In India, printed Urdu literature and Urdu language have recently been associated with Muslims and Islam, often assumed to be reflecting religious orthodoxy and austere iconoclasm due to an apparent absence of images, or at least the images of human figure in its contemporary printed examples. Furthermore, the ignorance about Urdu’s eclectic and celebratory past is often so acute that in a recent example, couplets of 19th century Urdu poet Mirza Ghalib were attributed by Mumbai Police as inciting hatred and terror.1 But this one-sided stereotype of Urdu may not necessarily be a construction of the non-Urdu people alone. Even many ‘Urdu-wallahs’ or Muslims consider it not only their language but also a symbol of their religious identity rather than a shared cultural entity. A handful of Urdu speakers though do make an effort to deter this identity myth.2

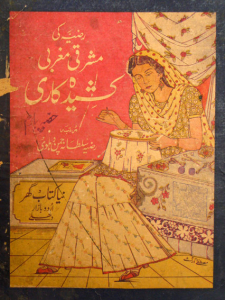

Razia ki maghribi mashriqi kasheeda kaari (Razias eastern-western embroidery), cover of an embroidery book published by Naya Kitab Ghar, Delhi, Circa 1940s.

Razia ki maghribi mashriqi kasheeda kaari (Razias eastern-western embroidery), cover of an embroidery book published by Naya Kitab Ghar, Delhi, Circa 1940s.

This typecasting about the language however did not always exist in India. Urdu language or script was the most common medium of mainstream communication, especially at the time when print culture began thriving in north India. While today’s Urdu printed literature such as books, magazines or other ephemera may reflect a lack of liberal visuals or artistic creativity, probably due to a decline in its readership, Urdu printed ephemera in early 20th century or before was the main carrier of ideas, news, business and education, with a large pan-India readership that was not restricted to Muslims alone. Its popularity can be gauged by the fact that Urdu magazines carried advertisements of almost all mainstream trade brands just as today’s major newspapers or magazines do. Most importantly, the advertisements and the illustrated features in popular Urdu periodicals were not restricted in any way about the depiction of culture, arts, cinema, glamour, and women etc. In fact, these were as liberal and celebratory as any mainstream magazine today. They also catered to the religious or cultural needs of Hindus and other communities as much as they did to the Muslims. Similarly, Urdu was one of the first Indian languages in which progressive ephemera such as greeting cards, calendars and business stationary etc. were printed and used widely.3

Soon after India’s independence in 1947, however, one witnessed a decline in Urdu’s print culture, primarily since Urdu was removed not only from being a medium of education but even a subject in most schools in north India, mainly in Uttar Pradesh, which ironically was its birth place and natural home. In short, the entire subsequent generations were schooled without an essential language and script that their immediate ancestors were familiar with.4 Naturally then, the first thing to be affected was Urdu’s connection with mainstream media, industry, politics, and professional lives of people. Slowly, as the Urdu-literate generation dwindled, so did the liberal and inclusive image of the language and its printed literature. And today, much of Urdu works published in India are restricted to religious themes or the issues of Muslim community alone, and that too bereft of any liberal visual depictions. Through this short visual essay, the author would like to explore what caused Urdu to be gradually associated only with Indian Muslims even though its early print culture was not restricted to Islamic or Islamicate themes and was a more inclusive media for mainstream secular communication.

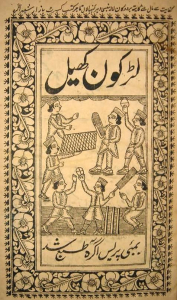

Ladkon khel, a chapbook about boys’ games. Published by Bambai Press, Agra. Undated, possibly circa 1890.

Ladkon khel, a chapbook about boys’ games. Published by Bambai Press, Agra. Undated, possibly circa 1890.

Urdu played a crucial role in almost every sphere of north India’s intellectual life in 19th century. It emerged not only as a language of courtly poetry but also of popular prose, to spread religious values, for the moulding of public opinion, and for the transmission of knowledge and education. In 19th century there was a boom in commercial publishing, not only to cater to the elite among Urdu and Hindi readers but also the neo-literate non-elites who had so far not accessed the written or printed word. According to Francesca Orsini, a large repertoire of popular literature such as detective novels, theatre transcripts, songbooks, saint biographies, serialised narratives, and popular poetry, printed on cheap paper, provided an activity of pleasure for thousands of new readers.5 Moreover, for those who see Urdu and Hindi today with two distinct identities, this early print culture also reflected a considerable hybridity and fluidity between the two languages. In the ‘commercialisation of leisure’, according to Orsini, the boundaries between Urdu and Hindi had somewhat collapsed. Obviously, much of these chapbooks also contained attractive illustrations, some on the book covers while many printed inside, such as those depicting characters or scenes in the works of fiction, often in the tradition of the older book manuscripts. The title of many of these books contained the word ba-tasveerat (with pictures) to attract the buyers. Some of the famous publishers of such illustrated Urdu literature were Matba’ Naval Kishore from Lucknow besides others in Delhi, Kanpur and Lahore. Naval Kishore Press, in fact, was the most prolific publishing house that brought out a large number of titles in Urdu, Hindi, Arabic and Persian.6

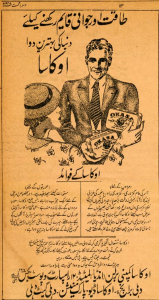

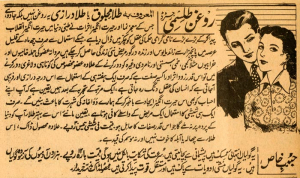

European looking man and woman in an advertisement for Okasa, a health drink. Printed in an Urdu magazine, Mumbai, 22 August, 1937.

European looking man and woman in an advertisement for Okasa, a health drink. Printed in an Urdu magazine, Mumbai, 22 August, 1937.

Along with print technology from Europe, there came European commercial products and their advertising images appearing in newspapers and magazines in English as well as local languages. Looking at a few mainstream advertisements published in English press in early 20th century, a distinct feature of representation seems to be the contrast between European and Indian facial features and lifestyles, as if different products were meant for clients of different classes or identities, even if the product was imported from Europe. This is interesting because the two contrasting advertisements were often published in the same English periodicals or printed spaces that were seen or read by Europeans as well as the Indian elite.7 But often, the European dress or mannerism is also presented to the Indian readers (such as in a 1930 Urdu advertisement for a health supplement drug Okasa) as a role model of modernism which the Indians (or Urdu readers) ought to adopt. The style of art or illustration used in much of this print culture is definitely influenced by photography, even though the photographs themselves are not used so liberally due to technical limitations. Much of colour printing in early era was done in Europe since colour presses were not so much in vogue in India until the start of 20th century.

Ismat, the cover of an Urdu magazine for women. Issue of February 1938, published from Delhi by Rashidul Khairi (editor).

Ismat, the cover of an Urdu magazine for women. Issue of February 1938, published from Delhi by Rashidul Khairi (editor).

Many illustrated Urdu newspapers and magazines had started appearing in north India from the middle of 19th century, mostly published from Delhi and Lahore, some of the first being Avadh Akhbar8 and Dehli Urdu Akhbar which was started in 1836 by Maulvi M. Baqar. These were followed by many other periodicals, and soon there appeared some women’s magazines too, catering mostly to the purdah women in ashraf or elite families of north India. Among them, Tahzib un-Niswan was started at Lahore in 1898, whereas Khatun of Aligarh ran from 1904 to 1914. Similarly, Ismat, started by Delhi’s Urdu novelist Rashid-ul Khairi in 1908 ran the longest until 1950s. These magazines raised important social issues, especially the degrading position of Muslim women in society, even though reaffirmed their domestic roles by dealing with topics like sewing, cooking, childrearing, and home economics etc.9 Many of them carried images not only to illustrate the topics but also for decoration. This popular print culture also featured illustrated Urdu books on cookery, embroidery and other similar topics that were quite sought after in the families. The images at this point carried a somewhat European style of human features and backdrops, and there was no hesitation in the depiction of human body, even of women.

Photograph of an unidentified film actress printed along with Urdu poetry. Magazine Alamgir, Lahore, 1935. Photo by S. Shah Ali, Hyderabad.

Photograph of an unidentified film actress printed along with Urdu poetry. Magazine Alamgir, Lahore, 1935. Photo by S. Shah Ali, Hyderabad.

In some of the early Urdu magazines, the printed visuality and ‘beauty’ is not taken purely for its sensuousness. There have been efforts to connect or compliment the images with ideas in written word, especially poetry, which is supposed to take the images to a higher level. Many magazines carried images of natural beauty or pretty women, usually in colour, accompanied by creative captions and often complete poems written to pay tribute to the image. Some magazines, such as Alamgir of Lahore (circa 1920-30s) carried reproductions of oleographs depicting scenic beauty (often painted by the local artists like Hakim Faqir M. Chishti or Prof. Allah Bakhsh), which were ‘commented upon’ in romantic poetry by well known poets.

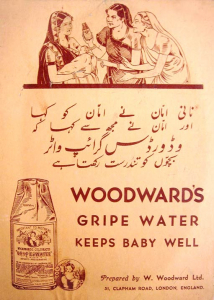

Advertisement for Woodwards gripe water in Urdu, published circa 1930s. The Urdu text says ‘granny told my mother, and mother told me, Woodwards gripe water keeps babies healthy’.

Advertisement for Woodwards gripe water in Urdu, published circa 1930s. The Urdu text says ‘granny told my mother, and mother told me, Woodwards gripe water keeps babies healthy’.

Delhi and Lahore were not only great centres of print production but even had complementary business relations until 1947 with a large postal traffic between them.10 Besides books and magazines, these two centres also produced other popular ephemera such as religious and decorative posters and calendar art that was sought after all over India.11 But the 1947 Partition of India gave a big blow to the print culture as these large business centres were cut off. The family business of Ismat magazine was carried from Delhi to Karachi by Rashid’s son Raziq-ul Khairi, and continued there for long. But the partition also reoriented many businesses on both sides of the border, and after a brief lull, Delhi’s Urdu print culture picked up slowly. There appeared many other popular magazines in Urdu from Delhi around 1950, some of them continuing until the end of the 20th century.

Whether in the magazines meant specifically for women or for general readers, when it came to attracting potential buyers towards a product, the female body has always been used as a staple feature in advertising right from the time commercial advertisements started appearing in India. Urdu magazines and their advertisements were also not devoid of such gender stereotypes. The female body not only solicited the attention of the male viewer, it also assuaged masculine anxiety in reproducing and reaffirming traditional roles for women. This regressive tendency of the media towards women is somewhat paradoxical given the advertising industry’s self projection as the face of “modernity” and “progress”. In Urdu printed literature, most of the images and advertisement messages reflected a romantic notion of the female body, largely promoting cosmetics and beauty products. Moreover, the modern woman also had many more chores to do in her daily life, as the advertisements showed – maintaining new standards of domestic cleanliness, handling the new gadgets of kitchen and laundry, and using newer ways of keeping the husband and children happy.12 In a popular Urdu novel of 19th century, Mirat ul-‘Arus (the Bride’s Mirror) the protagonist Asghari’s house was in such perfect order “as if the house were a machine, with all its works in good order”.13

Advertisement for perfume products from Asghar Ali Mohammed Ali of Lucknow. Published from Lahore in 1931.

Advertisement for perfume products from Asghar Ali Mohammed Ali of Lucknow. Published from Lahore in 1931.

Advertisement for Jharan hair oil, printed in the Urdu magazine Musavvir, Mumbai, 1941.

Advertisement for Jharan hair oil, printed in the Urdu magazine Musavvir, Mumbai, 1941.

Advertisement for Murphy radio featuring Indias beauty queen Miss Naqi Jahan. Printed in the Urdu magazine Sham’a, June 1967, Delhi.

Advertisement for Murphy radio featuring Indias beauty queen Miss Naqi Jahan. Printed in the Urdu magazine Sham’a, June 1967, Delhi.

Roghan-e Tilismi (the magical oil), advertisement for an oil to enhance virility, available on mail-orders. Circa 1930.

Roghan-e Tilismi (the magical oil), advertisement for an oil to enhance virility, available on mail-orders. Circa 1930.

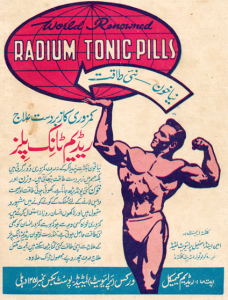

Studying the commodity images and their advertisements in late 19th and early 20th century Indian print is like conducting archaeology of the times. Each product and its promotion tells us so much about the development of society in colonial India, the likes and dislikes of people and even the social hierarchy being addressed in the advertisements. A large number of printed ads are about wonder drugs and magic pills that can treat all your ailments and miraculously bring back your youth. Many of these products are European while some also use traditional Indian medical systems like Ayurveda and Unani. There seems like a mass anxiety about bringing one’s health back using all sorts of oils, lotions, potions and tablets. Through these magazines advertisements, one also realises that an active culture of mail-order purchases were already common then, since most advertisements provide the option of sending the product by post and payments by money-order.

Advertisement for Radium tonic pills, printed in Urdu magazine Bisvin Sadi, June 1976, Delhi.

Advertisement for Radium tonic pills, printed in Urdu magazine Bisvin Sadi, June 1976, Delhi.

The wonder drugs abundantly included potions for enhancing sexual vigour and virility, and treatments for infertility. There are drugs that are ‘guaranteed to make women give birth to a male child only’, stressing on the ‘misfortune of families that have not had a son despite trying hard for many years’. There are of course advertisements for illustrated chapbooks such as kama-shastra and kokh-shastra that explain to the newly wed couples the secrets of a blissful married life in simple Urdu. Then there are naughty and secretive booklets with erotic tales of a beautiful woman’s nuptial night and so on (with titles such as Suhagan ka Suhag). All these books could be ordered by mail and ‘will arrive at your doorstep in an unmarked parcel for secrecy’ said the ad.

Urdu advertisements for clocks and wrist watches from General Trading Agency, Ludhiana, Punjab. Printed circa 1930.

Urdu advertisements for clocks and wrist watches from General Trading Agency, Ludhiana, Punjab. Printed circa 1930.

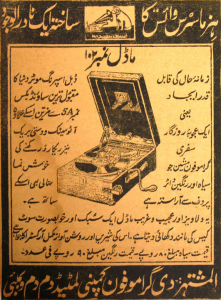

A number of mechanical devices and commodities that had just arrived from Europe became not only a craze but also a symbol of high culture. Radio and gramophone were the most common forms of mediated entertainment, and such gadgets were commonly advertised in Urdu periodicals. Many other innovative imported products were available in the market to inspire awe and wonder from the buyers, such as alarm clocks, portable printing machines, shaving machines, toy pistols, torchlights, movie projectors and even devices that made you invisible! Gramophone records were especially popular among the Urdu readers as a large number of recordings of qawwali, Urdu poetry and Islamic devotional music was made available on from early on, and their advertisements regularly featured the latest released discs.14

An advertisement for His Masters Voice gramophone player published in 1935 in an Urdu newspaper.

An advertisement for His Masters Voice gramophone player published in 1935 in an Urdu newspaper.

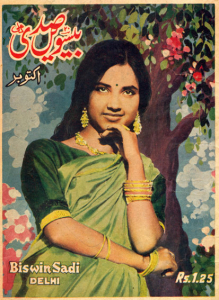

From the pre-1950s era we move on to the second half of 20th century where new magazines and Urdu publishing houses started emerging in print centres like Delhi. Old Delhi or Shahjahan had a large business of hakims or traditional doctors, some of whom hailed from families that served the Mughal rulers. New businesses emerged from such families, with brand names such as Hamdard and Sham’a Laboratories that are active till date. Besides selling their traditional pharmaceutical and health-related products, such companies also helped in establishing a vibrant culture of popular print. Urdu periodicals like Bano, Biswin Sadi and Sham’a emerged as some of the most hot-selling family magazines in north India. Along with them came small-sized ‘digests’ such as Huma, Huda, Shabistan and Mehrab that focused on religious as well as general topics. While Bano and Biswin Sadi catered to women’s issues, Sham’a (along with its Hindi counterpart Sushma) was the most celebrated magazine devoted to Indian cinema. Sham’a has been very liberal in printing glamorous images of film actors and actresses along with the film gossip. Of course, these magazines also printed advertisements of the products from their parent companies.

Cover of the Urdu magazine Bisvin Sadi, printed October 1960, Delhi.

Cover of the Urdu magazine Bisvin Sadi, printed October 1960, Delhi.

Advertisement for United pressure cooker, printed in Urdu magazine Bano, April 1976, Delhi.

Advertisement for United pressure cooker, printed in Urdu magazine Bano, April 1976, Delhi.

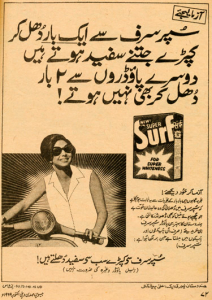

Advertisement for Super Surf. Printed in the Urdu magazine Bisvin Sadi, October 1969, Delhi. Advertisement designed by Lintas.

Advertisement for Super Surf. Printed in the Urdu magazine Bisvin Sadi, October 1969, Delhi. Advertisement designed by Lintas.

The body of a woman continues to remain a prominent feature in much of later 20th century print culture. Images and art styles change but the older domestic roles of women get reinforced with newer products and services. The women in Urdu advertisements not only work in offices and drive scooters but also attend parties with male friends. But they also have to use more advanced types of detergent powders and futuristic pressure cookers at home.

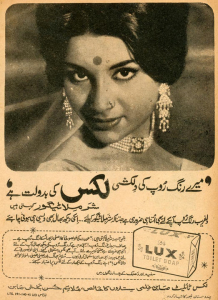

Advertisement for Lux soap featuring Indian film actress Sharmila Tagore. Printed in the Urdu magazine Sham’a, June 1967, Delhi. A byline of the advertising agency Lintas can be seen in Urdu at bottom left.

Advertisement for Lux soap featuring Indian film actress Sharmila Tagore. Printed in the Urdu magazine Sham’a, June 1967, Delhi. A byline of the advertising agency Lintas can be seen in Urdu at bottom left.

Among various commodities of print era, soap has been the most evident symbol of modernity, hygiene and a projected beauty which has been represented in popular print literature through its advertisements, specifically that of one soap brand – Lux.15 It was projected as the soap used by the film stars and there was hardly any famous cinema actress of Indian cinema who did not appear in the Lux soap advertisements. Since popular cinema represented the dreams of millions, the image of luxury soap too allowed them to imagine themselves like the film stars.

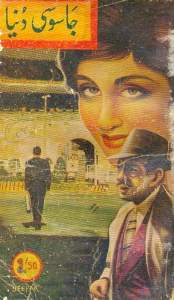

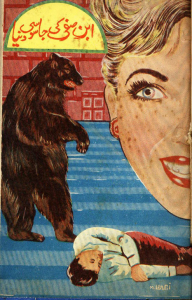

There was no dearth of periodicals devoted to detective stories and novels right from the late 19th century. But from the mid-20th century, Mujrim and Jasoosi Duniya emerged as the most sought after digest-sized volumes with popular detective characters like Imran and others. Jasoosi Duniya’s author Ibne Safi was born in 1928 near Allahabad (Uttar Pradesh) and later moved to Pakistan. These detective novels are characterised by colourful cover art that itself could be documented and studied.16 The covers are usually filled with pictures of pretty women, guns, blood and gore that not only reflect the story but also attract the buyers who would probably purchase them at bookshops on railway platform or the roadside shacks.

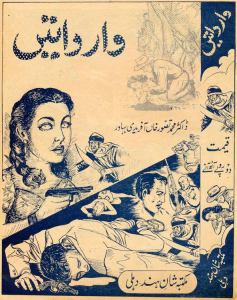

Wardatein (Incidents), the cover of an Urdu detective novel published from Delhi, 1940.

Wardatein (Incidents), the cover of an Urdu detective novel published from Delhi, 1940.

Jasoosi Duniya (Detective World), cover from a series of novels by Ibne Safi, a popular author who started publishing from Allahabad in 1940s.

Jasoosi Duniya (Detective World), cover from a series of novels by Ibne Safi, a popular author who started publishing from Allahabad in 1940s.

Ibne Safi ki Jasoosi Duniya (Ibne Safi’s Detective World), cover of a detective novel. Circa 1960.

Ibne Safi ki Jasoosi Duniya (Ibne Safi’s Detective World), cover of a detective novel. Circa 1960.

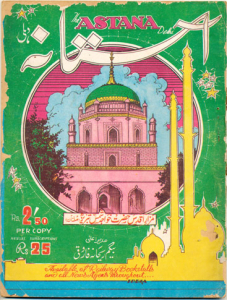

Cover of a religious magazine Astana featuring the Sufi shrine of ‘Hazrat Khwaja Shams Tabrez, Multan,’ published at Delhi, 1970. The saint’s name is Shah Shams Sabzwari (died 1356), not to be confused with Shams Tabrezi, the 11th century poet and spiritual instructor of Mevlana Rumi, who is buried in Khoy, Iran.

Cover of a religious magazine Astana featuring the Sufi shrine of ‘Hazrat Khwaja Shams Tabrez, Multan,’ published at Delhi, 1970. The saint’s name is Shah Shams Sabzwari (died 1356), not to be confused with Shams Tabrezi, the 11th century poet and spiritual instructor of Mevlana Rumi, who is buried in Khoy, Iran.

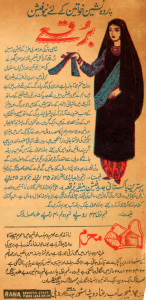

It would be incorrect to assume that 20th century Urdu print culture was only filled with liberal images of women and sensuality. One cannot ignore a large volume of literature devoted to religion and Muslim identity. Delhi’s publishers produced periodicals like monthly Molvi (1950-60s), Aastana (1970-80s), and the digest-sized Huda that focused on devotional literature – inspiring stories from Islam’s history, religious poetry and sermons. There were images too – mostly of the buildings of Mecca and Medina shrines as well as those of Indian Sufi shrines. The magazines also carried art work based on calligraphy of Qur’anic literature in Arabic. But even these magazines until 1980s were liberal enough to carry advertisements of all the regular commodities such as clothes, shoes, clocks and all other worldly objects required in daily life. However, they did carry ads for fashionable burqas (veil) that were meant for modern Muslim women, stressing yet again on ideas of modesty and chastity of women in the Islamic society.

‘New fashion burqe’ for purdah-nashin (veiled) women, an advertisement published in 1950s from Delhi.

‘New fashion burqe’ for purdah-nashin (veiled) women, an advertisement published in 1950s from Delhi.

Looking at these advertisements in Urdu magazines one may wonder as to what is so special about them. After all, most of them are simply Urdu versions of the mainstream product advertisements appearing in English or any other Indian language. Why should one see them segregated from the mainstream print and commercial culture and as something special? Well, probably their being Urdu versions of the regular product ads is really not a big deal. But what is special is that much of the examples presented here are from the early and mid-20th century which one doesn’t see any more in Urdu print culture. They belong to a sort of a golden era of Urdu print culture through which one can learn a lot about the openness and eclectic tendencies of Urdu readers.

It is important to document and study these images because many of those liberated periodicals are no longer printed, and new Urdu magazines are not considered commercially rewarding by the Indian industry and commercial establishments to put their ad in them. Until 1980s, almost all major advertising agencies in India had creative staff or resources in Urdu due to a high demand in the language. A large number of ad campaigns were originally conceived and designed in Urdu rather than simply copied from the English templates. Their artists too often came from a lineage of Indo-Muslim artistic tradition, such as those doing calendar art, which too has almost died. The decline of Urdu print culture may have occurred parallel to a process of ‘ghettoisation’ of the Indian Muslim community in India since 1947.17 These have been complex processes and no single factor can be considered responsible for them. But Urdu language and its print culture is not dead yet. New magazines and popular literature is being published, but the tendency has mostly been to impart values of a rather sanitised religion among the new generation of Muslims. The visual culture of these magazines reflects icons and motifs of the Arab world rather than India, as the new global Muslims increasingly seek their cultural identities in Arabia.