How can one draw grief? How does one draw out grief? People say that grief carries along with it, as close as its shadow, the possibility that it can be left behind or abandoned to float away, released into water as ash. When loss or death no longer feels so familiar that it thickens every moment, thins every pore, one feels as though the anguish of grieving has muted into a tide that washes over one but also abates. This is the grief proper to a loss that has a recognizable place in lifetimes, a place that must be visited or else a life is not really complete. Then there is another kind of suffering over loss, for which the word grief seems almost too slender. This is a sort of suffering forced through something so unbearably dense that what is left of a person is scattered in pieces that never come together again. The task of representing this feeling is almost insurmountable, beyond comprehension, it always falls short. This feeling, if one can call it a feeling, has no resolution.

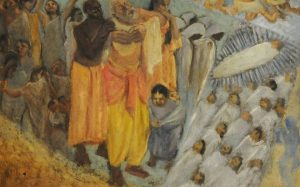

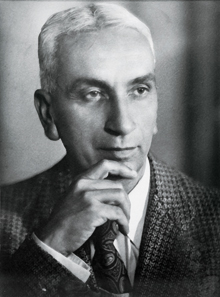

This unreconciled suffering is what S.L. Parasher has portrayed with such brutal and eloquent tenderness in his refugee camp drawings and sculptures. Parasher sketched the figures that inhabit his camp drawings while he was the commandant of a large refugee camp near the railway station in Ambala right after 1947. Sculpted in the aftermath of the obscene violence of the partition riots and the vast influx of refugees that flooded over the border of India and Pakistan, his drawings and terracotta pieces wrest the immediacy of moments. Each piece catches/grasps figures, faces, bodies, clusters of sitting women, rendering through their stillness, unspeakable anguish. There is something both quick and slow in the pieces; the materials were those at hand, paper, lead/pencil, earth: lines rendered in rapid strokes on large sheets of blank paper carried in a bag, pencils pulled out to draw as Parasher walked the lines of refugee tents and settled into a quiet discernment, mud culled from the ground, Ambala earth that clung to form. As Parasher captured the slow dread of his subjects in the act of sitting, of looking out sightlessly, bodies rounded, faces taut, hands falling by the wayside of bodies, hands holding open an odhni, arms nestling heads too heavy to bear their own weight, hands clinging to each other in loose despair, what comes through clearly is his extraordinary compassion, the completeness of his remarkable visionary seeing.

Viewed from across a room Parasher’s work summons people to come and share in the hopelessness that brings the figures into life. One series of drawings is of women, hunched into roundedness; each portrait takes almost the entire sheet of paper; the globular fullness of their bodies so weighed down with bleak despondency that offering a hand to them to hold for a moment becomes an invasion that would seize from them the despair that stitches their lives together. One of the most poignant of these portrayals is a side view of a single woman. Penciled in slightly off center on a white page, she is an almost perfect oval; just a foot stretches out from under her pyjamas to break the surface of her shape. We see one hand, its fingers closed in and hidden, its wrist dropping down onto an elbow, her face huddled in the circle of her arms. Her back is a perfect arc, her legs are drawn up, pyjamas gathered at the cusp of her hips, her chunni falls slowly, gliding down her side. Against alt this roundness is the taut stretch of her the blouse outlining the top of a breast where it meets her arms.

All the tension in the portrayal lies here and is mirrored in the dropped wrist. The contrast offered by their tightness accentuates the vulnerable flow of body, bringing all of the hollow fullness of grief held in the figure to the surface. Without what the lines engender or give her body, she might have just been sleeping in a curl, floating in air or water, at peace.Another figure, whose face is exposed to light and air, sits in a grouping. She is shown in three quarter view; the oval of her body open slightly, revealing her covered face and head, which balance on the worn roundness of legs pulled up against her torso. Her body is hunkered down in a wrapping that shelters it from the deep coldness which appears to inhabit her. Her lower legs shrouded in a salwar, escape from the angled curve of blanket or shawl, feet settled against the ground. Her back is stooped, her hands lost, and her shoulders droop slightly as though she had given up, as if she could no longer hold herself upright as she once did. Hair falls forward unheeded along one side Of her face bared to view, her mouth is tucked away and the white between the edges of her eyebrow and eye slanting sideways is shadowed with the lustre of pain. Something in her seems to remember how she once stood proudly but now that is almost gone, everything that measures an ordinary life fallen by the wayside, only the ruins of that memory haunt the lines of her face and clothing.

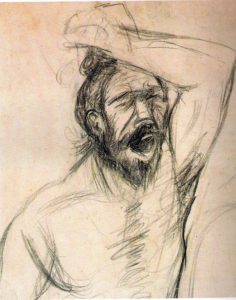

In another, titled ‘Cry’, a man’s grief, so acute that its voice can never stop, whether shattered open or closed out, calls from a mouth pulled through its contours. His forehead is pushed back from the force of the arm that strikes across it, hitting, holding, bracing or resting it is impossible to say; the hand drawn so roughly it releases a blur of movement. Heavy lines, some smudged wide, some falling thickly upon one another, etch eyebrows flat, press eyes flat from weeping, the swelling underneath palpable. Lines radiate down cheeks. The arch of hair pulled upwards into a knot reflgures the tense steep curve of underarm and muscled chest; the force of the sinewed shoulder flesh tugs (vyabhichara) against the hugeness of this grieving, sends the grief so deeply home no other place remains for it.

The portraits bear witness in the lines, in the ways in which they take up space on the page or recede into gray. Lines are dense in some places, layered to adjudicate the shape of a body, lingering sometimes into a single thread. In try a simple pencil stroke from elbow along an upper arm pulls/pushes the darkness laid more thickly on a face towards the light of the blank page. The efficacy of that contrast coagulates anguish through, into and around the person; there is no escape.

What does it mean to witness? The portraits bear allegiance to many forms of witnessing. On one hand they gesture towards forms of representation that have become endemic, mimetic portrayals of suffering bodied in single instances that call into being what has been wrought on entire groups of people. The universal in the singular. The universal secured through the historical. Parasher’s lines seem guileless, the sketches hasty, quick, powerful, the rapidity of the strokes on the page attesting to having been drawn while Parasher was there, present at the very moment, living in the very place to which he could bear witness. Simulating the roughness of cinema verity, Parasher’s style is a record of realism’s iconography. It produces the illusion of a reality effect, of verisimilitude. All of these, though, are merely the semantics on which Parasher relies; they are the familiars of his contemporaneity as well as the archaeology of his own habit of outlining a face; a hand, a moving body, a tum of phrase, a stray philosophical rumination on scraps, on envelopes, on found material.

The efficacy of his work, however, lies somewhere else, both literally and figuratively. What Parasher shows through his seeing, his drstii, is another vision, an anokhaa darshan, his vision goes to the heart of the impenetrable shades that wrap themselves into every figure which he offers a viewer of this series.

How can you even begin to see the stories of dead habitation, marana nivaasa, pravaasa or avastha, arms and legs torn away, flesh dismembered, children so empty; the artifact of statistical description fails in the face of what is ensconced in these figures humanness for whom humanity has no place, for whom insaniyat has gone missing, compounded by betrayal. Parasher’s visual compassionate viewers to each scene, to each manzir, so that one must wear the flesh that has been stripped bare from the figures in the portrayals.

This is the purest relationship between politics and aesthetics: it gifts something of the marriage between witness and representation through drawings where one feels the immediacy of a moment treated as though it were not deliberately crafted to produce that effect. For Parasher the sharing of anguish is more than just a portrayal. Instead it situates the person drawn in the ambit of the person gazing so that an observer can no longer hold onto a god’s eye view, can no longer accede to the pretense that she is outside the frame; perspectival distance is denuded of all its worth.

This is the aesthetic mode through which rasa and bhaava, rasa dhvani theory infiltrates contemporary mores of art practice, and this is perhaps what Theodor Adorno tries to speak of when, in grappling with “incomprehensible horror,” he brings the universal together with the particular, weds the sublime to the social in Aesthetic Theory. Perhaps because he was not schooled formally in the conventions of the art of his day, perhaps because he was trying, as his writing attests, to reach for art making that did not shrink back into seductions mired in formal interrogations, whatever the reasons one finds to justify Parasher’s turns, there is no question that his art is imbued with rasa. When I say this I am not just alluding to the formal conventions, the notes or svara, although it is precisely these conventions that give a raaga the resonances that make it so right for a season, a slice of a day, a space, a series of layered emotions, loss as vipralambha. What I am alluding to is the astounding subtle depths of feeling that Parasher’s work reaches towards in such a way that those very feelings grab hold of viewers and then transform them so that anyone standing before his work is absorbed into the people, animals, trees and houses, light, shapes and movement that bring the work to life. Parasher’s work is living breathing form, and it is this form which takes one to a place beyond the form, not outside the form but through the form to somewhere so uncanny, so pure and so completely overwhelming that when someone looking gives themselves over to it they are no longer themselves. The clock comes to a slow stop, the increments of time through which we have learned to parse the ordinariness of our day slips away almost without notice and in sharing the time of a drawing, a painting or sculpture, we are led simultaneously to another time and to a full emptiness of time beyond even that sense of the specificity of the historical moment which might have inspired a line or a phrase of colour.

Each viewer, as a witness, has laid out before them a visual vocabulary through which they can taste, through the concise economy of line the savage quietude of the rasa of grief, a sthayiibhaava beyond resolution. The lines are vibhaava, in the sequences of their slightness, slack or terse, through the wilderness of their profusion, compact or stringent; they invite anyone who wishes their visitations. A rasika willing themselves to see through them marshals the alphabet of anubhaava, and bodies are scrubbed naked so that they can be filled again through ‘consuming labor of contemplation’. This practice carries Parasher through the later drawings and water colors from Simla, where figures drawn in similar ways exude such ordinary joy, such a quotidian repose as they break for a short conversation, pause during a day’s tasks that their distance from the scenes of 1947 is remarkable. The people from Simla, the single corkscrew trees scripted across long paper, the zigzag of houses condensed along a hill, engender entirely different feelings.

It is the language of bhaava and rasa, splayed across a page, colouring in the hues of feeling without sentimentality and without nostalgia that detaches Parasher’s pictorial sensibility from that of someone who is a recorder of a type of person, from someone whose allegiance to genres of anthropological drawing is completely cogent. The concise acuteness of Parasher’s language renders each object, each person and each thing and carries them to the places to which they properly belong. Parasher’s language becomes his custom, and in later paintings, the mathematics of rhythm disinterred from the conventions of realism reaches towards rasa and bhaava in their purest form.

In an earlier piece which I had written on Parasher’s painting, I had gestured towards Walter Benjamin and the vexed questions critics have about his work, questions endemic to a time when something beyond the quotidian encounters the parsimoniousness of modernity: What is the play of mysticism in a world where histories lie in shards? How does one read the apocryphal metaphors Benjamin offers in ‘Theses in History?’. The usual resolutions for south Asian art critics seem to remain entangled within the tight-listed/pinched/parched binaries of modernity and indignity. For me the answers lie with the voluptuous plenitude of Parasher’s clear-sighted explorations. They begin in the grief beyond redemption of the refugee camp drawings and sculpture from Ambala and close with the magical, uncanny music of the mandala paintings from Delhi.

This essay was first published on The Beacon.