I shall be taking up two intertwined themes: one is the recognition of what we have begun to call the Other, with a capital ‘O’. The second is the interface of this Other with established society and religion, which I shall be calling the Self, with a capital ‘S’. The interface naturally covers an unending range of activities. I shall take up only a few examples, focusing on connections between religion and society, and the diverse relationships between the Self and the Other.

What we refer to as the Other needs explaining. Put simply it is a person or a group of people who declare themselves to be, or are recognised, as different. The Other or Others differ from the Self — whoever the Self or Selves may be — and the degree of dissimilarity varies. It can be just a passing recognition of difference or it can be expressed in acceptance or rejection.

But however different, the Other demands recognition in every society. This also helps to define the identity of what is called the Self. And like the Self, the Other too has multiple aspects. So in a contradictory way the Other can become, to some degree, a part of the Self. Those whom we see as essentially different, often help us to define ourselves, both individually and socially.

Identifying people by Otherness — or alterity, as it has also been called — can be used to marginalise a section of society, to ghettoise it or even to exile it. Multiple groups all over the world are turned into refugees with the denial of citizenship or by their banishment. This is an old historical habit. Alternatively the Other can be incorporated into one’s society as was also done repeatedly in the past to create what we call civilisations. These have been projected as unitary and monolithic but in fact they were porous, and were textured from multiple divergent strands.

The relationship of the Self with the Other can change over time and move from being distanced to being proximate, or the reverse. The identity of each can also change but the presence of each is an important component of social relations. Every society marks the Self from the Other in diverse ways.

The recognition of Otherness was worked into a theory in the last two centuries. Colonial thinking had sharpened the definition. The concept of race underlay many colonial attitudes towards the colonised. These were coloured by the binary in European thought between the civilised and the primitive. The historical context is therefore crucial to understanding the idea of both the Self and Otherness.

Who determines Otherness? Those in authority generally see themselves as the established Self. They set up the identity of the Self vis-à-vis the Other. This helps to crystallise status and power, and distances those without either. These are not permanent identities nor are they unchanging. Even the criteria by which they are known can change.

The identity of Otherness was not restricted to people that came from different geographies and cultures. It could arise, and sometimes to a startling degree, within the same society. Since societies are stratified, socially and culturally, divergence ranges in aspect. Among these are environment and location, economy and technology, systems of kinship and inheritance, and concepts of belief and worship: in short, the constituents of what we call culture, the pattern of living.

Because of these differences, the existence of the Other was, and is, inevitable. But what is historically valuable is to observe how these differences shaped both the Self as well as the Other. The relationship was not inherently hostile, although in practice it sometimes could be; alternatively it could be mutually acceptable. Where there is competition, there, inevitably, the stronger treats the weaker differentiated one as the Other.

The presence of the Other was noticed millennia ago, almost wherever the processes of thinking are recorded. It was often conceded in subtle ways. One way was through argument, something we all love to do, familiar to every philosophical tradition, and often linked to the exercise of logic. It hints at something akin to the dialectical method. The view of the opponent is presented and then countered by that of the proponent, followed perhaps by a solution. It is more familiar to us as the procedure of purvapaksha, pratipaksha and siddhanta. It revolves around the views of the Self and the Other. Knowledge however is not fixed as there is always the possibility of new evidence and fresh methods of enquiry. Therefore constant questioning was a necessity.

The presence of the Other, whether in person or in the form of contradictory thought, has to be recognised as normal to both the living and the thinking of any society. A society has to accommodate the Other, if need be through argument and discussion, and if no resolution is forthcoming then by agreeing to coexist. Our current impatience with the Other looms over us in so many ways. It is most vocal these days in the connect between religion and society. I would therefore like to take up three examples from our pre-modern history and comment on both past and present perceptions of the Other in the three examples.

But before I do that let me clarify briefly how some of us as historians analyse the interface between society and religion. This is important since neither the kinds of societies in which we live, nor the kinds of religions we practice, are accidental inventions. They are consciously thought-out choices and we have to understand them as such. I for one, see religion as expressed in two forms, informal and formal. Informal religion is that of the individual whose choice of whom to worship and why, is a free and personal decision. More often, however, the decision is made for us through the link between religion and social identity, especially among the elite.

Formal religion is when a belief and practice accumulates followers who identify with it, and it imposes codes of belief and social practices specific to the identity. It establishes institutions in society that give it authority and increase its supporters. The more obvious institutions train priests and monks, administer regular places of worship, organise donations, search for a guaranteed patronage, maintain formal rituals and texts, and encourage a crystallisation of orthodoxy. This latter becomes the font of the religion and is acknowledged as such by society.

New religions often begin informally. With increasing social support they take on formal aspects and establish institutions to propagate their ideas. When they succeed, their visibility takes the form of monumental structures such as viharas, temples, mosques, churches, ashramas, mathas, madrassas, convents, khanqahs, gurdwaras, and suchlike. When this happens it is a sign that the function of that religion is not limited to personalised belief and informal worship, but that it is now in the public domain as a powerful agency involved in social and political policies. At this point the interface between religion and society turns complex.

Socially and politically powerful religions root their codes in a claim to orthodoxy. This is when the Other takes form as a social entity either singly or as more than one. The Other dissents from the orthodoxy and has its own formal belief and organisation evolving from the dissent. Orthodoxy has a choice: dissent can be excluded as contrary or placed in juxtaposition to other sects, or even at some later date, assimilated. Historical change however can alter these relationships. Religions as practiced in India tended not to be monolithic or uniform across the region. In pre-colonial times, social concerns of a religious nature and religious identities were expressed more frequently through sects. These spoke to the larger number of people and less to the limited elite. It is crucial therefore to locate the section of society to which a sect speaks and whatever change both sect and public undergo.

Cultures, we must remember, never remain homogenous and unchanging. There is no pristine, unalloyed culture that continues as such throughout history. Every culture mutates or moults, either through its own historical evolution or in proximity to new elements. That it has multiple roots and multiple branchings-off ensures its immortality.

That said, let me turn now to my examples.

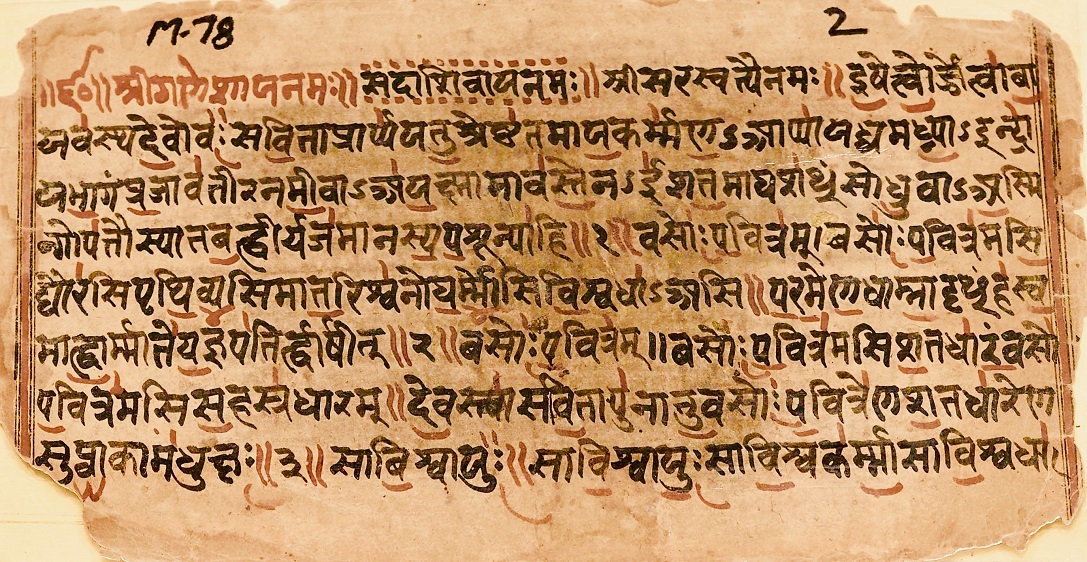

I would like to begin by discussing an example of the Other, from back in the second millennium BC and through to Vedic times. The dominant religion was that of the Vedas as practiced and taught by brahmanas, and thought to be unique to them. The texts however, refer to the presence of others as well. Yet, the popular view seldom concedes this presence since it argues for the existence of just the one dominant culture. The story from the side of the Other remains largely uninvestigated.

The Rigveda refers frequently to two distinct categories of people, the arya varna and the dasa varna. The arya, from which Max Mueller invented the word ‘Aryan’, were those that were respected as persons of status, who spoke Sanskrit correctly, and followed the Vedic religion. Language was the key to identity and it incorporated status. The identification of Aryan became axiomatic in the nineteenth century when race was a primary factor in the colonial understanding of the colonised. The idea of an Aryan race arose from equating the cultural idiom of language — the Aryan speech — with the altogether different factor of biological birth. The identity of race determining a culture anywhere in the world was discarded half a century ago.

We know about the culture of the arya from detailed descriptions in the texts of the Vedic corpus. But who then was the dasa? Evidently the Other of the arya, since the term is often used in that sense. Not unexpectedly, the first distinction is that of language. Those that cannot speak the Vedic language correctly or at all, are dismissed as mridhra–vac, of hostile or incorrect speech. In later texts those who speak incorrectly are the mleccha. Much fun is made of those who invariably replace the ‘r’ sound by the ‘l’ sound. These mleccha were the inhabitants of the Ganges plain because this sound replacement occurs in this region for many centuries. In the inscriptions of the Mauryan king Ashoka for example, those that were inscribed in this area use the sound replacement, so what is elsewhere written as raja is here written as laja. If everyone was in origin an Aryan speaker, such mistakes would have been unlikely.

Language is an immediate identity. What were the other unambiguous differences? Since the dasas practice a different religion, they are called adeva, without gods. They do not perform the required yajnas / ritual sacrifices, not even the soma rituals, so it is said that they are lacking in rituals. Worse still they are disapproved of for being phallic worshipers. They indulge in magic, as did the yatudhana and the rakshasa, so they are disliked and possibly a little envied. They are generally viewed as unfriendly, greedy and socially unacceptable.

But there are complications. Some are also wealthy, especially in herds of cattle and therefore are subjected to cattle-raids. Cattle rustling was a known activity. The dasas lived in settlements with stockades. These we are told were attacked by the aryas with the help of the gods Indra and Agni. The dasas are divided into clans / vish, each headed by a chief. The occasional chief is even said to be a patron of the Vedic ritual sacrifices. After all, fees from wealthy patrons are always welcome.

This relationship between the arya and the dasa that is so intriguing has its own history. It begins with the dasas as initially an alien category. But gradually one can infer social divisions within the dasa society, and these vary in their relationship with the aryas. Not all dasas are wealthy. Those that were appear to have been inducted into arya society, whereas the impoverished ones remained in servile occupations.

As usual the women are the more impoverished. Dasi women are treated as chattels and gifted to others by the chief. The dasi remains a commodity in the community. Many work as servants in arya households. This would also be true of the majority of dasas who would remain the Other, reduced to servitude and distanced socially. Curiously, some of the sons of these dasis are given brahmana status and are referred to literally as dasyah-putra or dasi-putra brahmana.

What are we told about these brahmanas? Those that are respected are mentioned by name. The rishi Dirghatamas is consistently known by his metronymic, Mamateya, suggesting perhaps a different kinship system from the usual patriarchy. He was clearly special because he anointed the great raja, Bharata. He married a dasi, Ushija, and their son was the revered rishi Kakshivant whose hymns are included in the Rigveda, and who also took his mother’s name and was called Aushija. Was having a dasi mother just a matter of low status, or a mark of being from a different culture?

The equally renowned sage Kavasha Ailusha was also the son of a dasi. It is said of him that he was driven away from a soma sacrifice by the regular brahmanas because he was a dasi–putra. As he wandered away he recited some verses and the river Sarasvati began to follow him. Seeing this, the regular brahmanas immediately recognised that he was special to the gods, so they welcomed him back, gave him brahmana status, and more, they declared him to be the best among brahmanas. What was his special power that despite being a dasi-putra he was honoured by the brahmanas?

The Upanishads carry the story of Satyakama Jabala who came to the rishi Gautama requesting that he be accepted as a Vedic student. The rishi asked if he was a brahmana. He replied that his mother worked as a dasi in a household where many men came and went, and she could not recall who his father may have been. The rishi replied, that who but a brahmana would have told the truth as Satyakama had done, and he was accepted as a student. The issue is not of the varna identity but the ethical qualification.

Despite having dasi mothers these rishis knew the language of the aryas to perfection since some of the Rigvedic hymns are attributed to them. They were not described as mridhra–vac or mleccha, nor was it said of them, as was said of the great ancestral figure of the Puru lineage, that they came of an asura rakshasa origin. Those dasi–putras that acquired brahmana status were born to the lowest status mothers but were recruited into the highest caste. Is there a hint here of a subtle and new socio-religious interface of a more complex kind that needs further investigation?

One sees in this gradual merging of some aspects of both groups, a modifying of their identities. The dasa has learnt the language of the arya. Does this amount to his having been Aryanised? On demonstrating his superior power, his superiority is acknowledged and appropriated by the arya. Did some of the dasa culture rub off even marginally on the arya? Or was there a more nuanced mutation in both? These sons of dasis are not described as nastika / non-believers, since there seems to be some eagerness to acquire their knowledge. Did this duality, expressed in the conversation between the dasi-putra brahmana and the high status arya, create an elite culture that drew from both sources? The antecedents of these cultures remain intriguing questions.

Let me now turn to my second and very different example: an existing culture gives rise to an alternative Other from within itself. The Other here is not alien but is in disagreement with the prevailing belief and practice. I am taking you now to the late first millennium BC and beyond, into the early ADs. I am referring to the emergence of groups that were jointly called the Shramanas — the Jainas, Buddhists, Ajivikas — and some included the Charvakas / Lokayatas as well.

The Shramanas were opposed in varying degrees to Vedic Brahmanism. They questioned the belief in deities, in the Vedas being divinely revealed, in the existence of the individual soul or atman, and in the efficacy of the yajna / ritual of sacrifice. Brahmanical literature refers to them categorically as nastika, the non-believers. These ideologies of opposition underwent many changes as they meandered their way through history. However, for the orthodox and for the formal religions that were to evolve around Shaivism and Vaishnavism, the Shramanas were invariably the Others.

Apart from their differences of belief, both were competitors for royal patronage. But the Shramanas included among their patrons wealthy merchants, mercantile guilds and craftsmen. This ensured their popularity with wider levels of society. Doubtless it added to their ideological differences. The grammarian Patanjali compares the antagonism between the two — the brahmana and the shramana — to that between the snake and the mongoose. The emperor Ashoka makes repeated pleas for harmony between the various sects. But the point is that there were by now a variety of sects with dissenting views and no religion was uniformly observed and monolithic in its teaching.

In the period from the Mauryas to the Guptas there is a striking presence of impressive Buddhist stupas, and an equally striking absence of temples, a situation that was slowly reversed in the subsequent period. These are indicators of patronage and popularity. It was a time of intense social change with clan societies giving way to caste societies.

It was subsequent to this that the Buddhists and Jainas, projected as dissidents in the early Puranas, experienced persecution. Jainism survived by consolidating itself in particular areas. Buddhism did not, but became predominant in many other parts of Asia. Interestingly every religion in India had by now acquired multiple sects, each seeking its own patrons and recognition. No formal religion was a monolith. The feasibility of differences and their coexistence was recognised, although some among them faced animosity and conflict. But in either case the relationship between sects, whether friendly or hostile was confined to smaller, more localised groups.

The Shramanas established a new personality on the social landscape, namely that of the renouncer in the form of a monk, the bhikkhu. The emergence of these renouncers took on the characteristics of what may be called a counter-culture, at least initially. It was a new kind of Other. The renouncer was distinct from the ascetic. The ascetic went into isolation searching for ways to liberate his soul from rebirth. The renouncer joined a monastic order — a community that lived in parallel to society, observing its own rituals, and identified by a differentiated formal religion. It broke the rules of caste in being celibate, in taking cooked food from anyone as alms, and (in theory at least) in not segregating the avarna, those outside caste. However, the distance from society was not absolute as it accepted patronage from different levels of society, and worked towards a large following of people convinced by their teaching. The teaching was not intended to convert people to a new religion but rather to give them a new ethic to direct their lives.

The monks therefore had a concern with the welfare of society so they remained partially connected to it. Unlike the ashramas — the forest hermitages of earlier times — these monasteries of the Shramanas were organised institutions and their intervention in social life made an impact. Receiving donations of wealth and large grants of land created monastic landlordism, as Max Weber calls it. Their effective interventions in society led to other religious sects establishing counterpart institutions, such as brahmana mathas, and Sufi khanqahs and dargahs. A range of religious sects adopted this institutional form as they do to this day. Some were devoted to scholarship and the study of religious and philosophical ideas, some were involved in meditation, and some with political and social concerns, expanding their degree of Otherness. The Shramanas eventually created their own orthodoxies, but initially they demonstrated the potential of the Other.

The individual renouncer moved across the historical landscape in diverse forms, such as the sadhu, faqir, jogi, in the name of the Other. In a somewhat contradictory way the renouncer opting out of society acquired moral authority within society. One wonders whether this was the reason why Kautilya discourages the state from allowing renouncers to enter newly settled lands. Where the state had a tight control over society, as advocated in the Arthashastra, it exercised the power to disallow dissenting views.

Renouncers voluntarily chose to join the alternative society that gave them a different identity. But a major category of Otherness that we have frequently ignored is of course, that of an imposed Otherness. I am referring to the category of the avarna — the lowest castes, those outside caste, and the untouchable. This was the creation of the upper castes. It ensured a permanent supply of bonded labour, as well as a category of people who could be forced to do the work that the rest of society refused to do. The imposition was so oppressive that it disallowed opposition and ensured an unchanging continuity. This is yet one more process of creating the Other, and we have to ask who is creating it, for what purpose, and who is being forced to conform to it. Those that have Otherness imposed on them have to question the legitimacy of the imposition.

My third example is a rather complicated one. I shall now speak about the Other in the context of the many Others, and the many Selves. I am again jumping another millennium and referring to the fifteenth-sixteenth centuries AD, a remarkable period of the Indian past especially from the perspective of the history of religion. There was by now an even greater social mixture than ever before. This is reflected in the teachings, the poems and the life of the time. The emperor Akbar was not a flash in the pan, creating new religious trends. I shall be speaking of those less exalted but whose activities as the Other went further.

My example is one facet of the Bhakti movement, a movement that arose in every part of the sub-continent under diverse sants. Initially these were the Other in the context of existing religions. Together with these were the Sufi schools that came from Central Asia and settled in India, forming yet more Others, crucial to breakaway sects. Given this interface of cultures, a spectacular efflorescence of religious teaching and expression followed, affecting many levels of society. This shaped the practice and belief of those whom we have now brought together under the single, uniform label of Hindu; it also shaped the belief of those who were at that time called Yavanas, Shakas and Turushkas, and for whom we today use the single, uniform label of Muslim. I shall try and speak of them as they were spoken of in their own time.

Neither the Bhakti sants nor the Sufi pirs were founding new religions. They were trying to liberate religion from orthodoxies and jaded conventions enforced by those who had authority over formal religion. Significantly the teaching of these many Others was open to any person or group. The nature of their Otherness varied according to whom they were addressing as the Self.

The previous religious identities of their followers were therefore irrelevant, nor did they endorse caste conventions. The deity worshipped could be an abstract idea or an icon. The teaching was informal as were the scant rituals. Among the sants were Kabir, Ravidas and Dadu who, as coming from the lower castes were searching for their utopias. Ravidas had a vision of a future city where there was to be no social inequality, so no sorrow, and therefore called Be-gam-pura. They saw themselves not as a single, but as diverse Others although connected in aspects of their teachings. The diversity is evident not only in the teaching of these sants but also in that of Lal Ded and Nanak. Unlike the first three that I have mentioned, Lal Ded was a Shiva bhakt, yet this did not stop her inspiring the Sufi poet Sheikh Nuruddin, popularly known as Nand rishi. Nanak’s verses drew from the Sufi teachings of Baba Farid and others. All this deeply enriched the thought of the times.

Then came the cloud-burst that completely immersed so many. This was the immense popularity of Krishna bhakti projected through devotion to Krishna and the worship of Krishna and Radha. As one of the idioms of the sixteenth century it needs further analyses. The Bhagavata Purana and Jayadeva’s Gita-Govinda point to its importance among Vaishnava sects. However, a new impulse came with Krishna bhakti becoming the focus of another set of poets, speaking from distant places and cultures, also referred to as Bhakti sants. These were Chaitanya, Surdas, and Mira among others.

Together with these and equally important were their fellow worshippers and poets from another variety of religious and social backgrounds. Among them were Ras Khan from a wealthy zamindar family, and Abdul Rahim Khan-i-Khanan who held high offices in the Mughal administration. Disciples from various religions clustered around the sants. Haridas was the name taken by an important yavana disciple of Chaitanya. Sufi poets such as Bulleh Shah, Malik Muhammad Jayasi, and Sayyad Mubarak Ali Bilgrami, to mention just a few, wrote exquisite poems of adoration to express their Krishna Bhakti. Fortunately these are still sung as part of classical music and dance, and on other occasions. Inevitably it was said of them that these Yavanas were attaining moksha through this bhakti.

What I am saying is nothing new. It is all well known. But it seldom enters our discussion when illustrating some forms of Bhakti as the Other. The question that has not been answered adequately is why there was such an upsurge of Krishna bhakti at this particular time, drawing in such a variety of people from a range of religious traditions. What were the floating ideas and changing social forms that encouraged this?

Another obvious question is, why did so many Muslims, and not inconsequential ones at that, turn their creativity towards Krishna bhakti. Modern historians have called them Muslim Vaishnavas, but they did not call themselves that. They preferred to call themselves Krishna bhaktas. The difference is very significant. In present times, we overlook the fact that non-Muslims in those days only occasionally used the label of Muslim, a label that we use uniformly today. In those days they were more often referred to as Yavanas, or Shakas or Turushkas. These labels are ethnic and not religious. They also link up interestingly with earlier history. Yavana was used for the Greeks and those who came from the West, as also did the Arabs. The Shakas were the Scythians from Central Asia. Turushka was among the names for the Kushans, also from Central Asia. Shaka and Turushka were historically authentic names therefore, for the Turks, Afghans and Mughals, who came from this region. The Indian of a millennium ago saw them linked to the earlier people who had come from the same region.

However, they are occasionally referred to as mlecchas, used sometimes in a derogatory sense or as just a passing reference to difference. For example, in one inscription from the Deccan, the Delhi Sultan, Muhammad bin Tughlaq after a successful campaign in the area, is described by the local defeated side as a dreadful man who killed brahmanas, destroyed temples, looted farmers, confiscated the land granted to brahmanas, drank wine and ate beef. This was now to become the stereotype description of a Muslim when a negative projection was required.

But there are also Sanskrit inscriptions from elsewhere that make a different assessment. One from Delhi issued by a merchant, also during the reign of Muhammad bin Tughlaq, is full of praise for the Tughlaq rulers, describing them as the historical successors to the Tomar and Chauhan Rajputs, with a passing reference to one of them as mleccha. Obviously in this case the term refers to someone who is different, as no one would dare to refer to the ruler in derogatory terms.

Yavanas, Shakas and Turushkas, who were previously Muslims, were included in the ranks of the Other in some texts and by some authors, conforming to earlier historical precedents. What complicates this particular Otherness is not only its own origins but also that it has many Selves. For instance: was every Muslim viewed as a mleccha by upper-caste Hindus? Yet there were politically significant marriage alliances among the highest royalty. The Kachavaha Rajputs, claiming high caste Suryavamsha kshatriya status, gave their daughters to the Mughal royal family. Some of the most important positions in the Sultanate and Mughal administration were held by the upper-castes — Rajputs, brahmanas and kayasthas, and the Jainas. The social distance would presumably have also depended on caste. It is likely that those lower down the social scale would have mixed more easily on all sides. But the distancing of the avarnas by upper-caste Muslims did not change even when they converted to Islam.

The Krishna bhaktas that I have been speaking of were viewed as the Other, by two categories of Selves. Those that were born Muslim and became Krishna bhaktas were strongly disapproved of by the qazis and mullahs of orthodox Islam, and equally so by orthodox brahmanas. This was so until such time as it became helpful to the formal religions to incorporate some of the teachings of these bhakts. This indicates that both the Other and the Self have to be carefully defined each time either is referred to. This might be a necessary exercise in clarifying identities, and especially where they overlap. Not all Muslims were identical as indeed nor were all Hindus.

An interesting comment on this situation comes from a sixteenth century Sanskrit text, the Prasthana-bheda of Madhu-sudana Sarasvati. He states that the teachings of the Turushkas, have to be aligned with those of the Charvakas, Jainas and Buddhists. And why? Because they were all nastika /non-believers. For the latter three – Charvakas, Jainas, Buddhists – this is a repetition of what was said of them by brahmana authors in the much earlier past. To these three Madhusudana Sarasvati adds the fourth, the Turushkas. The three did not believe in any deity, therefore were rightly called non-believers. But the Turushkas did believe in a god, because they believed in Allah. But since Allah was not of the Vedic or Puranic pantheon, he was unacceptable, so they too were nastika. Interestingly, the author also refers to all four of them together as mleccha.

Let me try and make a few final points. I have taken only three historical examples, each separated by a millennium. These were groups that were initially projected as Others. From the simple duality that we began with, we arrived finally at layers of Otherness and its multiple manifestations. The changing historical context also required them to change. Some were opposed, some were subsumed into the dominant society, and some were accommodated as yet another juxtaposed sect. We need to know what social relationships emerged from their presence. How were they viewed? And equally, how did they view these social relationships? Can we think of projecting history from the perspective of the Others?

This would be a necessary corrective. We currently view our past cultures only through the lens of the established Self in each period, be the Self Hindu, Buddhist, Jaina, Muslim or Sikh. Or else, we inflict our present-day stereotypes on the past without examining their viability. We give weightage to the texts of those in authority, be it royalty or sections of the elite, ignoring other, multiple differentiating views. In defining our traditions and our cultural inheritance, this multiplicity has a significant presence, both in what was accommodated and in what was contested, and why.

Understanding the interface between religion and society requires us to recognise that both the formal religions, and the more informal evolving sects, were being transformed by it. New thinking arises either to conform or to dissent. The one cannot be understood without the other. All formal religions and settled societies have Others, especially when identities are strongly demarcated. Such demarcations seem to receive more emphasis when religions are used to define political identities and social gradations. This we have to be aware of.

Religion is only one marker of identity and is conjugated with other markers — occupation, caste regulations, language, and so on. This makes it essential to relate each religion to its larger social constituency together with whatever change it undergoes. Why do some religious sects as the Other became powerful new castes, whereas some lose out — as for example, the Lingayat in the first case and the Kabirpanthi in the second. Since societies change so do religions linked to these societies.

Religious identities are not formed in isolation. More often than not, some are viewed as heritage and some as a reaction to the Other, be it from within society or from outside. The process is a kind of cultural symbiosis that gives an imprint to Indian religious and social articulation, and the imprint differs from other historical societies. This we have yet to explore.

It is not enough to point out that there has always been an Other or Others, as there have been many Selves. The reason for each has to be analysed in the context of its mutating identity. The Other can be a voice of dissent or of animosity, characterising differences that are altered by historical change. The acknowledgement of dissent is essential because the nature of dissent also reflects our own self-perception. Many sects, either juxtaposed or distant, represent complex and divergent thoughts that have in the past sculpted the Self and the Other. This allowed a free play of belief, emotion and enquiry, such that they invalidate our present-day monolithic, binary identities. It is to this that we owe many moments of spectacular thinking that are evident in the dialogues between the Self and the Other in our past.

The text is a lightly edited version of the Nemi Chand Jain Memorial Lecture delivered by Prof Thapar at Delhi, on August 16, 2019.

Image courtesy Wikimedia Commons

Image courtesy Wikimedia Commons