Pherans and Arched Doorways

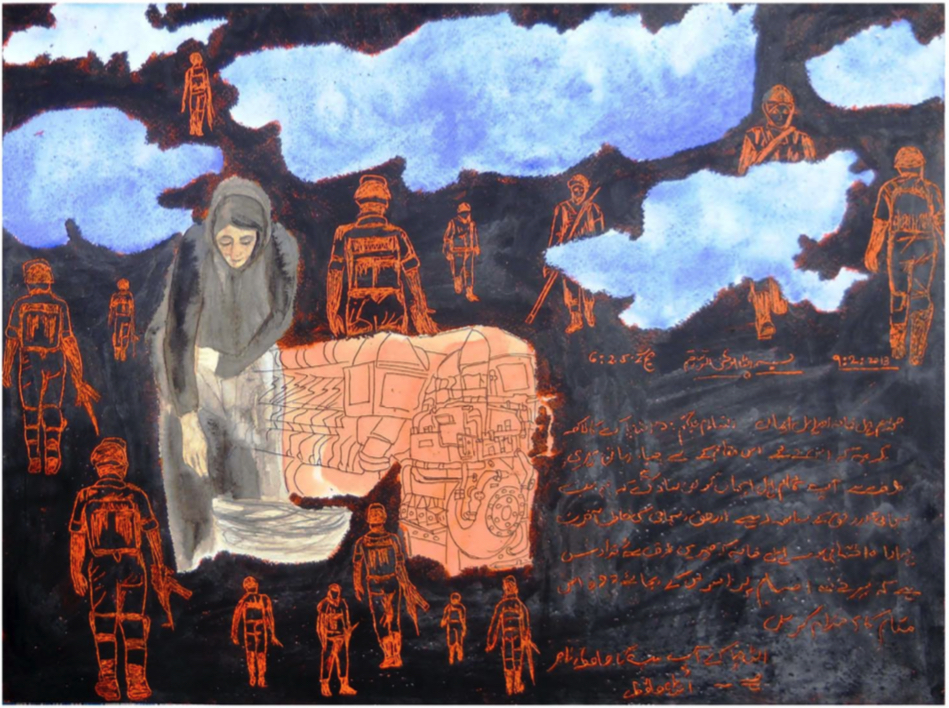

Parvez sat quietly, listening to Falaq talk about her mother being killed by a stray bullet when she was eleven. She narrated her memory of it gently, without a trace of anger or blame. Her mother had gone to buy milk that evening. The next thing the family heard was the sound of gunshots and everything went silent after a little while. When she didn’t return even after the usual interval of time between gunfire sounds and the resumption of the kind of normalcy people were used to, they went looking for her and found her slumped near the gate of a neighbor. Parvez noticed Falak’s chin tremble ever so slightly when she recalled that while growing up, the shapes of doorway arches always reminded her of the warmth of her mother’s sturdy woolen pherans. As a little girl, Falaq loved to hide in and run in and out of her mother’s pheran. She remembered it as a safe place; a place to run to hide, peer out of and watch, stay warm. She obsesses over Islamic doorways in her art course because it reminded her of pherans, she confessed, smiling weakly. Falaq is a wonderful speaker, Parvez thought. Her voice is even, poised, and confident. She rarely falters while speaking English and tilts her head attentively when listening to others. He sees that those who are listening to her are deeply moved. Parvez wished he could talk like Falaq, be like Falaq, she who could invite you into her vulnerability without seeking to be comforted. Even those who were listening could sense that about her. There was an invisible arched doorway behind which she stayed, politely, stoically, telling her story.

A Bloodied Satchel

Parvez cleared his throat and began to speak in accented English. “I want to talk about a school bag,” he began. “It belonged to my uncle.”

His uncle, Javed, had been thirteen then. On his way back from school, one spring evening, Javed and two of his friends had decided to take Mehnaz poph’s shikara and row it across the Dal lake. She wouldn’t mind. Mehnaz was very fond of her nephew, Javed. He was her brother’s son. Her husband, whose shikara it was, had disappeared five years ago and she spent four years variously looking for him at police stations and army detention centres. She tried to trace him through other networks too, but if he was part of them she was sure he would have sent word somehow. She always went to all the APDP events and meetings. Mehnaz believed that one day her husband would return and they would start a family together. In the meantime, she waited for his return and sold dry fruits and handicrafts to tourists. Mehnaz always had a supply of walnuts or dried apricots in her pheran pockets and fished out fistfuls for Javed, tweaking his nose fondly.

It was a quiet evening and there was nobody outside. Javed and his friends had barely rowed a few hundred meters when the sound of gunfire startled them. It took them a few seconds to realise that they were the targets. “Jump! Jump!”, yelled his friends ducking and diving. Javed sat clutching his new satchel to his chest when the bullets found him. A bloody rose bloomed on the dull canvas satchel. Both his friends had jumped into the lake and the zinging bullets grazed the water before they sank tiredly. Javed slumped sideways on the bobbing shikara, bloody petals enveloping the satchel.

Parvez was thirteen when he discovered the satchel in his grandmother’s room. It was wrapped in a plastic bag. He did not remember what he was looking for when he found it. He asked his grandmother about it. She looked at him for a long moment, seeing and yet not seeing him. It was as if she was seeing other images and his face was merely a screen. Slowly, she pulled him close and sighed deeply. She told him that the satchel belonged to his uncle. Until then, Parvez did not know much about his uncle Javed who had died young.

All that Parvez knew was that Javed had died young from gunshot wounds. Holding Parvez close, running her fingers through his hair, she reminisced about Javed; about how mischievous he was but also very kind; about how she wished he had not gone rowing that fateful evening. What struck Parvez was her resignation as she spoke of her son. There were no tears, no rage, not even sorrow. Parvez’s grandmother died when he was eighteen. When they were sorting through her things, Parvez asked to keep Javed’s satchel. His mother shot him a curious look and nodded. She didn’t ask him why. Some questions were best left unasked.

In September, the rains came. The rivers and streets flooded and water entered their homes. They had to leave everything and flee. Parvez, along with his friends, stood shoulder to shoulder with the army and the NDRF personnel in their rescue operation as they waited for the waters to recede in the neighborhood of their own homes. At the first opportunity, Parvez went back and found the house completely trashed by the waters. He had no hope of finding the satchel but miraculously the plastic wrap had kept it afloat and he saw it lying on top of the stove in the kitchen. Grabbing it, he left the place that was once home. It would take a long time to forget the fury of the waters and even longer to fathom the destruction of what was once home.

Cassette Tape

Parvez turned to Altaf. Parvez remembers that on their first meeting, he thought that Altaf had the blankest pair of eyes he had ever seen. It was as if the artist who painted him had forgotten to add the little white dot of paint at the outer edge of his pupil to animate him. It seemed that all light was absorbed into the dark void of his eyes. Because of this peculiarity, no one knew what went on in Altaf’s mind.

Parvez, like most young men his age, had seen eyes that had been bullied and tortured into shifty submission. They belonged mostly to the generation of his parents and grandparents. Their eyes struggled to meet and hold an outsider’s gaze for more than a few seconds. His own generation’s eyes were filled with a silent seething rage that was carefully masked. They did not look but they did not look away either. But Altaf’s were different. You couldn’t look into his eyes. They did not reflect you back either.

Parvez watched Altaf begin falteringly.He made a wry joke about Voldemort, “he who must not be named”. The smile didn’t quite reach his eyes, nothing did. Those who were listening smiled cautiously, unsure. “In my house too, there was one name no one was ever allowed to mention.” He told his story in a flat monotone.

Altaf had wanted to borrow the cassette tape for a memory art project in art school. He had heard that his grandmother guarded it with a ferocity of a tigress guarding her cubs. Altaf sidled up to her after dinner as she sat staring into space. “Nainn…”, he began, waiting for her to acknowledge his presence. She patted the bed next to her and he sat down. Nervously he asked for the cassette. Altaf realised that everyone around him had gone silent and waited anxiously to see how his grandmother would react. After what seemed like a long moment, she took a deep ragged breath.

“No!”, she said, her voice steely and cold. “Don’t ever mention it. Ever again!”

Altaf had never seen this side of his grandmother. The familiar noises of the post dinner conversations around him resumed; they sounded forced and awkward.

Two days later, as he stood vacantly staring into the distance, his mother came up to him. The tape was delivered to his grandmother a day after her youngest son disappeared, she told Altaf. Initially everyone thought that he had been picked up by the forces. It had happened a few times before. But the cassette tape was delivered even before anyone went looking for him. Apprehensively, the family gathered around the old tape recorder to listen. Their youngest was a beautiful young boy, long limbed, and delicately built. His voice on the tape told them about how he had been picked up more than once and had unspeakable things done to him; of how he could never bring himself to talk about it; of the pain and the guilt and the helplessness. He wondered if his family knew, if his mother suspected it. He knew that as long as he lived, the horror of it would haunt him. To stay alive, he needed a reason to live. Joining the armed resistance was that reason for him; perhaps he could stop it from happening to another young man or woman. The family sat silently, listening to the tape. As the tape ended and turned silently on the spool, Altaf’s grandmother’s body had become taut; slowly and visibly, the light went out from her eyes. It was like watching a candle being snuffed out. Ejecting the cassette with determined fingers, she said flatly, “No one will ever talk about him again.” A few days later, the family noticed a bulge close to her ribs. It took them some time to recognise the angular corners of the cassette under her clothes. Since that day, 27 years ago, she has kept that cassette tape taped to her chest every single day of her life, never uttered his name, or shed a tear. No one understood if this was a coping mechanism, a mourning ritual, or a way of keeping him protected and safe close to her. Altaf turned his blank eyes to his mother and nodded.

Parvez closed the album gently: so many pictures, and equally, so many blank spaces; memories, disappearances, and erasures.