This is the 20th issue of Guftugu, a good time to look back.

In the dark times

Will there also be singing?

Yes, there will also be singing.

About the dark times.

In October 2015, we began the first issue of Guftugu with Brecht’s help. Five years back, we said: Now, as then, Bertolt Brecht reminds us that we can sing in the bad times too; we can sing about the bad times…

We said: Every day we see new evidence of authoritarianism in India — the sort of tyranny that impinges on our cultural work, and on those who wish to partake of what we imagine for them. Even the day-to-day cultural practices by the wide range of people who make up India are vulnerable to the aggression of the “cultural police” in different guises. These policemen want to tell us all what to eat, wear, read, speak, pray, think. They want to tell us how to live.

But we also insisted that: Writers, artists and educators may not be soldiers; but they too have weapons, weapons that are often more effective. We believe this. We believe in the transformative power of the word, the image and the classroom.

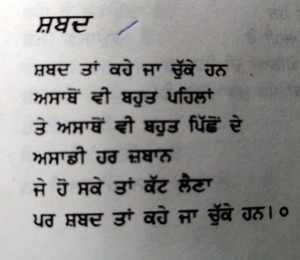

Words

Lal Singh Dil

Words have already been said

much before us and

much after us.

Cut off every tongue of ours

If you can,

But words have already been said.

Translated by Chaman Lal

This belief was confirmed in late 2015. In January 2016, we wrote: The spate of protests by Indian writers in 2015 — against the murder of dissenting writers and thinkers, and the suppression of freedom of expression… (has) once again proved that our land is not yet barren… The writers said many things as they began a chain of protest. This is a tiny sample:

“We cannot remain voiceless.”

“These incidents are an attempt to destroy the diversity of this country and it signals the entry of fascism into India.”

“Silence is an abetment.”

Writers, artists, filmmakers, scientists, scholars… told us about a variety of “official” and “unofficial” efforts to silence dissent and erode constitutional rights. But by speaking up they also told us that the core of our democracy is intact.

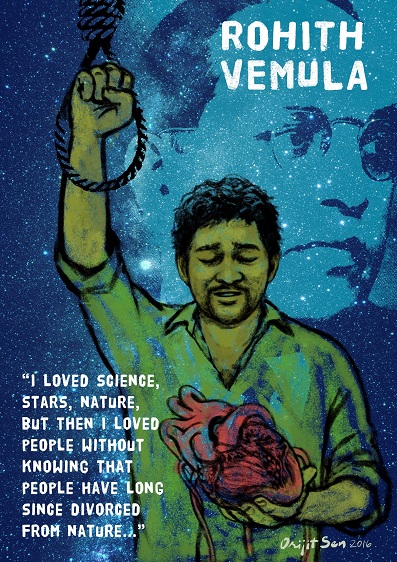

The resistance continued. Our youth took up the gauntlet, as they have before, and as they have again. In May 2016, we wrote of the churning in campuses. We wrote of the horrific tragedy of caste in educational institutions. Rohith Vemula, a research scholar in the University of Hyderabad, committed suicide. In a moving letter he left behind, Rohith said, “My birth is my fatal accident.” It is hard to imagine a more searing indictment of our collective failure — to live up to a Constitution that promises all Indian citizens equal rights.

In July 2016 we wrote about how the voices of the opposition are met: not with arguments, but with threats, abuses, and enquiries based on false charges. We wrote about myth being turned into history and history into myth through senseless rhetoric; films and literature being censored for absurd reasons. We wrote: A new lexicon is underway in which the term “secular” is replaced by “pseudo-secular”; and anyone with a liberal-socialist political persuasion is called a “Nehruvian”, considered an effective put-down. Gandhi can be replaced by Godse as a national icon. Discrimination against dalits is on the increase; farmers continue to be forced into suicide, and workers deprived of the freedom to fight for their rights. But despite this long sampling of an even longer list, the voices of resistance have become stronger. These voices are determined that attempts to drown the cries of the people will not succeed. There’s dismay and courage on display; argument and debate. There’s recognition that India is being unmade. And there is anger at this unmaking of India.

S Vijayaraghavan, ‘Panic Field’, oil on canvas, 7 feet x 3.5 feet, 2006 – 2007

S Vijayaraghavan, ‘Panic Field’, oil on canvas, 7 feet x 3.5 feet, 2006 – 2007

In March 2017, in the midst of witnessing people’s suffering caused by demonetisation, we wrote: … when language is used only to tell lies …that appear in the guise of news and policy and governance, we learn to save our words for the most brutal and shining truth…

When the writer, the poet, the teacher, the lawyer, or the activist are scorned and hounded — or jailed — for their words and their fight for people’s rights, that resolution speaks to us powerfully in 2020.

Then too, our resolution was strengthened when we recalled our legacy in October 2017. We took heart from what our first Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru said in his Inaugural Address at the Fourth P.E.N. All India Writers’ Conference in Baroda in 1957. He said that the writer performs a function that is essential to the country… writers and literary bodies have to be autonomous; the state has no business to interfere in these bodies. Nor, Nehru may have added, if he could have seen where these cultural institutions are today, should they toe the line of the prevailing ideology of the day.

These words apply to more Indians than writers. They apply to all citizens. Nehru’s words from 1957 remind us of who we are, and where we come from.

In November 2018, we asked Is this the India we want? …A country in which citizens are murdered or attacked for being rational, for being critical, for raising voices of dissent, for just being themselves; for being Muslim or Dalit or women. Intimidation, threats. Hatred. Lynching. Sickening violence. Students and teachers compelled to choose between being leashed in thought and word and being hounded as seditious. Institutions built over the years weakened. Economy and development turned into exercises that mock the needs and aspirations of most people in this country. Secularism, scientific temper and rights promised in our Constitution subverted every day. Our democracy, our India, frayed.

We had resounding answers in the form of words and images. The India we want.

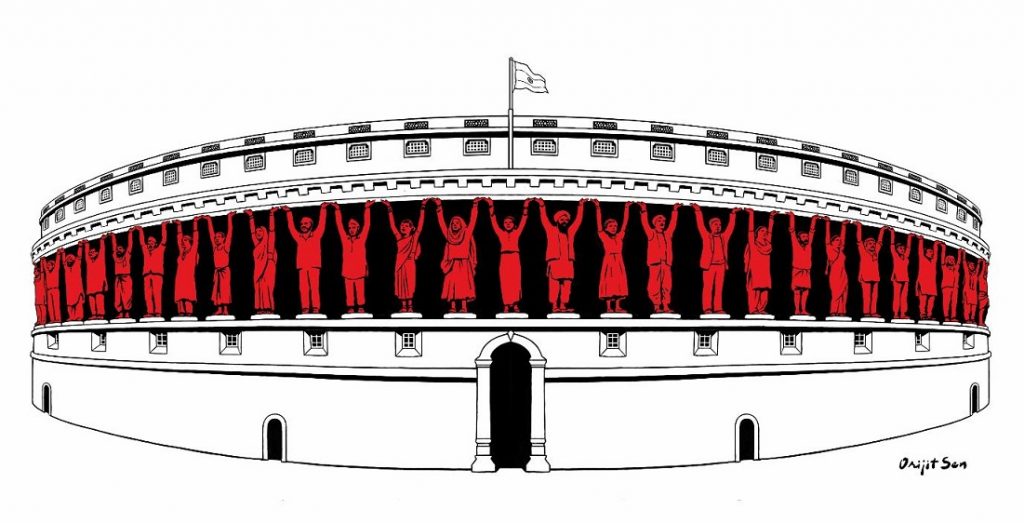

Orijit Sen, ‘Farmers’ Parliament’

In March 2019, we underlined the link between the India we want and reviving our democracy. It is time to restore an India that is infinitely creative in its cultural, linguistic, racial and religious diversity. Despite disappointment of the 2019 general elections, we continued battling for India. In June 2019, we wrote: There are those who battle the idea of India — an idea that insists that the country belongs to all its citizens. And there are those who battle for this inclusive idea of India.

The only constant is resistance, we wrote in September 2019. The insistence on the diversity of cultural practice in India has always been our fundamental premise. What holds the plurality of voices together, what emerges as the central note, is resistance.

‘Blood in every season’, says the poet writing of Kashmir. There’s fire in the chinar tree. The poet can see it.

‘But there’s no sun here. There is no sun here.’

Even as it rains, the poet calls his heart, and our hearts, to be brave:

We will hear words even if the letters do not reach us, even if there is no post office.

We will stand with our sisters and brothers in Kashmir simply because we are human.

We will stand with them like the brave chinar tree, fiery in its suffering.

For years now, 71 years to be precise, the cultural community of India has spoken for equality among all citizens; has fought for freedom of speech; and practised, through language, poetry, song, novel, theatre and film, cultural diversity.

For the last few years, five years, since 2014 to be precise, our voices have had to work harder. We have had to be more insistent about our common legacy.

A gem from this common legacy: On 26 January, 1950, the Indian people — a diverse population that had fought for independence from colonial rule — decided what kind of Republic they wanted to build; what kind of national, collective life they wanted to live. They made promises to themselves through a constitution, and the most fundamental of these promises made up the Preamble: that We the People of India would constitute a sovereign socialist secular democratic republic that would ensure, for all its citizens, JUSTICE, social, economic and political; LIBERTY of thought, expression, belief, faith, and worship; EQUALITY of status and of opportunity; and to promote among them all; and FRATERNITY assuring the dignity of the individual and the unity and integrity of the Nation.

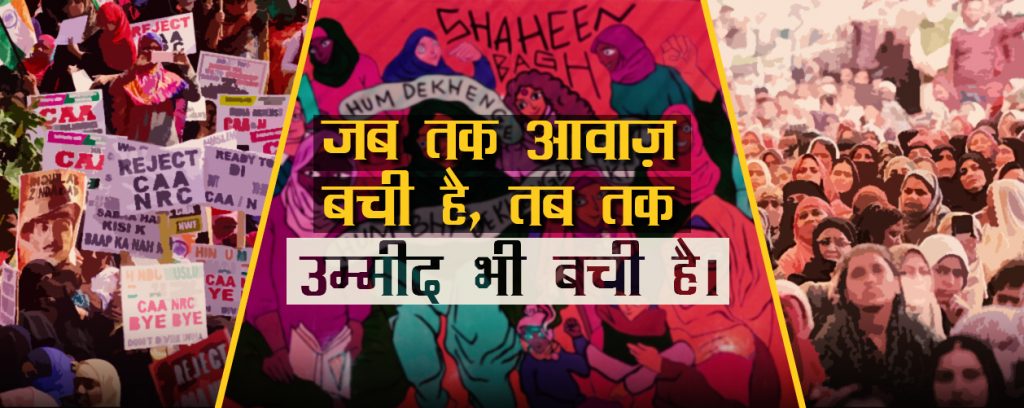

The Preamble makes no compromises with the principles India lives by, and no Indian should. If there is a political party, or a government, or an ideology that makes a mockery of these principles, we have to resist. And this is what our brothers and sisters across the nation have done, every day. This is what they — we the people — continue to do.

Image courtesy Indian Cultural Forum

Image courtesy Indian Cultural Forum

And close to the present time, earlier in 2020 with the first of the lockdowns, we declared: The voice is not locked down. We had not forgotten – we have still not forgotten – how 2020 began: the voices of resistance soaring, blending into one voice, a people’s voice, saying No to CAA. No to NRC. No to NPR. No to inequality, injustice, to the brazen distortion of the Constitution. The betrayal of every person’s rights. Women, children, men, old, young – everyone marched, occupied streets, spoke, wrote, sang. Then came a more literal virus that would show up more than one disease among us. Diseases that have been around for long, and that grow – every time a migrant worker dies walking home; every time a dissenting voice is hounded or arrested; or every time there’s proof that hunger is the worst virus of all. In such times, can we fall silent? No. Guftugu presents, in collaboration with many friends, artists and poets, images and words through which our artists, our poets, tell us powerfully, beautifully: The voice is not locked down.

We began the Guftugu project with this conviction: The cultural fraternity speaks in two places and in two different ways: in public space, to and along with their fellow citizens; and through their critique of our society, a critique embedded in the nuances, layers and texture of their work. Over 20 issues of Guftugu, we have presented ample evidence of this.

And here we are, faced with more than one virus. Here we are, our voices intact. This is the twentieth issue of Guftugu. It’s a good time to look ahead. To raise our voices, to speak with full-throated strength.

Image courtesy Indian Cultural Forum

Image courtesy Indian Cultural Forum

K Satchidanandan

Githa Hariharan

August 2020