily. He must go out, drive, before this took over, this heavy nervousness. Mariam entered the room, flinging the door open. She took in the scene, her face tired, expectant.

Though heavy, she moved lightly, with nervous energy. Her flowered night gown hid her corpulence, and her struggles that swung between feasting and fasting. Flecks of henna hid the gray in her hair, blending copper into thick dark waves. The remnants of a pink polish stuck crustily to her chewed nails, now clipped neatly. Her puffy face, lined with sleep looked strained as if sleep did not refresh. She looked at the pieces of broken vase, deliberately moving her gaze away. Her eyes straying to the open window framing the orange of dawn suddenly prickled with tears. She ignored them as she moved to sit at her husband’s desk, keying in the laptop’s password. Hasan stared at his wife with his twitching eye. No screams today. Today was the ice maiden day. Following psychiatrist’s orders: don’t invite conflict during mood swings, let the manic depression ride out; he has both individual and family psychotherapy as support, he has prescribed medication as support. He is a writer, a well-known writer, don’t stem his creativity. Let the mood ride out. Let the mood ride out. That is the support you can provide.

Hasan watched her read his output of the night, her face set in lines of self-control, as if she would rather scream or clean up the vase. He valued her opinion of his work. Perhaps because she was an artist and taught sculpture in a senior school, she instinctively knew craft — equally the craft of a sculpture as of a poem. He also knew something of her creative expression in her group therapy sessions with the spouses of other manic depressives. They walked along the beach at dawn, sang songs they knew or made up, spoke to the sea about their issues, to the sand, to each other. He looked down at his pajamas, surprised that only a few minutes ago he had wished to take a fast drive through the empty streets to merge into a lightness he no longer felt.

“These are fine, Hasan,” she said unsmilingly. “Char islands, changing borders, shifting populations… migrations, this is all fine. But this all happened a long time ago, more than a hundred years ago. You are not a migrant, you are settled. Try to feel that within. Settled. Not persecuted, but settled,” tapping her heart. She stumbled lamely out of the chair and stared at the broken vase. “Remember to take the anti-depressant after breakfast. You know where the carpet brush is. See if you can clean up this mess.”

Hasan stared at her retreating back. A few minutes later, he heard her car door slam in the narrow driveway as she made off for therapy. He waved from the window but she did not see. She was intent on backing out.

When Mariam reached the beach, the sun was an orange orb rising out of the sea, burnishing the grey waves in wide ripples of gold. Gulls flew low above the water, wingtips tilted at right angles to the sea.

Philip, their therapist was there already in his grey track suit, grinning as he jogged on the smooth wet sand, his shoes leaving patterns on the beach. Vera, in her late twenties, greeted Mariam with a nervous smile, a nervousness Mariam recognised as her own — both having volunteered to present their issues this morning. Soon they were joined by the others — Rashmi, Arun and Steven — the group walking slowly on the sand towards the site of the fishing boats tethered to the massive black rocks. Vera chose a spot where the group could squat, the sand dry and loose beneath the circle they formed.

Philip waited for the small talk to die down, then smiled at Vera. She flipped agitatedly through the pages of a book covered with newspaper, her tight curls bent studiously low. I am going to read a poem by Sylvia Plath, she said. It’s called ‘Mad girl’s love song’. Sylvia was a college student when she wrote this, obsessed with finding true love. Two years after writing this, she attempted suicide. She swallowed her mother’s sleeping pills and crawled into a hiding space for three days. She tried suicide other times too. Finally, she put her head into an oven and gassed herself to death. She was 30.

“Mad girl’s love song”, read Vera tremulously but without pausing.

I shut my eyes and all the world drops dead;

I lift my lids and all is born again.

(I think I made you up inside my head.)

The stars go waltzing out in blue and red,

And arbitrary blackness gallops in:

I shut my eyes and all the world drops dead.

I dreamed that you bewitched me into bed

And sung me moon-struck, kissed me quite insane.

(I think I made you up inside my head.)

God topples from the sky, hell’s fires fade:

Exit seraphim and Satan’s men:

I shut my eyes and all the world drops dead.

I fancied you’d return the way you said,

But I grow old and I forget your name.

(I think I made you up inside my head.)

I should have loved a thunderbird instead;

At least when spring comes they roar back again.

I shut my eyes and all the world drops dead.

(I think I made you up inside my head.)”

Vera smoothed the book’s paper cover with a hand that moved back and forth rapidly. When she spoke, her voice was a moan, “There is no love — real or dream. It’s all shit — alcohol shit, depression shit, poor me shit.” Tears streamed down her face falling onto the book, blurring the newsprint where they fell. “You think there will be stars — blue and red ones — but it’s blackness that rushes in, gallops in, that’s true. You sleep, shut your eyes, feel it’s all gone. Open them – it’s all there, the shit.

Philip waited for the tears to abate. “This was one of Plath’s favorite poems,” he said. “I have read it several times. Many people read it and think Plath is writing about her own battle with depression. But the title could simply refer to the madness that takes over a young girl — an ordinary young girl — who yearns for love but doesn’t find it in reality. It happens to many people.”

“What’s seraphim?”, asked Rashmi, her large eyes following a fisherman pushing his boat out to sea.

“A seraphim is an angel of the highest order — full of light and purity,” volunteered Steven.

“Yes. But it’s not as if the seraphim — this high-level angel — leaves alone. So do Satan’s men. And if God topples from the sky, hell’s fires also fade. Once everything is null and void, anything can happen,” said Philip.

“Anything can happen. But nothing does,” said Vera. “This madwoman even longs for a thunderbird to return in spring. There is no thunderbird. A thunderbird is a myth. Please, let’s not discuss this anymore. Please. Let’s hear out Mariam. She may bring in more real things than thunderbirds.”

Mariam felt the sweat gather in her armpits and roll leisurely down her sides, one line moving slower than the other. There was no sea breeze — just the steady sound of lapping waves. Philip looked at her enquiringly. Mariam let her gaze wander to the fishermen’s boat moving steadily over the tides, receding. Could these men ever be fully prepared?

“I had a dream last night which I want to share,” began Mariam. There was a long pause. “I am on a remote island with Hasan. It is crowded with people who are very agitated. Some men are waving documents in the air which they don’t know how to read. It is very dark. Hasan offers to read somebody’s document by the light of a petromax lamp. It is a notice to appear by the morning in a court far away — with documents. A woman wails that she has seen a massive detention camp being constructed deep in the forest. There is a scramble to assemble family members. Both men and women hold papers to their chests in bright plastic bags. They scream with fear as they jump onto small rowboats to cross the rushing river. It is pitch dark. Hasan and me scramble onto different rowboats and are separated. People are calling to each other with words like ‘voter cards’ and ‘refugee certificates’. The boats bob on the stormy river like corks. Suddenly I am in a pick-up truck. Hasan is with me with the same bright plastic bag as the others. Our truck crashes into another truck carrying barrels of tar. People are flung on the road and covered with tar. I hear Hasan groaning. He is crawling, searching for the plastic bag. He is covered with tar. His tears shine on his face against the black. I try to remove the tar from his searching hand. All I can peel off are a few pebbles. The tar sticks.”

The sea breeze picked up, blowing about the debris on the sand. Her body chilled, Mariam fixed her clouded gaze at the boat, now a dot on the sea’s horizon. Her tears flowed, warm then cold on her face. “I guess it’s difficult to get tar off, isn’t it?” she said through a wan smile.

“You didn’t mention — were you also covered with tar?”, ventured Philip, tentatively.

“No,” laughed Mariam, shaking off her tears with surprise. “I had no tar on me. There was tar everywhere but where I fell there was no tar, only a terrible pain.”

Eyes closed, Steven spoke hesitantly as if trying to remember the words of a psalm, “The Lord is close to the brokenhearted and …and…binds…”

“…saves those who are crushed in spirit,” offered Philip.

As the sun rose higher, the group, now silent and reflective, rose to walk back together in a close huddle like a single body-formation buffeting the wind.

Hasan waited for Mariam to return knowing she would be more empathetic with his depression than with his euphoria. His body was slack in his chair as he watched through a haze the cleaning woman sweep the room, stopping for a long moment where the broken vase lay… broken sandbars in the river appearing disappearing with the river’s moods. Masters in the art of farming, we knew the silty river plains, the shifting islands of the river… the river was ours too from across the border from where we came. Rivers joined, country borders separated. We were peasants but came as invitees of the British. They gave us lands to cultivate for they knew and we knew our produce would fill their coffers. We came in thousands, felled forests, turned marshes into farmland. River plains and islands blossomed. In our adopted homeland, we adopted the language spoken as our own. We were accepted, we were happy.

Hasan barely noticed the cleaning woman leave after having stared at him a long moment. She had picked up the empty glass from his side table, sniffed at it, had smelt the alcohol with distaste.

He thought Mariam would never know nor understand what it feels when a tree puts down roots in new soil but will not be accepted by it. Why? Because borders change, soils change, flux flux, flux… minority becomes majority, majority becomes minority. Partition brings influx, war brings more influx. Millions enter without invitation, from fear of dying otherwise. Cities grow, forests fall, marshes fill, tribal commons are swallowed by development. The fissures grow old, hard, cruel. The 3 D call beeps loudly: Detect, Delete, Deport. It doesn’t matter if you are an old settler or relatively new. It doesn’t matter if you can prove yourself a “genuine Indian” with “legacy papers”. Nobody wants you. Nobody. Not the state’s nationalists, not the center’s nationalists, not the tribal, not the religionists. No one. So many already in detention like common criminals. Am I happy being declared a “genuine Indian”? No. So many settlers like me left out. Arbitrarily. Where will they go? To tribunals for redressal where the judges don’t want them? To detention camps? Stripped naked of citizenship? Deported? Deported where? Oh, mother where will we go? Where? Surely, we have seen enough killings, arson, bomb blasts, demonstrations declaring us “outsiders”? Surely…?

Hasan’s eyes closed and he slept as if in a stupor. When he woke, he saw the room was dark except for the soft light of the table lamp on his desk. His head felt clear. He held up his hands. They were steady. He walked out of his room to peer into the passage. Mariam’s bedroom light was out, the house was in darkness. He opened the casserole on his side table but decided he was not hungry. He sat for a long while at his laptop, then typed:

Char islands – alluvium of your overflow,

hostage to your monsoon rage

breathe easily in winter as you flow – smooth

serene to the sea.

Char islands, charred spirits…

I know your rage, Mother.

I also know your winter grace

to be a chimera.

Do you not flow through this land and the other

from where I first came?

If you belong to both, so should I.

Should I not, Mother?

Then why don’t I belong?

Why am I made again and again

to prove myself – my roots, my belonging

through papers not through spirit?

Why…am I hated, reviled…

Hasan stopped. He lurched towards his bed, fell face down and moaned. Sleep came to him quickly, greedily.

When he woke, it was fully light. He felt the fragrance of Mariam’s perfume in the still air of the room. The table lamp had been switched off. His laptop was still open. He stumbled wearily towards it, his head unclear, his mind anxious. He pressed the Escape button. The screen blipped open to his poem. He read:

Char islands, charred spirits…

I know your rage, Mother.

I also know your winter grace

to be a chimera.

Do you not flow through this land and the other

from where I first came?

If you belong to both, so should I.

Should I not, Mother?

Then why don’t I belong?

Why am I made again and again

to prove myself – my roots, my belonging

through papers not through spirit?

You are both rage and grace, mother.

I give you my hurts, my searing wounds

Just as they are – open and festering, Mother.

Take them into your womb, take them… and hurl them into the sea.