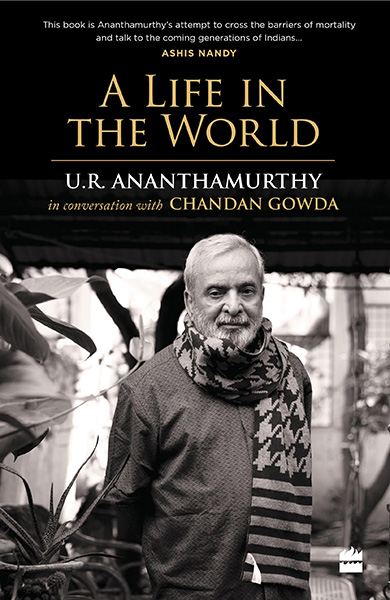

Chandan Gowda is professor of sociology at the Azim Premji University, Bengaluru, and writes a regular column for Deccan Herald. He is also a literary translator, and has translated Kannada fiction and non-fiction into English, including Bara, a novella by U R Ananthamurthy. He is presently editing and co-translating Daredevil Mustafa, a book of short fiction by Purnachandra Tejasvi, and completing a book on the cultural history of development in old Mysore. His most recent book, A Life in the World (Harper India, 2019), is a collection of interviews with U R Ananthamurthy and forms the subject of this conversation with Salim Yusufji.

Salim Yusufji (SY): Let us begin with your many-sided acquaintance with U R Ananthamurthy and his work. Apart from knowing him personally, you’ve played the lead in the TV adaptation of Bharathipura, translated from his work, done these extended interviews with him. Tell us about what Ananthamurthy has meant in your life as a reader, columnist and teacher, especially how you relate to his imperative that writers localise themselves, be rooted in a regional tradition.

Chandan Gowda (CG): URA was a deep influence. I was drawn to how he had sought to work out the very difficult relationship between the traditional and the modern worlds in his writings and activism. I came to know him well after my college years due to my friendship with his son, Sharath. He was very affectionate towards me. My father and he knew each other well. He had been URA’s student in Mysore. There was this old association too.

URA loved conversations. He could talk for hours without letting the intensity diminish. I cherish the time I spent in his scintillating company. His literary seriousness, his ever-wakeful political instincts, his joy in ideas, his interventionist attitude which was rooted in a quiet courage and abjured cynicism or despair, his ceaseless curiosity about everything, his warmth, among other striking qualities, made him unlike anyone else I knew.

The imperative that writers localise themselves, stay rooted in regional tradition is a complex one. Clearly, there is not one local position: the local for instance harboured within it the mainstream and the marginal, the classical (marga) and the folk (desi), both of which contained valuable ways of being and doing, and which wouldn’t have been insular spheres and are likely have related to each other on some plane, even if the history of that relation might have been forgotten. The poles within the local will be in a different relationship with the non-local, be it a dominant one or a non-dominant one. For instance, classical Kannada could be in a relation of subordination to classical Sanskrit and free from that kind of relationship with classical Tamil. Similarly, in the modern world Kannada is in a subordinate relation with English. In other words, the marga and desi are shifting categories and reveal mutual interplay, inter-tensions, through time. So being a locally-grounded writer is also to evolve a writerly self within this complex field of literary aesthetics. It didn’t imply a closing in on oneself. It was a vantage point for keeping oneself open to outside influence. It even lets writers and artists smuggle in newness inside a culture without it taking the form of an alien imposition or an iconoclastic gesture. Being grounded in local tradition/s allowed one to be what URA was fond of characterising as ‘a critical insider’. One wrote as a member of a community. Being an insider required one to be rooted in that community’s literary, political, cultural conversations, its metaphoric imagination. URA though was not absolutist about this view. ‘If you feel like writing in English,’ he said to me once, ‘you must write in it.’ He was also not relativist about literary value. Whatever the variations in historical and literary experiences, there was for him such a thing as great literature1. You won’t find him making concessions on grounds of political correctness.

SY: He speaks of coming round to accepting the literary value of work done by Indians in English, particularly R K Narayan and Raja Rao. Otherwise, in the ten interviews of this volume, URA presents a highly resolved view of the arc of his work. An occasional note of ambivalence does come through — he both prizes and criticises family life in India — but we don’t get a strong sense of shifts and turnarounds in his position, beyond stray regrets about the socialist movement and its lack of sympathy with landowning farmers. Was continuity indeed the dominant note of his thinking and writing life, or was it more of a construction from hindsight?

CG: There were significant shifts on several matters. In an early interview, you might remember, he says he was schooled in Dvaita philosophy as a young boy, but now identified himself as an Advaitin. In the 1970s, Gandhi’s philosophy comes to assume a great importance for him. During the 1990s, his friendship with DR Nagaraj, the literary critic, made him more keenly aware of the extraordinary literary achievements seen in Kannada folk epics. He also came to have renewed regard in his later years for his literary predecessors like Kuvempu, whom he and his fellow-writers of the Navya (modernist) phase had taken to be romantics who were naïve about modernity.

Critics have often commented on the shifts in intellectual concern in his fictional works. The ruthless focus on the life-denying aspects of attachment to community and tradition seen in his first novel, Samskara, made way for a closer examination of the difficulties of initiating social reform in local society from a placeless liberal point of view in his next novel, Bharathipura, and then to the disclosing of the dominance of modern knowledge and its threat to non-modern cosmologies in the short story, ‘Stallion of the Sun’.

SY: My impression is that his test of Kannada was its ability to enable diverse voices.

CG: You are right. Enabling diverse voices was important for him, not because that was good to do for reasons of social inclusion or egalitarian ideology, but because of the belief that they exhibited a capacity for high literary accomplishments. And, making space for dissent didn’t mean an approval of any kind of dissent. He remained unequivocally critical of violence as a means of achieving political ends, whether it was of the right or of the left-wing variety.

SY: Inclusion demands more than tolerance, accommodation or literary approval. They are inadequate in response to radical cultural criticism, can even seem a brush-off. When URA says that the dalit politician, B Basavalingappa, is justified in his dismissal of Kannada literature, his position is reminiscent of the way Gandhi had once said Ambedkar would be justified in hitting ‘us’ (caste Hindus) with shoes2. This kind of remark leaves the critic looking intemperate, while robing the speaker in patience and tolerance. The critic’s charge, a serious one, of inhumanity at the core of tradition, does not impel a rethink on the value of these traditions. Would you agree with this analogy?

CG: URA’s response has to be viewed differently. When B Basavalingappa, the dalit leader and minister for municipal administration in Karnataka, dismissed all of Kannada literature as ‘boosa (cow fodder)’ in 1973, there were loud protests across the state and even violent attacks on dalit students. URA stood by him at that time. Recalling that episode in our conversations, he said: ‘Everyone attacked him. I said, ‘I don’t think that Kannada is cow-fodder, but if I were born a dalit, and if I had to read only sectarian literature in Kannada3, I would have said what Basavalingappa said. So he has every right to say that. It is not against Kannada as such, it is against what it teaches them.’

This response insists that Basavalingappa had a legitimate view and that view needed to be given a hearing, and not summarily dismissed. Basavalingappa’s experience had allowed him an insight that had evaded the upper castes. By saying that he himself didn’t think all of Kannada literature was worthless, URA was keeping himself open to a dialogue with Basavalingappa, a stance that does not take away the dignity or the weight of the latter’s response.

An excerpt from URA’s response to ‘the Boosa Movement’ that appeared in Praja Vani, the leading Kannada daily, in 1974, might be good to revisit here: ‘Is it any surprise if the panchamas view Kannada literature, which is filled with the literature of the very sects and religions that has kept them out from the start, as meaningless? Also, when the panchamas give up the sectarian heritage of Kannada literature, might it not be possible for them to bring in a genuine newness into Kannada, as it happened in the case of Dalit Panthers in Maharashtra?’ (translation mine)4.

SY: There’s an anecdote in the book about the Udupi Pejawar swami, who is accused of purifying himself with cow urine after visiting the homes of dalits. He later reveals — to URA, in confidence — that he had not in fact undergone a ritual cleansing, merely allowed the report to go uncontested. That rather defeats the point of challenging caste, don’t you think?

CG: While recalling that episode from the early 1970s, URA explains that such a gesture from a religious head could ‘convince my mother that untouchability is wrong.’ He adds: ‘She can never be convinced with any of your rational arguments. But when the Swamiji, whom the older people worship everyday at home, does something like that, there is a change of feelings among them.’ He is really pointing to the challenge that lies for modern activists in engaging the socially orthodox minds. I see at least two concerns here. One, the socially orthodox people are attached to a model of social order which is at variance with the one driving the vision of secular egalitarianism. A proper understanding of these attachments becomes necessary for engaging them. Well intentioned secular exhortations in favour of caste equality in themselves might not then be adequate to bring about, to use URA’s phrase, ‘a change of feelings,’ a genuine change of heart. Besides, custodians of religious morality like Pejawar Swami, who are authority figures for the believers, need to be understood and even made room for in the scheme of activist struggle.

Clearly, Pejawar Swami’s visit to dalit homes disturbed his followers who then felt impelled to deny it ever happened. The Swami’s silence in response though shows that he didn’t want to upset the wishes of his followers any more than he already had. He feared that they would reject him. URA also recalls him admitting that he lacked the strength to take them on. The work of ‘challenging caste,’ URA seems to suggest, happens in several ways. Some individuals are more heroic than others, some are more creative than others. And, the radical activist option is unlikely to be available to all. I see URA asking for patience and understanding in how the efforts to challenge caste can only be multiple and incremental. Abjuring external activist standards of what counts as caste reform and what doesn’t, the reform of caste is better viewed as emerging out of a variety of well-intentioned acts, both large and small.

Also Read | Reading and Translating U R Ananthamurthy

SY: A couple of years before A Life in the World, you published a selection of Gauri Lankesh’s writings — including several pieces that appeared in English for the first time[5]. She, like Ananthamurthy, was a cosmopolitan figure committed to writing in Kannada — which she had to learn as an adult. There have been several instances in Karnataka’s cultural life of writers choosing Kannada over English; Girish Karnad is another figure who comes to mind. Each of them had an independent voice and broad sympathies, but do you think their choice bolstered the political hegemony of Kannada? It is the language of an overwhelming majority in the state, but not of every native community. Do you think the role URA played in the renaming of places confined cultural horizons, by strengthening one set of claims to belonging over many others?

CG: All of them were bilingual personalities. They participated in discussions in Kannada as well as in English, were featured in newspapers in both languages. Gauri Lankesh wrote a weekly column for Bangalore Mirror for a couple of years. Their activist interventions, even when expressed in Kannada, therefore cannot be seen as exclusionary affairs. If your work is directed towards Karnataka, Kannada becomes a necessary medium of engagement. Most speakers who see themselves as belonging to other language communities of the state, especially those outside Bengaluru, understand and speak Kannada since they would have learnt it in school. Writers and journalists from Tamil, Telugu, Urdu, and the ‘smaller’ languages lacking a script of their own, like Tulu, Beary, Konkani and Kodava, have registered a distinct presence for their language worlds in the Kannada public all through. I’m yet to hear an accusation that democratic activism in Kannada has posed a linguistic threat to non-Kannada speakers. Besides, thinking and writing in Kannada offer a bulwark of resistance to the hegemony of global activist paradigms that travel so smoothly in English.

In his view, since Bangalore was the capital city of the state, it ought not to alienate the people in the rest of the state. The British had anglicised the local name, Bengaluru, and the new imperatives of state building in independent India behoved the retention of the local name. Other Kannada writers like P Lankesh and Purnachandra Tejasvi also subscribed to this rationale. In A Life in the World, URA clarifies that such a move would help Karnataka evolve in a democratic manner and that he felt confident the renaming wouldn’t imply altered cultural realities on the street in the anglicised cantonment areas. Since the official renaming of the city as Bengaluru wasn’t happening at the instance of a chauvinist political party or activist group, it didn’t portend violence or aggression towards the non-Kannada speakers. He had also told me once that renaming the city as Bengaluru disallowed the corporate imagination of the city as ‘Brand Bangalore,’ from succeeding.

SY: I was thinking of the larger trend of renaming cities in India. Many of them weren’t cities at all in pre-colonial times, becoming urban with a new character, demography, institutions, a transplanted energy, as a national melting pot of sorts. Their deracinated or corrupted names flagged them as neutral ground, with no single founding community. The local names had co-existed with the colonial ones, but with the official renaming these cities sank back into the soil. We have seen a fair bit of bullying of ‘outsiders’: flare-ups between Kannadigas and Tamil speakers, the rough treatment of students from the North-East and from Africa. This was in Bengaluru, but similar altercations have occurred in Mumbai and elsewhere. There’s an electoral calculus that promotes nativist assertion. Do you think URA factored that in adequately?

CG: The activism aimed at securing a symbolic centrality for Kannada in Bengaluru, a phenomenon seen after the city became the capital of Mysore state following India’s independence, has not gained electoral significance. So an electoral calculus cannot have informed URA’s suggestion for renaming the city. He probably saw the renaming of Bangalore in the same spirit as the one that animated the renaming of Trivandrum, Madras and Calcutta as Thiruvanathapuram, Chennai and Kolkata, and not the one behind the renaming of Bombay as Mumbai. At the same time, the anxiety among Kannada speakers about the city being engulfed by ‘North Indians’ — a term that refers to everyone from outside South India and the North-East — has been building up in recent decades, an anxiety that has displaced the older one pertaining to Tamil speakers. These tensions would have evolved even if the city had continued to be called Bangalore in English language media (it has always been Bengaluru in Kannada language media and official correspondence).

It is possible to view the renaming act less as an abridgement of the freedom of non-Kannada speakers and more as a nudge to the latter to engage the local Kannada world in some way, which is a gesture in conformity with the ethics of reciprocity in India’s linguistically organised federal polity. You are right that the cities had a happy bilingual nomenclature in colonial times. But in a federal union, where the three language policy has brought in a model of linguistic fairness and parity which asks people moving from one state to another to learn the language of the host state, the common remark of Kannada activists will seem morally legible and reasonable: ‘We learn Hindi when we go to Delhi, why don’t they learn Kannada when they come here?’

The cultural prejudice against migrants from the North-East and African students, which is not specific to Bengaluru, is indeed worrisome. The overcoming of prejudicial relations with these communities though will need to unfold against local cultural memories and will perforce take locally specific activist routes. In its over five hundred-year-old existence, Bengaluru has held out traditions of civility which allowed for extraordinary linguistic, religious and regional diversity to co-exist. The romantic hero of several commercial blockbusters in Kannada cinema for instance is the son of Nepali parents. Marriages between local men and women with people from the North-East are also taking place. Except in a couple of instances of engineered riots, the tensions between communities have not broken out in violence.

Vested interests have played the Kannada card for extortion and gain in Bengaluru. In a crowded democracy where the paths for the legitimate pursuit of power and resources are restricted to a few, the vested interests would have played another card if the Kannada one wasn’t around. In any case, to the extent the vested invocations of the Kannada card attract tacit popular support, it should be clear that there is a problem. And, this problem cannot be dealt with appeals to generic models of cosmopolitanism, but will have to be worked out through a creative moral engagement with local cultural realities.

SY: Would you say the tide ran out very suddenly on progressive writers in Karnataka, that Ananthamurthy and Karnad’s were lonely voices at the time of their passing? Was Karnataka’s literary culture shoved to a side, in the same project of erasure followed through violently with M M Kalburgi and Gauri Lankesh? How do you view the alteration of cultural life in Karnataka?

CG: URA and Karnad’s espousal of democratic causes found support from among the socially sensitive individuals. In that sense, they were not lonely voices. But it was clear that they were among a shrinking number of Kannada writers holding forth on matters of political significance. A robust tradition where writers participated — and were indeed expected to participate — in political discussions was on the wane. Kannada writers had been a vibrant political presence in the state for decades, with dalit, non-brahmin and women writers raising crucial questions towards expanding democratic activism.

A strong farmers’ and dalit movement in the 1980s also helped create a healthy democratic milieu in the public. Over the last two decades, most writers came to show a decided reluctance to take public positions, especially on the politics of the Hindu right wing. A journalist like Gauri Lankesh, who took over as editor of the influential political and literary weekly, Lankesh Patrike, in 2000, following her father’s death, and human rights activists from non-literary backgrounds, became increasingly vocal in political discussions. Except for occasional interventions, the literary community appears to have abdicated its prior role as conscience keeper of local society. Indeed, political outspokenness is risky today in a way it never was previously. The absence of security alone, though, cannot explain the retreat of writers from participating in political debates. While some of the younger writers do exhibit political courage, the writers for the most part are staying private in the present.

While marking these broad trends, we will also need to note that ‘the public’ itself is a bigger as well as a fragmented entity, with the explosion of television and print media outlets. The middle class has also expanded and its interests tied to the attractions of economic growth, which then realigns its political and social idealism. The near-disappearance of mass-based democratic movements has also not helped vis-à-vis the sustenance of political idealism. The opposition parties in the state are not showing any signs of evolving a vision of democracy that approximates to the altered socio-political realities of the state. On the whole, a grim scenario. I however haven’t stopped hoping for a miracle.