There are many objects from the past that have survived into the present. These not only tell us about the past but often contribute to how we shape the present. Of each, we ask the usual questions and construct a narrative of who made it, where, and for whom. Many find their way into a museum where they are minimally described, and their narrative more or less left to the imagination of the viewer.

I would like to consider a rather different kind of object from many centuries ago that was periodically chanced upon and puzzled over. It occasionally carried a statement by a royal figure, but for many centuries in between, it was disregarded or forgotten. It is now one of our prized sources of history. I am referring to the pillar of Ashoka Maurya that currently stands in the Allahabad Fort.

It was probably originally cut, sculpted and polished at Chunar (near Varanasi), from where a number of pillars were quarried. The sculpting and the polishing were done on site and, possibly, even the engraving. It was engraved on the orders of Ashoka Maurya and first erected at Kaushambi, a city of political importance in the neighbourhood of what is now Allahabad. Some centuries later, it was shifted to its present location in the Allahabad fort. Its surmounting capital was, possibly, a seated lion, now lost.

The pillar of Ashoka at Allahabad Fort

The pillar of Ashoka at Allahabad Fort

The pillar carries six of the seven Pillar Edicts of the emperor inscribed in the 27th year of his reign, c. 240 BC. The Edicts are carefully engraved around its circumference and form a substantial document. They are some of his musings on propagating the dhamma as a system of social ethics which was, to him, central. The language is the widely spoken Prakrit and written in the Brahmi script used at the time. Below these edicts are engraved a couple of more inscriptions: the Queen’s Edict, an order that the donations of the Queen be recorded; and what has come to be called the Schism Edict. The latter states that those monks and nuns who cause dissension in the Sangha are to be expelled. Had this been all, the pillar would have been a major historical source. But there is much more.

In about the fourth century AD, some six centuries after the initial edicts were engraved, a long inscription recorded the achievements of the Gupta king, Samudragupta, on the pillar. The statement was composed by the poet Harishena whose family served in various senior capacities as officials at the Gupta court. The text was composed in Sanskrit and not in Prakrit; and engraved in the Brahmi script but of the Gupta period, no longer identical with Ashokan Brahmi. Whether or not the earlier Ashokan Brahmi could still be read has been a matter of controversy. Scripts, like languages, do change. The engraving of this inscription cuts a little into the earlier one, suggesting either that the earlier one could not be read, or was disregarded.

By the time of the third inscription of historical significance, we are told categorically that the earlier two could not be read, so no one knew what was intended by the pillar. This was the Mughal emperor Jahangir’s statement giving his genealogy, going back to his Central Asian forbears, composed in Persian and written in a fine nastaliq script. Scattered across the pillar is the graffiti of lesser people who recorded their presence with their names, rather like the scribbles of contemporary tourists on monuments. These consist of the names of local rajas and visitors, including a one-liner of Akbar’s minister Raja Birbal.

So we have a historical object that has survived for three millennia from the first millennium BC to the start of the third AD. Its uniqueness comes from the documents it carries written in three distinct languages and scripts, and what they tell us. Each set of inscriptions concerns a king, who is entirely different from the other two. Yet the second and the third must have been convinced that the object had some intrinsic historical power, which prompted their inscriptions despite their not knowing the authorship of the previous ones. The message of each king was entirely different, with a different function and intention. The pillar went into a kind of oblivion for many centuries, till the script of the two earlier inscriptions was deciphered a couple of centuries ago and their authors eventually identified. The realisation grew that the pillar was indeed a historical palimpsest, and that the later contributors may have seen it as encapsulating a form of historical consciousness.

My concern is not with this aspect of its function. I would like to present the pillar through the inscriptions as a pointer to how some Indian rulers saw the then-known world, and at specific times.

Let’s begin with the edicts of Ashoka. The opening statement reads: devanampiye piyadassi laja hevam aha / the beloved of the gods, Piyadassi, the king, speaks thus. It then mentions the date when the edict was issued as twenty-six expired regnal years. One recognises a hint of similarity with the opening of the Achaemenid king, Darius’s inscriptions: “thus says the king Darius.” But sometimes this makes for a more grandiose formulation, as when he says: “I am Darius the great king, king of kings, king of countries containing all kinds of men, king of this earth far and wide…” There is less grandiloquence in the opening lines of the Mauryan king. Many royal inscriptions tend to be self-congratulatory but in the case of Ashoka, such sentiments are low key. He sees his achievement as the propagating of dhamma far and wide.

It was once thought that the Achaemenid rock inscriptions of Iran, such as those at Naqksh-i-Rustam and Behistun, inspired Ashoka. The pillar as an architectural form surmounted with a capital, was noticeable at Persepolis in Iran. But inscriptions and pillars were not rare in the ancient world. Other similarities with Iranian forms were more pertinent, such as certain decorative features. Mention has been made of the abacus with its decoration of a scroll of lotus and honeysuckle, not to mention acanthus leaves. Whether this was an influence is debatable, but the designs were familiar.

Given that Gandhara in north-west India and the Indus region down to Sind were for a while part of the Achaemenid domain, and subsequently there was proximity between the two empires, the Seleucid and the Mauryan, it is rather surprising that the Mauryan settlement adjoining Taxila (Bhir Mound) shows little presence of Achaemenid features. However, these features are present further afield in the use of Aramaic in some Ashokan inscriptions. Later sources mention Tushasp as the governor of Saurashtra and this is a distinctly Iranian name. Historically these borderlands, from the Hindu Kush Mountains to the coast of Makran, are characterised, as are many frontier regions of the ancient world, by the alternating domination of the powers on either side. The proximity of western India to Iran, in more than a literal way, is a historical factor that we often tend to overlook.

But to return to the edicts, the Mauryans had had a close relationship with the dynasty that ruled in Iran subsequent to Alexander. This was the Seleucid dynasty. Whether the young Chandragupta Maurya met Alexander, as asserted in some Greek sources, does not make much difference. More important, the Mauryans had a distinct interest in the politics of west Asia and the eastern Mediterranean.

When Seleucus Nicator campaigned against Chandragupta Maurya, the advantage seems to have been with the Maurya. Seleucus ceded, according to the treaty, territories in eastern Afghanistan in return for 500 war elephants. Elephants had clearly made a deep impression on Greek generals since even Hannibal, took them up to the Alps, where unfortunately the tropical animals could not survive the cold. The intriguing clause in the treaty was the epigamia – some say it referred to a specific marriage alliance between the dynasties, and others maintain that it was the legal sanction for Greeks and Indians to intermarry. Did new communities emerge from inter-marriage? There were communities of Greek speakers in Afghanistan since some of Ashoka’s edicts were rendered into Greek. Incidentally, this concern with accessibility was extended to the Persian Aramaic speakers as well.

The Pillar Edicts were largely devoted to explaining dhamma and its propagation. It was a social ethic conducive to encouraging a harmonious way of life. The dhamma-mahamattas were the officials concerned with its propagation. Apart from the Mauryan domain, they also had to go to the kingdoms of the neighbouring areas to continue the propagation. This must have encouraged an active interest in what was happening in neighbouring countries. Ashoka wanted the understanding of dhamma to spread throughout the world, but the world as he lists it did not go far beyond the Mediterranean. Mention is made of these activities as early as in the Rock Edicts a dozen or so years prior to the Pillar Edicts. The references in the Pillar Edicts are therefore a continuation of the earlier activities.

Hellenistic sources mention visits to India by ambassadors from these kingdoms. The best known among them was Megasthenes who, as a friend of Seleucus Nicator, is said to have visited the court of Chandragupta. Some of his compatriots, however, thought that he collected his data from interviews and hearsay and not from a personal investigation of the Mauryan capital.

An ambassador, Deimachos, is said to have come later as ambassador from Antiochus I, to the court of Chandragupta’s son known to the Greeks as Amitrochates, otherwise Bindusara. The Mauryan king asked Antiochus to send some sweet wine, dried figs and a sophist. He was informed that the first two could be sent but not the third for the obvious reason that the sophists were free men, not slaves. It is interesting, if true, that Ashoka’s father – said to be a patron of the Ajivikas – should have asked for a Greek sophist, an intellectually provocative demand. One wonders what he had heard about the sophists. Greek sources also mention a request for aphrodisiacs. The nature of the gifts suggests a cosy friendship!

Although Ashoka does not refer in detail to the kings of west Asia in his Pillar Edicts, he does so in the Rock Edict XIII. These were the five Yona-rajas or Greek kings. Yona or Yavana, derived from the Iranian Yauna, is a possible reference originally to the Ionian Greeks. Later the label Yavana was applied to those that came from the western direction. A distinction is made between Amtiyoko or Antiochus of Syria who is said to be close by, and the other four who are his further neighbours — Turamayo or Ptolemy (Philadelphus II) of Egypt, Amtekine or Antigonus, Maka or Magas of Cyrene, and Alikashudala or Alexander of Corinth. This stretch of West Asia and the eastern Mediterranean was not unfamiliar to Mauryan India.

Whether Ashoka had individual connections with each, or those farther away were known through kinship links, is hard to establish, but these kings were close kinsmen to one another. Ashoka’s closest connection was with Antiochus I, the son of Seleucus Nicator, and therefore the neighbour next door in Iran. The other four are mentioned as neighbours of Antiochus or those who live beyond. The officers propagating dhamma appear to have been sent to each of these kings.

The kinship links among the five Yona rajas was close. The Seleucid king Antiochus I had a stepsister who was married to Antigonus of Macedonia, the Amtekine of the inscriptions. His daughter-in-law was the daughter of Ptolemy II of Egypt. So the Seleucids, Antigonus and the Ptolemies were what from the Indian perspective would be various categories of “sambandhis” – families related by marriage. Antiochus also had a sister-in-law from Cyrene and a brother-in-law from Corinth, both kingdoms of the eastern Mediterranean. His widowed daughter-in-law had remarried, and her husband was Alexander of Corinth, who was the nephew of Antigonus of Macedonia. Ptolemy II, contemporary with Ashoka, had a son who was married to the daughter of Magas of Cyrene. In the next generation, a princess from the Ptolemaic royal family was married to the Seleucid king, Antiochus II. Did Ashoka have diplomatic relations with each of these kingdoms or only with the major ones, namely the Seleucids and the Ptolemies? The others may have been appended to the inscription, since they were closely connected, especially to the Seleucids.

Ashoka refers to his officers working among the people of the aparanta, the lands to the west along the Indus. He claims that as a result the dhamma is familiar to people who are located even six hundred yojanas – possibly fifteen hundred miles, or a substantial distance – beyond the frontier. Interestingly the imperial territories are more often identified by the people living there, rather than by geographical names. This was a familiar usage in ancient times.

Almost as a contrast, those listed from south India are not kings. They are the Cola, Pandiyas, Satiyaputto and Keralaputto, inhabiting the area as far as the frontier of Tambapanni, probably Sri Lanka. They are mentioned in the plural, and two carry the suffix putto – literally, sons – suggesting a reference to clans. They occupy the areas that adjoin the region of Karnataka where many Ashokan inscriptions have been found, and others inhabit what was left of the south outside the imperial domain.

Two important historical developments coincide with this. Sophisticated megalithic cultures are increasingly found in this area. These are different in form and organisation from the cultures of the Ganges plain and north-west India. They are also different from the Greek and Iranian cultures. These were, more likely, clan-based societies and not kingdoms. If so, it may have been thought unnecessary to conquer them and bring them under direct Mauryan administration. Was this perhaps a reason for not campaigning in the far south? Their political and economic potential may not have been compelling.

The second change was that the Brahmi script was being adapted to the Tamil language. This was the reverse of what had happened in the north-west where the same Prakrit language was being written in the localised Kharoshthi script. Large numbers of what have been called Tamil-Brahmi inscriptions have been found in south India and at ports along the Red Sea. Many are short votive inscriptions carrying Tamil names. A few Prakrit names in the Brahmi script also turn up as graffiti on potsherds at megalithic sites. Was the adaptation of Brahmi to Tamil suggested by the proximity of the Mauryan Prakrit inscriptions in parts of Karnataka?

The far south was as yet unfamiliar. The scene in north-western India was entirely different, hosting as it did both hostile armies and amicable merchants in territory and cultures that were by now familiar to all. The north-western borderlands had become like the back-yard of the Hellenistic, Iranian and Indian rulers.

The Seleucids succumbed to attacks from the Parthians from Central Asia who ruled briefly until the early centuries AD, when they too succumbed to the Sasanians rising as a power in Iran. The Sasanians were overturned in the late first millennium, partly by the Huns, called Hunas in Sanskrit sources, also from Central Asia. This was the hub of considerable activity that left its mark on Indian and Iranian history.

This brings me to the second major inscription on the pillar – the prashasti/eulogy on the Gupta king Samudragupta, composed and engraved posthumously.

The Ashokan edicts were more like conversational pieces addressed mainly to his officers and subjects, and largely concerned with how dhamma was to be propagated as a social ethic. The Samudragupta prashasti was entirely different, being a record of the king’s conquests and diplomacy. It was composed by a court poet, Harishena, and is dated to the mid-fourth century AD. So it was engraved on Ashoka’s pillar some six centuries after the Edicts.

Why did the Guptas choose this pillar? It was an artefact from the past that had no ostensible religious or social value. Whether the Guptas could read the Ashokan inscriptions remains uncertain. Probably not, else surely there would have been some comment on material so different from the Gupta record. The Gupta inscription endorses all that was contrary to what was said in the Edicts, as it glorifies conquest through violence. Dharma for the Guptas was the Brahmanical Dharma. They had no idea who the author of the earlier inscriptions was, but presumably the pillar appeared an impressive object. A lion capital would have given it an added royal significance. Was it an attempt by the Guptas, who were of a non-kshatriya caste, to claim the legitimacy to rule by inscribing their deeds on the pillar? In their other inscriptions, much was made of their marital alliance with the high status Licchavis.

This inscription begins with a passing reference to the pillar, described as being like the arm of the earth, and it goes on to proclaim the fame of the conquests of Samudragupta, who is no longer alive. The eulogy to the king follows. Nothing further is said about the pillar. The absence of comment on why it was chosen is puzzling. After all, it was no mere piece of polished sandstone but was deemed appropriate for the most important record of Samudragupta’s activities.

After the usual compliments to the king, the inscription lists his conquests and the frontier peoples whom he saw as important. In the initial list, a number of places (and their kings) in south India are mentioned, such as Kerala, Erandapalla, Kanchi, Vengi, and other kings of dakshinapatha or south India. They are no longer clan-based societies but kingdoms. This list points to Samudragupta campaigning via eastern India into the south and then across to Kerala. The conquests are said to be part of his violent extermination of the rajas of aryavarta and of the forests – atavika rajas. This distinction between aryavarta and daksinapatha is interesting, coinciding as it does with other texts that also make the distinction, such as the Manu Dharmashastra. Here aryavarta lies between the Himalaya and the Vindhya and between the two seas. Was this merely a convenient geographical definition or was the south seen as somehow distinct, although obviously less so than in Mauryan times? But since the Guptas never held the south, this march of triumph may have been, at best, a passing event.

We then come to the kings at the frontiers – pratiyanta nripati – and these begin not with the north-west but with the eastern and northern regions, such as Samatata, Davaka, Kamarupa, Nepala and Kartipura. The eastern frontier is now distinctly more in focus than in earlier times. On the western side, the frontier seems to be marked by the clan-based societies at the western end of the Ganges plain, such as the Malavas, Arjunayanas, Yaudheyas and Abhiras. This list of frontier regions would suggest a somewhat smaller kingdom than is generally presumed when mention is made of the Gupta Empire.

However, people further afield on the west and the south are mentioned.

There is a sense perhaps of a more alien world beyond what are described as the frontier regions. Nevertheless, it is said that Samudragupta, through vigorous self-assertion, bound together the whole world. He is assumed to be superior since the people of these faraway places brought him gifts and tribute, and some made marriage alliances. These included the Daivaputras, Shahs, Shahanushahis, Shakas and Murundas of the north-west. Then there is a geographical leap to the people of Simhala in the south and of all the islands. The geographical locations are not precise, since they are, largely, titles of rulers and ethnic names. A differentiation is being made between the frontier regions that he actually annexed, and those beyond that were perhaps merely part of diplomatic conversations.

The peoples of the north-west frontier, although not proximate, were not too far beyond. Here there is a degree of continuity from the earlier Mauryan period. In the intervening centuries there had been much activity on this frontier. But the activity was in relation to conquests and migrations from the Oxus plain and Central Asia. Among those who made their presence felt were the Bactrian Greeks, the Kushanas and the Shakas. They are referred to, some directly and some indirectly, in the inscription. A Kushana title gave rise to the term Daivaputra, and the Kushanas had earlier reached as far as central India. Shahi and Shahanushahi were titles taken by the Sasanian royal family when appointed as governors of Bactria north of Iran. Shaka groups ruled in parts of the north-west and in Punjab. The term Murunda was sometimes a title taken by Kushana and Shaka satraps. These were the groups that were attacked by the Hunas. This geographical shift points to Gupta diplomacy having to be aware of the threat from the Hunas, a threat that turned into violent confrontations with Samudragupta’s successors.

There is a small counter-part to this inscription that I shall mention just in passing. Samudragupta did issue a gold commemorative coin called the ashvamedha coin. This refers to the ancient horse sacrifice of Vedic times, when a horse was let loose and the raja who was the patron of the ritual claimed all the land across which the horse wandered. The attendants of the horse doubtless kept it to the straight and narrow. Those rajas who claimed to be conquerors indulged in this ritual. [siddham / ashvamedha-parakramah / rajadhiraja-prithvimave]. The performance of an ashvamedha sacrifice in post-Vedic times was a claim to conquest and status and indirectly a challenge to those that might have wanted to question it.

Gupta dinar, Samudragupta, Gold, About AD 335-80, Central India, Diameter 2.2 cm, Allahabad Museum

Gupta dinar, Samudragupta, Gold, About AD 335-80, Central India, Diameter 2.2 cm, Allahabad Museum

The statements in the inscription introduce new views of the world and new relationships. Of the various frontiers, the south now hosts familiar kingships close to the royal domain. Samtata, located in south-east Bengal, may have been a recent conquest and, by the time of the later Guptas, it is no longer on the frontier but an integral part of the Gupta domain. Its importance in this period points to the growth of trade between eastern India and south-east Asia.

This implied a turn to a new direction. In Mauryan times, attention had been riveted on places to the west of the sub-continent. Gupta campaigns seem to suggest an ambition to control the eastward-moving trade across the Bay of Bengal. The reference to Simhala / Sri Lanka, and the islands beyond, is intriguing. The names are not mentioned; but could it point to initial eastward movements to the islands of South-East Asia? Interestingly, this is where the Indian presence gets well-established in the post-Gupta period.

There was, therefore, a shift from contact with west Asia alone as in the Mauryan period, to far greater attention to Central Asia, and an initial interest in south-east Asia. The smaller polities and forest rulers of aryavarta are said to have been violently exterminated. Was this because they offered no resistance to the threat of the Hunas, or because they did not conform to kingship as the acceptable political pattern. It was also a response to another diplomatic tangle: the Sasanians in Iran, extending their power to the west, were coming into conflict with the Romans in the eastern Mediterranean and, later, in the north-east with the Kushanas and the Hunas from Central Asia. The Guptas were aware of the implicit aggression in this triangular situation. Hence the reference to their bringing tribute to Samudragupta, and his binding the world together through his prowess. The eulogy to him is a subtle play on Gupta diplomacy.

Let me turn now to the last of the major inscriptions, that of the Mughal emperor Jahangir. It is not as long as the earlier two, is composed in Persian and written in a fine nastaliq script by the emperor’s favourite calligrapher, Abdullah Mushkin Qalam.

Remarkably, all three inscriptions are engraved with great expertise by excellent calligraphers. The inscription records the ancestry of Jahangir. It is almost as if the pillar by now was recognised as bestowing legitimacy on rulers. It was thought fitting to have it inscribed yet again, although, like the eulogy on Samudragupta, the inscription arrogantly cuts into the Ashokan one, making it clear that the earlier ones could no longer be read.

We should not forget that in the fourteenth century the one remarkable conserver of the Ashokan pillars was Sultan Firuz Shah Tughlaq of Delhi, who shifted some of the pillars from obscure places to secure sites. This underlined their significance, even if the inscriptions remained unread. Jahangir had enough sensitivity to recognize that it was no ordinary pillar and carried a well-recognised aura of authority.

As a ruler, Jahangir was aware of the many directions in which his diplomacy was required. Perhaps more than any other Mughal emperor, he took his imperial name seriously, and wished to project himself as a world conqueror, a claim made by his ancestor Timur. A similar title had wafted over the Samudragupta inscription. The ancestry of Jahangir stretched from Central Asia to Rajput India. What then made him decide to have his genealogy engraved on the Ashokan pillar? Did he see it as a palimpsest, encapsulating historical consciousness? Did Jahangir recognise it as betokening his past as well, and more so given his Rajput kinship connections ? Was the gesture intended to reinforce the Mughal claim to the Indian throne? Engraving his presence on the pillar was a way of stating, almost sub-consciously, that he, like the others before him, was a part of this historical tradition.

Jahangir’s gaze on the world around him took him to the borderlands with Persia and Central Asia. The hub of the overland Asian trade was Afghanistan that many wished to annex. Some of the miniature paintings that he commissioned capture his gaze. I shall refer to three by way of example. The persons that symbolise the distant world are different in each painting. In two, Jahangir is depicted standing on the globe in a fantasy of wish fulfilment.

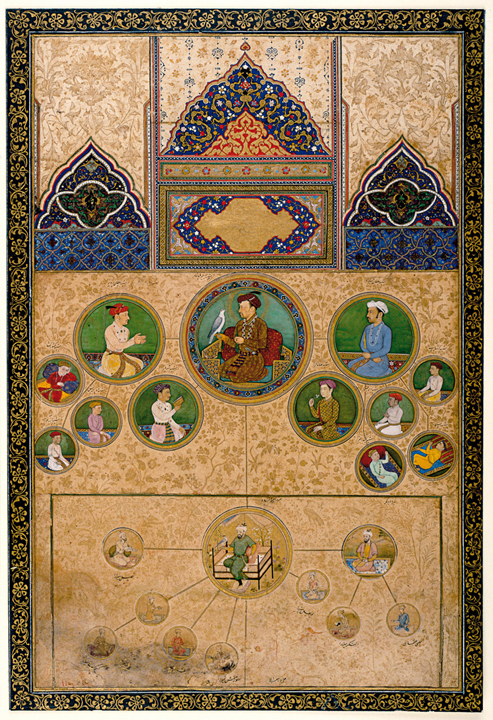

The counterpart to the inscription on the pillar is a painting consisting of portraits of his ancestors, painted as medallions. Jahangir remains the central figure with his male kinsmen surrounding him.

Jahangir — Pictorial Genealogy

Jahangir — Pictorial Genealogy

The Mongol ancestry was on the male side and therefore important, while his Rajput connections were on the maternal side. Timur was certainly better known in the world of his times than any of Jahangir’s Rajput forebears. The obsession with his ancestry may also have been a nurturing of Central Asian ambitions.

Jahangir’s territorial ambitions within India were somewhat thwarted by the irritating opposition of Malik Ambar.

A portrait of an African Nobleman (possibly of Malik Ambar), Gouache and gold on paper, About AD 1605-10, Ahmadnagar, Deccan, India, Height 20.5 cm, Width 10 cm, National Museum, Delhi (50.14/8)

A portrait of an African Nobleman (possibly of Malik Ambar), Gouache and gold on paper, About AD 1605-10, Ahmadnagar, Deccan, India, Height 20.5 cm, Width 10 cm, National Museum, Delhi (50.14/8)

A painting shows Jahangir facing to his right, and shooting an arrow at the head of Malik Ambar, impaled on a spear.

‘Jahangir shoots Malik Ambar’, Folio from the Minto Album, Painting by Abu’l Hasan, ca. 1616, Ink, opaque watercolour and gold on paper, H. 10 3/16 (25.8 cm) W. 6 1/2 in. (16.5 cm)

‘Jahangir shoots Malik Ambar’, Folio from the Minto Album, Painting by Abu’l Hasan, ca. 1616, Ink, opaque watercolour and gold on paper, H. 10 3/16 (25.8 cm) W. 6 1/2 in. (16.5 cm)

Such an incident never took place; but Malik Ambar was a serious enemy who had prevented the Mughal annexation of the Deccan. Malik Ambar has no turban and instead has an owl on his head – a bird of ill omen according to some. Jahangir stands on a globe placed on the back of a bovine animal that stands on an extraordinarily large fish. Was this a reference to Puranic cosmology where the fish was the Matsya incarnation of Vishnu that saved the world from the deluge? And was the bovine, the bull Dharma, who dropped a leg in each yuga to indicate the decline in Dharma? Two cherubs in the air above the king hold weapons.

Malik Ambar was born Ethiopian and sold into slavery a few times. When he finally arrived in western India, he was employed in the kingdom of Ahmednagar, where he worked his way up as an administrator until he was all-powerful. His administration was much admired. He organised guerrilla warfare against the Mughal armies, a strategy later used by the Marathas. Jahangir did not kill Malik Ambar, although he may have wished to, and the painting was apocryphal.

Apart from obstructing his southern conquest, Jahangir doubtless saw in him the presence of the East African South-Arabian migrants settling along the west coast of India becoming rich on the trade across the Arabian Sea. The two seas flanking the Indian peninsula had already become hubs in the commerce of the Indian Ocean. The arc of the Arabian Sea from the eastern coast of Africa to the southern coast of India hosted major maritime activities. It was being linked to Europe via the Cape, with the Portuguese initiating the link, but there was little awareness of the consequences. The Mughals were unconcerned with South-East Asia, now a separate segment of the Indian Ocean trade, monopolised by Arab and Chinese traders. The Mughals were looking beyond Iran and further west, a gaze that is hinted at in another painting.

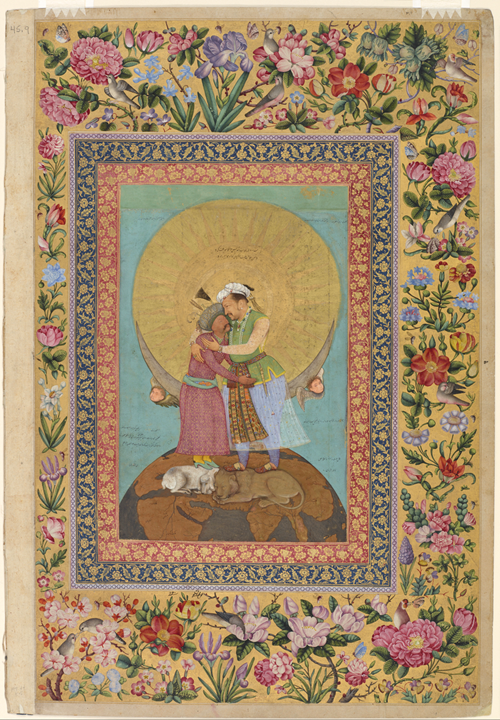

This painting, touching on Jahangir’s view of the world, was of the same period, c. 1618, and was equally apocryphal. It depicts Jahangir embracing Shah Abbas, the Safavid emperor. That the two ever met is doubted.

‘Jahangir Embracing Shah Abbas’, From the St. Petersberg album signed by Abu’l Hasan (act.1600-30), India, Mughal dynasty, ca. 1618, Margins by Muhammad Sadiq, Iran, dated AH 1170/ 1756-57 CE, Opaque watercolour, ink, silver, and gold on paper, Freer Gallery of Art, F 1945.9

Shah Abbas is shown as somewhat smaller in size, which is not surprising. He has almost a supplicant’s expression on his face, which doubtless was the way Jahangir wanted it. Jahangir was again depicted as standing on a globe of the world that shows a European seventeenth century map of the hinterlands of the Arabian Sea. Is this example of European cartography a pointer to the European world positioned on the threshold of Asia? Although Jahangir is depicted standing on the junction of three Asian empires, the fantasy proved to be short-lived. The nimbus that captures both rulers is so large that it forms the background to both their torsos. Significantly, Jahangir has a lion at his feet whereas Shah Abbas has a lamb, symptomatic, no doubt, of how the Mughal saw his relations with the Safavid king. Was this a form of diplomacy?

What I have tried to show is that this Ashokan pillar, together with its inscriptions, is a remarkable historical object, encapsulating history in many ways not immediately apparent. There are many pillars in India that carry the occasional inscription. But the Allahabad Pillar of Ashoka is remarkable for the particular inscriptions it carries, and the altogether different statements that the inscriptions capture, with their wide-ranging implications. These are a reflection of diverse periods of Indian history, extending across three millennia, with each later inscription registering change. The pillar remains an object that informs us of how India looked at the world at various times. Perhaps if one were to delve deeper, it may be seen to reflect, albeit indirectly, the world’s view of India. It does not tell us why it came to be the site for a few of the most meaningful statements of Indian history. Yet it continues to be an object that has the power to generate history and demonstrate that history never actually comes to closure. The perpetual search for its meaning keeps us continually writing history.