The Heart Fixes on Nothing

Zafar

The heart fixes on nothing in this wasted province.

Whoever made anything of a kingdom of shadows?

Go find another home, my smothered hopes.

This stained heart has no roof to offer you.

I prayed for long life and got four days:

two were spent in desire, two in waiting.

Gardener, don’t rip these thorns from the garden:

they were raised with the roses by a gentle spring.

The nightingale doesn’t blame the gardener or the hunter:

Fate had decided spring would be its cage.

Fate’s real dupe: that would be you, Zafar, your body denied

two yards of spaded earth in the Loved One’s country.

And Sometimes Rivers

And sometimes rivers

that run in your veins

change course.

Silt marks the spot

from where you set sail

to circumnavigate the globe

and where someone wearing your sunburned face

stopped thrashing about in mangroves that wouldn’t let go

and stood still, bleached hair ruffled by the wind,

as if, after a voyage charted across fevers and hurricanes,

riding at anchor.

The Oracle Tree

The woman walked up to the oracle tree

and bled its bark for answers.

It’s no use trying, said the tree.

They’ve tied me up with holy threads.

Roots burn through my shoes,

leaves cloud my eyes.

I’m not me. I’m

that man jogging along the promenade,

arms outspread,

scattering fistfuls of feathers

to the winds.

Ranjit Hoskote speaks to Souradeep Roy about Jonahwhale

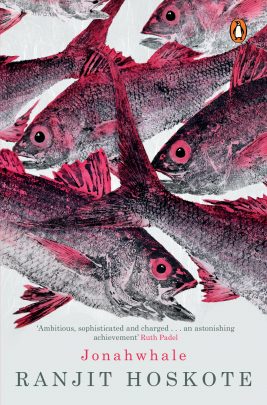

Cover image of Jonahwhale / Image courtesy Penguin

Cover image of Jonahwhale / Image courtesy Penguin

Souradeep Roy (SR): You have had a fascination with water and not land, and the specific kinds of movements that water allows. Thematically, I could link your book with Jussawalla’s first book of poems, Land’s End. But you seem to stretch the metaphor further and begin from the sea itself. How much has the sea affected your life, and since when have you thought of it as material for writing?

Ranjit Hoskote (RH): I have long been fascinated by geographical and cultural mobility across land as well as water — the manner in which people over the centuries have created webs of interrelatedness across natural boundaries and in defiance of territorial borders. As a poet, as well as a student of cultural history, I warm to the way in which pilgrims and merchants, scholars and artisans, soldiers and monks, storytellers and sailors have met in shifting contact zones and created new continents of affinity, rather than remaining programmed by the limitations of local circumstances.

Of course, you’re right about how water allows for particularly dramatic transcultural journeys — epic migrations, long arcs of travel that carry people, goods, ideas, beliefs, narratives, and art forms from one place to another in the most unexpected ways. I think of how India’s maritime adventures drew countries as far away as Indonesia and Cambodia into what Sheldon Pollock has memorably called the ‘Sanskrit cosmopolis’, so that a grammarian in Taxila, a dramatist in Ujjain, and a theologian in Borobudur would understand one another readily. I think of the Islamic ecumene, which created a global circulation that brought Javanese, Uzbeks, Maghrebis, Sudanese, and Albanians together into a community that balanced off doctrinal conformity with imaginative diversity.

In the process, to name but one example, the Shuka-saptati, the ‘Seventy Tales of the Parrot’, travels into Persian and becomes the Tuti Nama and into Javanese to reappear as the Hikayat Bayan Budiman. Between the 17th and the 19th centuries, the shipping routes of the world’s colonial empires threw diverse crews together — Konkani, Bihari, Tamil, Malay — and from their interactions emerged new languages, such as Lashkari.

Jonahwhale operates as an interplay between solitary maritime heroes whose presence is stated or implied — Jonah, Sinbad, Ahab, Nemo, Odysseus — and the collective, literally motley crews who are largely anonymous, yet without whom the so-called Age of Exploration could not have taken place.

‘Three Lascars on the Viceroy of India’ (Marine Photo Service, 1929). Coll. National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London

‘Three Lascars on the Viceroy of India’ (Marine Photo Service, 1929). Coll. National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London

+

I was born and grew up by the sea — in Bombay and Goa. The sea has always made its insistent presence felt in my life, consciousness, and writing. Standing on the shore fills me with a tremendous sense of being at the edge of a seemingly infinite expanse, a reminder of how modest and ephemeral our species is, in the context and against the scale of the planet we’re busy destroying with our insatiable desire to exploit, control, consume, and eventually self-destruct.

+

It’s very kind of you to suggest Adil Jussawalla’s pathbreaking Land’s End as a point of reference, but I should clarify that Anglophone poetry in India is not the only framework by which I navigate. My practice, as a reader and a writer, is varied, and not confined to a single literary tradition or a single language — to adapt a turn of phrase from Hindustani classical music, I am a post-gharana poet!

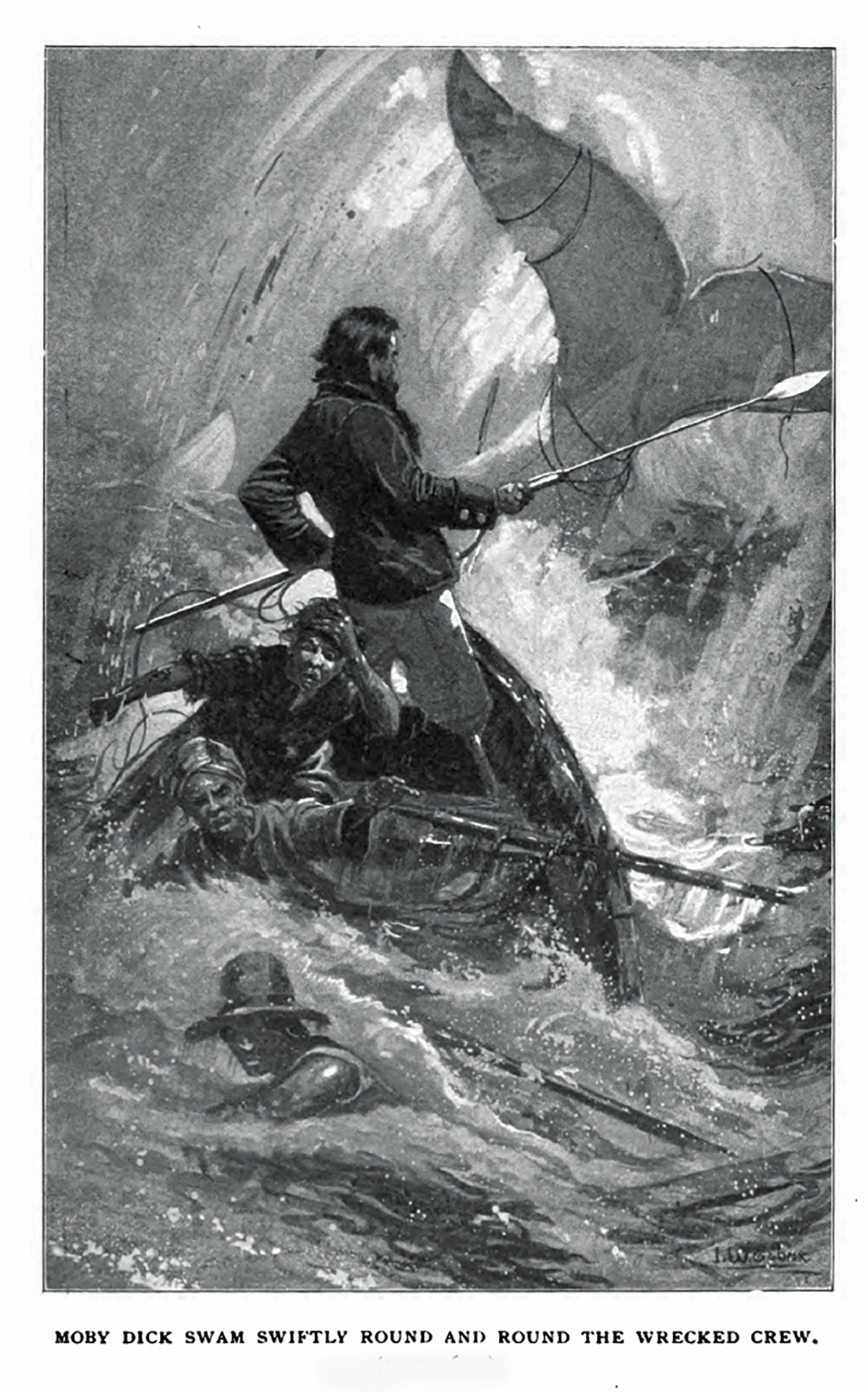

My starting points for Jonahwhale are quite diverse, and come from the pluriverse that I inhabit as a writer and reader across languages, cultures, and periods – they embody my long-term engagement with several writers, books, and their atmospheres. Among these are Melville’s Moby-Dick, of course, and — equally crucially — the French poet-diplomat St John Perse’s book-length poem, Anabase, translated by T S Eliot in 1930 as Anabasis; as well as the Martiniquais philosopher Edouard Glissant’s Poetics of Relation; and the French poet René Char’s La parole en archipel.

‘The Final Chase of Moby-Dick’, illustration by Isaiah West Taber, from Herman Melville, Moby-Dick (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1902)

‘The Final Chase of Moby-Dick’, illustration by Isaiah West Taber, from Herman Melville, Moby-Dick (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1902)

Other points of departure for Jonahwhale include sources and exemplars from outside the domain of poetry — I have been nourished, while working on this book, by pre- and non-Columbian atlases and charts, such as those of al-Idrissi, Piri Reis, and Zheng He, cartographers and navigators in whose work I have long been immersed.

Piri Reis, ‘Map of the Nile Estuary, with the Cities of Rashid and Burullus on Each Side’, from the Kitab-i Bahriye (1521-25). Coll. Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, MD

SR: ‘my name is Ocean’ — the dramatic monologue of the ocean begins with this line. Does the personal pronoun ‘my’ also stand for your own self?

RH: That line announced itself to me, one day in February 2014, as I was crossing the Sea Link — the curved bridge that takes you out of Bombay and over the bay for seven minutes, if you’re lucky with the traffic, and back — and looking down at the tide. Only after the poem had come together did I register why that opening line resonated so strongly for me. It carries, in fact, a Biblical ring — from the episode in the Synoptic Gospels when Jesus exorcises a man in the city of Gadara, driving the demons that have possessed him into a herd of swine, which then hurl themselves over a cliff. When Jesus asks the demons their name, a standard move in exorcism, they answer: ‘My name is Legion, for we are many.’ (Mark 5:9)

On a visit to Jordan in January 2009, I stopped at the city of Umm Qais — the Gadara of Roman times. With its Caesarean ruins and panoramic vistas of the Sea of Galilee, Umm Qais formed a dramatic, plausible setting for the story. We looked down the slope where the Gadarene swine are believed to have leaped into the void.

The suggestion of the transgressive manyness of Ocean, who is the main speaker in the poem, soon fulfills itself: the location of the voice shifts several times, and without warning, from Ocean to the chroniclers who follow in the wake of tidal catastrophe. In turn, the chroniclers reference languages that are endangered, near-extinct, or threatened by aggressive neighbouring languages: they invoke the speakers of these languages, about to be silenced. Capitalisation and punctuation break down, as though swept away by the waves; indents and other spaces open up. The poem ends with Ocean reciting every narrative he knows, from his depths — he is, after all, the katha-sarita-sagara of Somadeva, the ‘ocean of the rivers of stories’.

+

Is the ‘my’ in the opening line of ‘Ocean’ a reference to my personal self? It is very difficult to stabilise and confine the personal pronoun ‘my’ to a single, sovereign self today. Consider our predicament — we are defined by our interdependence on others. What is it to be or have ‘one’s own self’ today, when our selfhood is distributed across diverse physical locations and affective investments, delegated to our electronic prostheses and digital avatars, and intertwined with the selfhood of others? Crises link our fates to those of people we have never met, but with whom we share cartographies of schism, tremor, and dislocation across the planet. In these circumstances, I gear myself — my self — to the condition of dividuality rather than a classical, irreducible individuality, the recognition that ‘we are many’, that our subjectivity is a kaleidoscope of rival, contending, coincident selves.

And where do we draw the taxonomic lines separating one species from another, even as we acknowledge that homo sapiens — named in a spirit of optimism rather than accuracy — is the only species that systematically destroys its habitat? The Jonahwhale of my title, apart from carrying mythic resonances from the Old Testament narrative of Jonah, is also a reminder that whales are mammals, not fish — that they once inhabited dry land. In his brilliant study of India’s deep ecological history, Indica, Pranay Lal speaks of the whale cemeteries that stretch from Jammu to Kutch — the fossil remains of as many as 18 species of ancestral whales are found in this region, which was once the Tethys Sea. What seems like land was once ocean; what is ocean today could once again be land. Our destinies are bound up with those of seemingly distant species, who turn out to be closer to us than we realised.

SR: I am interested in the range of styles you use in this collection, from a one-line poem (‘Planetarium’) to long poems that steer towards an epic narration. Do you too consider yourself to be a poly-stylist?

RH: Since I often approach questions of poetry from a musical or architectural perspective, I focus less on style, and more on formal, even artisanal, choices. I am not interested in producing a single kind of poem — rather, I am invested in crafting poems of several kinds, each kind addressing specific questions of poetics, of voicing, of tonality, and which stretch the language in different ways.

Yes, as you suggest, the book is structured along a play of scale, from the intimate to the epic — from the monostich or single-line poem to long poems that riff on the choric and the polyphonic. A poem like ‘Cargo and Ballast’ is written like a libretto for opera, with a variety of voices, some singular, others an ensemble, with a continuous variation from aria to recitative. ‘Cargo and Ballast’, ‘Redburn’, and ‘Baldachin’ are intended to act as musical scores, to be interpreted by various voices, set to varied tempi.

Jonahwhale attests to my lifelong devotion to music — here, particularly, that great 20th century tradition of avant-garde experimental music, sometimes misleadingly described as ‘minimalist’, which includes distinctive exponents like Steve Reich, Terry Riley, and Brian Eno. Reich’s percussive, still-amazing 1965 work, ‘It’s Gonna Rain’, informs ‘Baldachin’.

Steve Reich, ‘It’s Gonna Rain’ (magnetic tape with phase shift, 17 min 50 sec, 1965). Screen grab from Youtube

‘A Constantly Unfinished Instrument’ is dedicated to Eno. The spirit of Riley’s music appears in various poems. And ‘Cargo and Ballast’, of course, is punctuated with the bandish lines from some of our loveliest thumris, chaitis, and kajris, resonant with the voices of Siddheshwari Devi, Begum Akhtar, and Girija Devi. And yet, those musical compositions, composed by women, encode political and juridical violence, the memory of loved ones dragooned into the army, forced to migrate to the city for work, or taken away to serve as indentured labour in the South Pacific or the Caribbean. Sainya ko le gaye thanedar, goes one. Ab ke saavan ghar aa ja, goes another.

+

Some of the key poems in Jonahwhale unfold as projects in mapping an ars poetica — ‘Baldachin’, which I seem to be talking about extensively, wrestles with the project of shaping a Romantic approach that can take on the urgencies of the early 21st century, its toughness tempered with sensuous regard, its love of gorgeousness veined with sense, its taste for catastrophe held in counterpoint by a feeling for splendour. This is, as is evident, a wager on the Sublime — with all its capacity for terror and bewilderment.

‘The Poet’s Life’, the poem that closes the volume, delineates an ars poetica too — it spells out a pattern of quixotic observation and eccentric commitments, oblique entries and exits, an embrace of collegiality and collaboration alternating with solitary retreat, and the refinement of two aesthetics, one pagan, festive and life-affirming (‘He painted their grey nets in grainy gold on the beach.’), the other premised on shibui, an awareness of the evanescence and ephemerality of all things (‘He collected the rust and shadows that gather on ageing metal surfaces.’)

Building on the archipelagic thought of Glissant and Char, the third section or movement, ‘Archipelago’, sets up a chain or garland of discrete experiences and moments, which build into an assemblage, defined as much by its interrelationships and cross-references as by the individuality of its components.

SR: I am interested in your use of Notes at the end of the book, mostly because it is not quite common among Indian English poetry collections (I am not considering translations here). A collection that uses so many allusions is also rare. I tend to think that the use of several voices in one poem or collection has few precedents, like, maybe, Adil Jussawalla’s Missing Person, which was a text that confused several readers. Did these anxieties ever come to you in your choice of using the Notes? What prompted you to incorporate such a section?

RH: Pleasure, not anxiety, is the ground from which the Notes in Jonahwhale arose. I am no stranger to allusions — my books have always been replete with them. Had I been anxious about this, every one of my books would have come accompanied by a section of Notes!

In Jonahwhale, which marks the breaking-down of so many previously self-enforced divisions — between my love of the classical impulse in poetry and of disruptive avant-garde strategies in the visual arts; between an Anglophone register and the presence of other languages, such as Awadhi, Brajbhasha, Konkani — I thought I would also dissolve the line separating my too-often held-apart lives as poet and as scholar. Adding another dimension to the hybridity of the book’s form, I did away with the distinction between a volume of poems and a scholarly work. To me, it’s about the rustle of different registers of language!

As it happens, I enjoy annotation for its own sake, for the pleasures of reverie and rambling, the opening up of half-glimpsed connections, the establishing of genealogies of events, and calibrating historical horizons. I’ve practised this already in two previous books: I, Lalla: The Poems of Lal Ded, my translation of the 14th century Kashmiri saint-poet’s work, which is accompanied by detailed notes to the poems, and Dom Moraes: Selected Poems, my annotated edition of Dom’s work, which treats the notes to the poems as an extended meditation on his sources, contexts, choices, dilemmas, and his evolving trajectory. As far as the art of annotation is concerned, I have been inspired by two great, marvellous, sometimes delightfully whimsical practitioners: Richard Burton and Ananda K. Coomaraswamy.

SR: This is, no doubt, a major, grand book that you have written. There is an ambition here that is rare in contemporary writing, especially in the Indian English tradition. Do you consider this to be your magnum opus, as far as your previous collections are concerned?

RH: Thank you so much: this is very kind of you. Of course, it is not for me to say whether this is my magnum opus. It is my friend and colleague, James Byrne, who has very kindly described Jonahwhale as such.

My project in Jonahwhale is, bluntly put, to break open the lyric. I have no patience with the reflective, sometimes confessional lyric premised on the narrowly personal ‘I’, its complaints and afflictions and role-playing. This gets especially irksome when, under the banner of ‘the personal is the political’, the stringently political gets reduced to the self-indulgently personal. My concern in Jonahwhale is to operate with a larger ‘I’ that is sometimes ‘we’, sometimes ‘them’, sometimes ‘us/ them’ — which accommodates, welcomes, yet is also perturbed by multitudes; which is schismatic, farouche, numinous, and palpable. The formerly invisible subaltern figures of the global maritime history of the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries come to view, and to audibility. The refugee and the survivor are invoked. They do not remain outside the ‘I’, objectified or exoticised. To me, these strategies pertain as much to poetics as to politics.

In the Introduction to her recent book of essays, The Ocean, The Bird, and the Scholar: Essays on Poets and Poetry (2015: 3), the critic Helen Vendler writes of the ‘fundamentally different structures of literature — linear in narrative, dialectic in drama, and concentric in lyric.’ While the magisterial Vendler’s point is a useful one, I remain unconvinced, as a writer, that one must forever retain these silo-like distinctions. In Jonahwhale, I wanted to experiment with mixing these modes, to merge and over-dub them.

+

In the Introduction to I, Lalla, I reflect on the passage of texts from orality to scribal culture to print modernity, and how each phase possesses its strengths and its disadvantages. Orality allows for the freedom of simultaneous versions being in play; print modernity imposes the dogmas of authenticity, originality, and a single authorised version. As a poet who works within print modernity, how might I retrieve and re-appropriate some of the latitude of oral culture? How might I unknot, dismantle, shake up the printed text? Mise-en-page is a vital aspect of the Jonahwhale project — it helps push the written and printed text in the direction of the mutable, mercurial, tricky voice.

In many of the Jonahwhale poems, the body of the poem is stretched, exploded to the edges of the page; the poem appears as a scatter pattern or diagram on the page. Sentences assume the form of temporary continua sometimes; and sometimes, all punctuation disappears, and a voice carries — or several voices carry — the text forward on the strength of cadence. The page opens up to indicate and accommodate layered utterances, silences and erasures, the word visible yet cancelled, voiced yet unvoiced, perhaps to be rendered sotto voce. Sometimes, as I say in the poem, ‘As It Emptieth Its Selfe’, with its use of entries from Macaulay’s diaries and from colonial-era hydrographic maps, we must own up to our speech as ‘stutterance’.

In this spirit, the poem ‘Redburn’ is a palimpsest. First of all, it takes an extract from Melville’s novel, Redburn, and subjects it to overwriting, erasure, editing, spatial transformation. It then invites readerly ingenuity as a text to be read – how do you speak a word, phrase, or line that has been crossed out on the page, yet retained under the cancellation? Likewise, ‘Philip Guston, in (Pretty Much) His Own Words’ is, pretty much, that — a meditative selection of phrases and passages from the great American artist’s talks, lectures and writings. I’ve collaged, edited and added interpolations to this purposively found material, to create a three-part constellation evoking three major venues of art-making, dialogue and criticism, especially in the expanded School of New York folklore: the lecture, the studio visit, and the loft.

And so, an avant-garde poetics is activated throughout Jonahwhale: the collage, the montage, the objet trouvé, the cut-up, looping, antiphony, all come into play as formative and integral devices in the making of poems. I’m preoccupied, in many of these poems, with questions of temporality: duration, simultaneity, counterpoint. I’ve turned back, during the writing of this book, to the maverick William S. Burroughs, who pioneered the cut-up and fold-in techniques, together with Brion Gysin, at an early moment in the history of the dialogue between poetics and emerging technology.

As Burroughs says to his interviewer, Daniel Odier, in The Job (1969: 29), it was ‘Brion Gysin who pointed out that the cut-up method could be carried much further on tape recorders. Of course you can do all sorts of things on tape recorders which can’t be done anywhere else — effects of simultaneity, echoes, speed-ups, slow-downs, playing three tracks at once, and so forth. There are all sorts of things you can do on a tape recorder that cannot possibly be indicated on a printed page.’ In Jonahwhale, I’m trying, modestly, to indicate just such effects.

+

Another point of departure for me, in Jonahwhale and in an ongoing project that I have, at the cusp of poetry and the visual arts (‘Letters to al-Mu’tasim’), is the muraqqa or album, prized by the Safavid, Mughal, Ottoman, and Adilshahi visual cultures. It was part portfolio, part scrapbook, part journal, containing original paintings, copies, prints, calligraphic annotation, and text, all bound together.

In ‘Cargo and Ballast’, different voices, extracts from judicial documents, maritime records, the phantom of a Turner painting, and pop-cultural references, all come together into a muraqqa that mourns the victims of the slave trade. Jonahwhale, too, is a muraqqa – it enfolds, within itself, my translation of a ghazal by Bahadur Shah Zafar in his Burmese exile (‘The Heart Fixes on Nothing’) as well as my super-compressed version of the Ramayana with the emphasis on Sita’s perspective (‘After the Story’).

J M W Turner, ‘Slavers Throwing Overboard the Dead and Dying – Typhon (sic) Coming On’ (1840). Coll. Tate Britain, London

J M W Turner, ‘Slavers Throwing Overboard the Dead and Dying – Typhon (sic) Coming On’ (1840). Coll. Tate Britain, London

SR: The section ‘Poona Traffic Shots’ seemed to resemble a kind of writing that is familiar to someone who might have been following Indian English poetry, especially in the use of narrative in terms of form; and the description of place, in terms of content (images like ‘the rainfall per square inch of skin’). You have written this from July 1991-July 2014. How did you revise, rework some of your earlier poems? Why did you wait for this book to publish these poems?

RH: ‘Poona Traffic Shots’ is actually one long poem in ten sections – but readers are welcome to read it as a section comprising ten poems. That works fine, too!

The dates are somewhat misleading. The poem was written, pretty much in its entirety, during a highly intense period of a week or so, during the monsoon of 1991. And then it sat in typescript, in a folder, for decades. Every few years, I would take it out, look at it, alter some punctuation, re-jig a phrase here or there. A strophe was added to one of its sections, at some point. When I finally decided it should go into a book, as a central axis to Jonahwhale — a pulling-back to land before putting out to sea again – I revised the closing section. This happens to me quite often. A poem may remain in one of my notebooks or folders for years before it goes into a published volume. It has to find its appropriate location and circumstances, its kairos!

‘Poona Traffic Shots’ is not, strictly speaking, a narrative. While the myth of the journey gives it a sense of linear progression, it’s actually an epic assemblage involving syncopations, disruptions, changes of scale and tempo. In 1991, when I wrote it, I was 22 and discovering the penumbra and incandescence of cinema — Tarkovsky, Parajanov, Mani Kaul, Kumar Shahani, Abbas Kiarostami, Mohsen Makhmalbaf. I was enchanted by the possibility of treating each section in the sequence as a shot, moving fluidly from tracking the protagonists, panning across vistas, taking a crane or a tilt shot in some situations, capturing camera shake. Several sections of the poem were written looking out of a bus window in the rain, going from Bombay to Poona and back.

A central theme of Jonahwhale is anamnesia — a refusal to yield to forgetting, a going over the contested terrain of memory. Re-reading ‘Poona Traffic Shots’, I note its references to the ascendancy of the military-industrial-academic-technocratic complex, the first Gulf War, the assassination of Rajiv Gandhi, the ballot-stuffing during local elections — I look back, and I look around me, and think of how certain historical continuities still ripple among us. ‘Poona Traffic Shots’ looks forward to the more compressed ‘Highway Prayer’, written in September 2016 on a bus ride from Ithaca to New York City, as a testament to our familiar yet estranging tropical politics of saviours and shysters, streetfighters and tele-buffoons, panic and apocalypse.