The how and why of the farmers’ long march to Mumbai

Over the past six days, India has slowly woken up to farmers’ distress—and their resistance. On 6 March, about 20,000 farmers from various parts of the state mobilized by the CPI (M) affiliated All India Kisan Sabha gathered at Nashik in north-western Maharashtra to begin a 200-km march to Mumbai, the state capital. The plan was to indefinitely gherao the Assembly while the Budget session was on and demand immediate resolution of the life-and-death issues facing farmers. By the time the march entered Mumbai on 12 March morning, it had swelled to over 50,000 people, the government was scrambling to deal with the red tide sweeping in, political parties were falling over each other to show support, and residents of the commercial capital of India were wondering what they had been missing all this while.

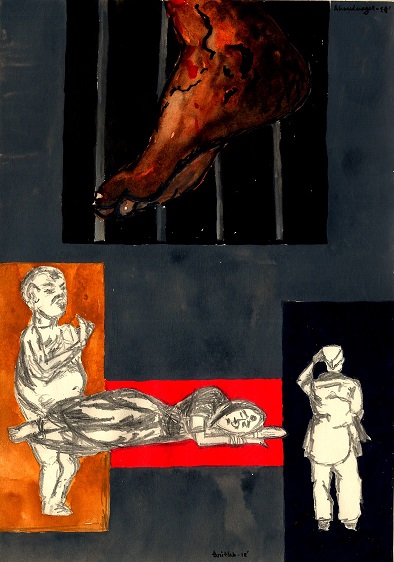

Like everywhere else in India, farmers in Maharashtra are reeling under the double whammy of falling incomes and rising indebtedness. In 2017–18, agricultural economy of the state shrank by 8.3 per cent, according to the state’s Economic Survey tabled in the Assembly on 9 March [2018]. The Survey predicted that cereal production will dip by four per cent, pulses by 46 per cent, oilseeds by 15 per cent and cotton by a whopping 44 per cent in the current year’s kharif season. Cotton is a major crop in the state, but a massive infestation of the standing cotton crop by the pink bollworm has destroyed crop worth Rs 15,000 crore, affecting nearly 20.36 lakh hectares—that’s 50 percent of the area under cotton. The Economic Survey also had a dire prediction for the forthcoming rabi crop—acreage is down by 31 per cent, and production is expected to fall by 39 per cent for cereals, six per cent for pulses and 60 per cent for oilseeds.

All this is just the current calamity. Distress of the farmers has been building up over the years because of rising input prices and falling returns as they fail to get remunerative prices. Indebtedness is another dimension of the same problem. Last year, the BJP government had announced a farm debt waiver worth Rs 34,022 crores to supposedly benefit 70 lakh farmers. But the finance minister admitted in his budget speech that just Rs 23,102.19 crores have actually been sanctioned for 46.4 lakh farm households, and further, that only Rs 13,782 crores have actually been disbursed to 35.7 lakh farmers’ accounts.

But the core of the farming crisis lies in the fact that farmers’ incomes are not at par with what they are spending to raise their crops. A Niti Aayog paper admitted that according to a government committee on agricultural prices, farming output prices have increased by just 6.88 per cent between 2011–12 and 2015–16, while the prices they pay for goods and services have increased by 10.52 per cent.

Another factor is the steady decline in landholding size over the years. In 1971, the average landholding size in Maharashtra was 4.28 hectares owned by 49 lakh landholders. This has slipped to 1.44 hectares owned by 137 lakh landholding farmers. About 78 per cent of these farmers are “small and marginal”, that is, they own less than 2 hectares of land.

Despite it being considered an advanced and rich state, Maharashtra has just 25 per cent of its cultivable area under irrigation. Thus, with three-fourths of farmed area dependent on rains, and the increasingly erratic monsoon, farmers are constantly facing a water crisis that destroys their budget. A bizarre feature of this crisis is that sugarcane, which covers just 4 per cent of the state’s sown area consumes 71.5 per cent of the water consumed for irrigation.

Another key factor fuelling the farming crisis is the refusal of the state government to speedily implement the Forest Rights Act (FRA) that gives tribal farmers land rights over forest lands that they have cultivated for years. Maharashtra is lagging behind several other states in such distribution of land right deeds (pattas). This has angered tribals in the Thane belt in north-west Maharashtra and the Vidarbha region.

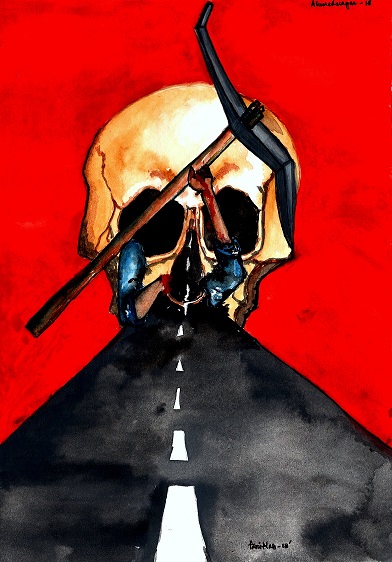

Faced with this immense crisis, Maharashtra has seen a spate of farmers’ suicides over the years. Just last year, 2,414 farmers reportedly committed suicide despite the state government’s debt waiver. But, that’s just one way the hapless farmers found escape from harsh life. All over the state, thousands of farmers found new strength and hope in the collective protests organized mainly by Left organisations, led by the AIKS.

Two years ago, on March 29 and 30, 2016, the AIKS had led an unprecedented one lakh-strong peasant siege for two days and two nights at the central CBS square in the heart of Nashik, which had paralysed the city. Maharashtra’s BJP Chief Minister Devendra Fadnavis gave assurances to AIKS, but since these were not fulfilled, the AIKS-led a 10,000-strong ‘coffin march’ in Thane city in May 2016 to focus on the issue of peasant suicides.

Then, in October 2016, over 50,000 adivasi peasants gheraoed the house of the Adivasi Development Minister at Wada in Palghar district for two days and nights. Written assurances on issues like FRA and malnutrition-related deaths of adivasi children were given. Meanwhile, AIKS held protest actions at Aurangabad in the Marathwada region in May 2016, and at Khamgaon in the Vidarbha region in May 2017 on issues of drought, loan waiver and remunerative prices.

A historic united peasant strike was held from June 1–11, 2017, led by a coordination committee of farmers’ organisations. On June 11, the state government was forced to hold talks with the Coordination Committee and agreed to give a complete loan waiver to the peasantry. But the deceptive loan waiver package of Rs 34,000 crores that was announced imposed several onerous conditions that would prevent a great majority of farmers from getting any relief. This betrayal sparked massive joint protests—fifteen large district conventions in July, in which over 40,000 farmers participated, followed by a state-wide chakkajaam (road blockade) on August 14 in which over two lakh farmers blocked national and state highways at over 200 centres in thirty-one districts of the state. Finally, on 16 February 2018, at an extended meeting of the AIKS Maharashtra State Council at Sangli on February 16, attended by over 150 leading activists from twenty five districts, the decision to hold the Long March on 6–12 March [2018] was taken. A vigorous campaign was carried out throughout the state and it received enthusiastic response all over.