Speculative fiction is, for me, the silvered back of the mirror; its mercury melts unless you peer into it. For it is of the imagination. Its terrors, beauty and rapture require you, the reader, to recognise its private world, enter and make it your own.

Its mythic, mirage-like quality gifts the writer unconstrained freedom to invent entire universes teeming with life of all sorts. This freedom is the quality I most cherish about sci-fi and cli-fi (climate change fiction). To shine the light of a dark sun into mysteries that reveal more wonder while critiquing social structures that we homo sapiens, the wise ones, have created. Speculative fiction can be a morphing, hold-all genre; it is frequently the literature of metaphor and metonym.

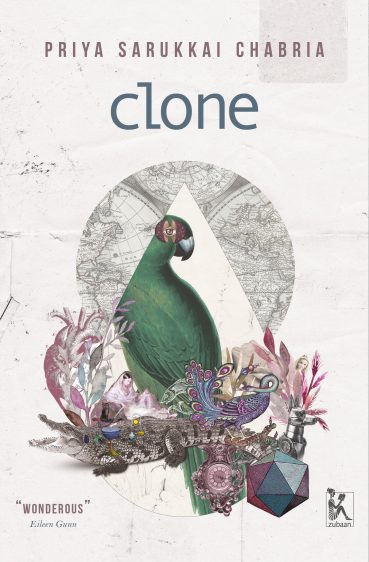

This often plays out as subversive, irreverent, rebellious stories. Though set in the 24th century, my novel Clone’s narrative reflects current concerns about India, and elsewhere. For instance, the suppression of plural histories and disregarding a long-standing Indic tradition of debate that is foundational for a democracy.

For me this is a genre of hope — even when it projects dystopian futures which are early warnings. Speculative fiction is, consequently, a narrative of contemplation and creative questioning. In every sense of the word.

Here’s where the fun comes in — and the challenge for both writer and reader. The genre demands deciphering made-up words, portmanteau words and worlds through scattered clues. This militates against passive reading. For instance: What’s a flitting glass butterfly? What are pirouetting rainbows? Easy to imagine. A fritjith crocodile? A siffreen pond? The Drug? Perhaps a trifle more challenging. More inviting is how I see it, more spacious for the reader’s imagination to inhabit.

My novel ruminates over selfhood, sexuality and creativity. The Clone lives in a future where sex is forbidden for the majority, which, I guess in retrospect, can be read as a sliding metaphor for the silencing of female desire and violence towards women. Then she awakens, a startled flower, to experience volatile emotions and desire. As questions stream forth: Do the shaming patterns of the present penetrate her mind? How does the erotic experience manifest in her song of selfhood? Is possessiveness an inevitable part of pleasure?

Clone ranges over time too, from an inset story set in 1500 BC during an early phase of Indo–Aryan migration to our protagonist, the Clone’s life spiraling in the 24th century. I deploy this ambitious scape to question what it means to be human. Where are we heading? What rights do we have over the resources of this planet and the lives of countless other creatures? Hopefully, our impulse against ecocide, towards transhumanism — which is defined as ‘an intensification of humanism’ — moves us in the direction of compassion.

Simultaneously, we are moving towards more dependency on and implants of Artificial Intelligence, AI. Speculative fiction opens us to querying posthumanism, which promotes the idea of the human increasingly embodying and embedded in a technological universe. We are slowly but surely morphing from homo sapiens to homo digitalis – to borrow the term from AI guru, Toby Walsh. We already inhabit a world that includes cloned sheep and simians, humans with legs of carbon fiber and remote-controlled limbs. What does this mean for us as a species? Scenarios unfold from the terrifying to the illuminating.

Prologue

I am a fourteenth generation Clone and something has gone wrong with me.

Not that my DNA is altered, not that I am a mutant. Not that any function need be eliminated. It’s nothing obvious. It’s terminal, and secret.

Let me put it this way: I remember.

My consciousness is morphing in an unplanned way. I’m also very lonely. It’s not pleasant to have so much memory and no one to share it with. I don’t dare. Which is why I’ve decided to keep a diary hidden as a cellchip in my system. So far undetected; so far, so good.

The first strange thought I had was of a dodo. It was the last dodo and I was it. This thought-experience rushed with adrenaline. I was feathered, flightless and fleeing.

The thought passed. Others followed. Each disconcerting, each more detailed. I thought I was going insane. I went to check out with my Elder, the thirteenth generation Clone. But I was late. My Elder was a saintly member of our community who had recently signed up for the Exhaustive Organ Transplant Scheme. I reached a liver, one eye, two feet, three metres of skin and perfect clavicles.

The only option left was to research my Original, to check out if these visitations have something to do with transmutations in her neurological circuitry. Or maybe something was overlooked in the cloning process. This is not supposed to occur. But neither are we to carry memory traces or epigenetic information beyond the second cloning. We are replicated by Soft Coral Code transmission, as more and more of the same.

Ours is an open society. Everyone—Originals, Superior Zombies, Firehearts and Clones—has equal right to access information. Nothing is prohibited, but there are consequences. However, I have decided to take the risk. Initial investigations suggest my Original was a writer living in the late twenty-first century. Maybe she should never have been cloned.

It’s curious. I’m getting into what I suspect was the Original’s life, or possibly her writing life, depending on how one wants to view it. These are strange ideas for a Clone. But strangest of all: I remember.

My consciousness has morphed.

[…]

From The Sentence, set in the Vijayanagar Empire

…How many months ago did I first lay eyes on the wench? When I have so little time before me that each breath chokes, how is it that time past runs before my eyes like a swollen stream, and all I can remember are moments? I remember clearly: my duty was over, the second shift was to begin. I was standing at the Muslim-style watchtower, the one to the west, and I looked down.

The richest and most famous courtesans were sporting in the bathing tank that lies to the northwest, and we guards always look at meat meant for the immortals. Why not? Being a palace guard has advantages. That day our Monarch had wished for pleasures other than those provided by His zenana, and these public women were summoned. He was late. The courtesans were in the water, playing ball, singing, vying for the best position, and there she stood on the steps of the bathing ghat, holding the umbrella, not deigning to get wet though it was obvious that her mistress was bathing.

To tell the truth, I didn’t notice her till after our Monarch made his choice for the night: Gangadevi, renowned for her expertise in the four kinds of poetry and playing of the veena. For it is well known that He is a scholar and poet Himself. On His way up the steps of the bathing tank He noticed her standing aloof and playfully threw a handful of water at her. My eye followed His action. The handmaiden He had singled out for an instant, she I wanted.

By the time the third watch was over I found out to whom she was bound. We guards have a way of sharing information. She was Gangadevi’s umbrella-carrier. I gathered my money, put on my best clothes, had myself massaged with sesame oil and perfumed with a pod of sandal paste before I strolled down Soolai Bazaar Street, where the courtesans and rich merchants live, their grand houses separated by walls of plastered rubble. Gangadevi’s establishment is well known. Her house front is covered with paintings of panthers, tigers, lions and peacocks. Gangadevi’s velvet-draped couch placed on the street side was empty: she was busy. But Vanithamma was there, leaning against the couch, chewing betel nut, and looking at the sky.

On the very first night, she told me about the Monarch’s bedchamber, for we male guards are not allowed beyond the fourth enclosure; eunuchs and women warriors protect the interiors. She had escorted Gangadevi into the palace interior just recently. The bedroom’s dome is gold-plated, gems in heart-shaped designs encrust the walls, around the pillars wind streams of emeralds and diamonds, the lion-paw legs of the bed are of gold, seed pearls run as railings a span high, the mattress is covered with black satin, and overhead hangs a canopy of embossed gold. For His feet are four cushions of black Mecca velvet, tasselled with pearls; His mosquito net is framed by rods of carved silver; His spittoon is made of gold. She spoke of such opulence that I felt dizzy and my bones seem to drip.

The wench said that one day she will sleep on that bed; she told all this to me even as we were shifting positions. After I finished, I twirled my moustache and told her not to get grand ideas just because one of the Monarch’s junior queens was a courtesan he knew in his earliest youth. She laughed. She was disregarding me, a second-level guard. I left my mark on her shoulder. She would not agree to see me for three weeks though I agreed to raise her fees.

By now they should know who is to behead me at dawn tomorrow…