‘Blood in every season’, says the poet writing of Kashmir. There’s fire in the chinar tree. The poet can see it.

‘But there’s no sun here. There is no sun here.’

Even as it rains, the poet calls his heart, and our hearts, to be brave:

We will hear words even if the letters do not reach us, even if there is no post office.

We will stand with our sisters and brothers in Kashmir simply because we are human.

We will stand with them like the brave chinar tree, fiery in its suffering.

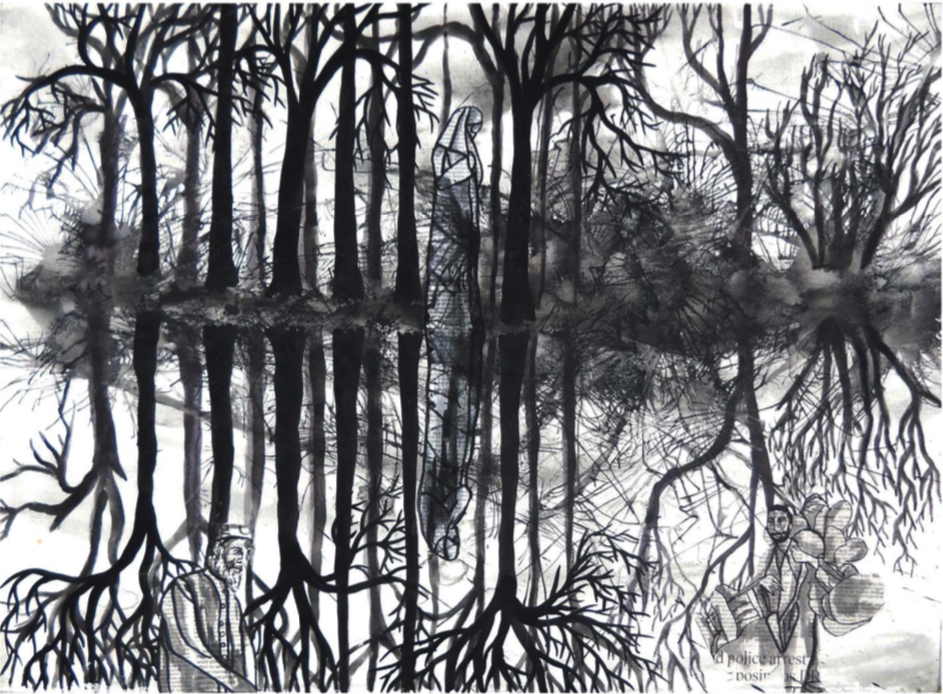

Rollie Mukherjee, ‘Drifting’, mixed media on paper, 43 x 29.5”, 2015

Rollie Mukherjee, ‘Drifting’, mixed media on paper, 43 x 29.5”, 2015

The Country Without a Post Office

Agha Shahid Ali

1

Again I’ve returned to this country

where a minaret has been entombed.

Someone soaks the wicks of clay lamps

in mustard oil, each night climbs its steps

to read messages scratched on planets.

His fingerprints cancel bank stamps

in that archive for letters with doomed

addresses, each house buried or empty.

Empty? Because so many fled, ran away,

and became refugees there, in the plains,

where they must now will a final dewfall

to turn the mountains to glass. They’ll see

us through them—see us frantically bury

houses to save them from fire that, like a wall

caves in. The soldiers light it, hone the flames,

burn our world to sudden papier-mâché

inlaid with gold, then ash. When the muezzin

died, the city was robbed of every Call.

The houses were swept about like leaves

for burning. Now every night we bury

our houses—theirs, the ones left empty.

We are faithful. On their doors we hang wreaths.

More faithful each night fire again is a wall

and we look for the dark as it caves in.

2

“We’re inside the fire, looking for the dark,”

one card lying on the street says, “I want

to be he who pours blood. To soak your hands.

Or I’ll leave mine in the cold till the rain

is ink, and my fingers, at the edge of pain,

are seals all night to cancel the stamps.”

The mad guide! The lost speak like this. They haunt

a country when it is ash. Phantom heart,

pray he’s alive. I have returned in rain

to find him, to learn why he never wrote.

I’ve brought cash, a currency of paisleys

to buy the new stamps, rare already, blank,

no nation named on them. Without a lamp

I look for him in houses buried, empty—

He may be alive, opening doors of smoke,

breathing in the dark his ash-refrain:

“Everything is finished, nothing remains.”

I must force silence to be a mirror

to see his voice again for directions.

Fire runs in waves. Should I cross that river?

Each post office is boarded up. Who will deliver

parchment cut in paisleys, my news to prisons?

Only silence can now trace my letters

to him. Or in a dead office the dark panes.

3

“The entire map of the lost will be candled.

I’m keeper of the minaret since the muezzin died.

Come soon, I’m alive. There’s almost a paisley

against the light, sometimes white, then black.

The glutinous wash is wet on its back

as it blossoms into autumn’s final country—

Buy it, I issue it only once, at night.

Come before I’m killed, my voice canceled.”

In this dark rain, be faithful, Phantom heart,

this is your pain. Feel it. You must feel it.

“Nothing will remain, everything’s finished,”

I see his voice again: “This is a shrine

of words. You’ll find your letters to me. And mine

to you. Come soon and tear open these vanished

envelopes.” And reach the minaret:

I’m inside the fire. I have found the dark.

This is your pain. You must feel it. Feel it,

Heart, be faithful to his mad refrain—

For he soaked the wicks of clay lamps,

lit them each night as he climbed these steps

to read messages scratched on planets.

His hands were seals to cancel the stamps.

This is an archive. I’ve found the remains

of his voice, that map of longings with no limit.

4

I read them, letters of lovers, the mad ones,

and mine to him from whom no answers came.

I light lamps, send my answers, Calls to Prayer

to deaf worlds across continents. And my lament

is cries countless, cries like dead letters sent

to this world whose end was near, always near.

My words go out in huge packages of rain,

go there, to addresses, across the oceans.

It’s raining as I write this. I have no prayer.

It’s just a shout, held in, It’s Us! It’s Us!

whose letters are cries that break like bodies

in prisons. Now each night in the minaret

I guide myself up the steps. Mad silhouette,

I throw paisleys to clouds. The lost are like this:

They bribe the air for dawn, this their dark purpose.

But there’s no sun here. There is no sun here.

Then be pitiless you whom I could not save—

Send your cries to me, if only in this way:

I’ve found a prisoner’s letters to a lover—

One begins: ‘These words may never reach you.’

Another ends: ‘The skin dissolves in dew

without your touch.’ And I want to answer:

I want to live forever. What else can I say?

It rains as I write this. Mad heart, be brave.

Rollie Mukherjee, ‘Inscribed’, mixed media on paper, 28.5 x 21”, 2013

Rollie Mukherjee, ‘Inscribed’, mixed media on paper, 28.5 x 21”, 2013

The Tale of a Chinar Tree

K. Satchidanandan

Jis khak ke sammeer mein hai

Aatish-e-chinar

Mumkin naheen ki sard ho

Voh khak-e- arjumand

-Muhammad Iqbal

( In the conscience of which particle of dust there is the fire of Chinar, that heavenly dust can never feel cold. )

I was born in this dust

with fire that can never cool.

A holy man’s hands planted me here

six hundred years ago.

I blossomed even in droughts

provided shade to people in summer

and warmth in winter

herb for hurts,

a place for children’s play,

a rendezvous for lovers.

My core has memories

just as my hollows shelter birds.

I learnt my many postures from Patanjali,

Panini taught my branches

wind’s grammar.

The semiotics of my stem

comes from Abhinavagupta.

The murmur of my leaves

echo Sharangadev’s hindol.

My roots are hairs standing on end

listening to the verses of

Lal Ded, Habba Khatoon and Arnimal,

my whirlwinds turned

the freedom-songs of Rahman Rahi

into flames kissing the sky.

Shaivites and Sufis alike

meditated under my green umbrella.

I talk ceaselessly to

the dead and the living.

Talking, I change colour:

yellow, mauve, red.

There are only Kashmiris here,

those who hug one another

during Id and Baishakhi,

breaking every stone-wall and thorny hedge,

those who grow lotuses

in their hearts for the birthdays

of Patmasambhav and Guru Nanak

and paint the lake with shikaras,

those who eat from the same plate,

drink the same water and

speak the same language of kindness.

Their religion was liberty

and their flag, love.

They studied their alphabets like this:

Anantnag Arnia

Badgam Baramulla Bishna

Chenani Devsar Gunderbar Hiranagar

Kishtwar Kulgam Kupwara

Kathvua Kargil

Lakhanpur Leh Manda

Pahalgam Pulwama Poonch

Shopian Sopore Srinagar

Talpara Uri Udhampur

Yarippora Vijaypur…

But now only blood spots remain,

the blood of a land being

mutilated and partitioned,

the red blood of fleeing youth

entangled in thorns,

the brown blood of the nail-marks

of the disgraced bodies of women,

the purple blood flowing

from tender hearts torn by bullets:

That is what reddens my leaves now.

The spreading endless variations of red

from the eyes of children, once bluish,

now pierced by pellets:

Blood,

in every season.

Translated by the poet. Read the original here.

September 2019