In that gentle winter night, as the full moon spread sweetness and light on the heartless ground near the Power House, the cold came down on the people like an unseen blind axe. It sliced mercilessly into every inch of their bodies. And so these beggarly, jobless people, who did not possess even the rudest hut, burnt with jealousy at the sight of each other’s blankets. Husbands and wives fought over the blanket covering them. Children cried for their mothers and fathers, and dogs whined to work up some warmth.

The cold hurtled over that ground like a herd of maddened elephants, crushing those people under their feet. But it affected David-dada, who was not poor and feeble like those people on the ground, differently. The cold was like a loving embrace. It brought back the life-force into his body that had been beaten into unconsciousness.

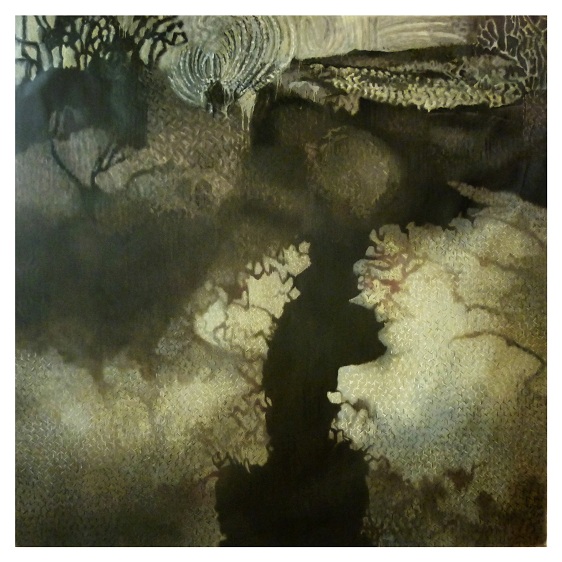

He lay, limbs akimbo, covered in blood, among the dense bushes under a tall black leafless coconut palm. His attackers had tossed his dagger near his body. David-dada lived by collecting money owed by the bootleggers, and the shopkeepers who supplied the bootleggers with raw materials. These people, tired of his unreasonable demands and beatings, had, with the consent of the police, thrashed him and left him for dead among the bushes. The cold wind slowly brought him back to consciousness. He got up. Stumbling, somehow bearing the pain, he managed to get to the trunk of the coconut palm. He could walk no further. He sat, leaning his broad strong back against the trunk and spreading his muscular legs on the rising ground. His blood-soaked tufts of hair, now stiff with dried blood, hung over his ears and on his fair, reddish forehead. His neck, not used to bending even after being thrashed, was straight. His ample chest, which somehow had room for humanity as well as inhumanity, withstood the whipping cold easily. His generous and proud hands held his dagger; even sitting there now, he had the arrogant bearing of a tiger. As water washes away sins, so the cold chased away his weariness and his lethargy; it was as if it saw his suffering and gave his godly or ungodly nature back to him.

Meanwhile, the cold pushed and jostled the other poor and feeble people on the ground. It made mincemeat out of young Abdul Kareem who had T.B. Jobless, trying to satisfy the desires of a starved youth, he had sold his blood to the blood bank. He spent the money on prostitutes and qawwali sessions and was fast becoming penniless. The cold danced a ghastly dance on his wasted body, and he shivered like a chicken with its head cut off. A pain rose in his toes and fingers, and his empty stomach. When his hands and feet went numb, he shouted and stamped his feet. He lifted his back from the ground so the cold would not settle on his back and chest again. Sometimes, he tried to dig into the ground under his back as if hiding under bed sheets. But the earth under his body did not open its arms to him, or hide him. It left him out in the open, and the cold chased him as if it was hungry for his life. Trying to get some warmth into his body, he rubbed himself raw, yelling, ‘Allah let me live… let me live… be merciful…’

But Allah didn’t listen to him or have mercy on him. And the people around him did not get up, lift him from the lap of death, draw him close to them. Becausethey too were worried sick by the cold. Near him, an old couple, Zunkaavu and Supad, were asleep under their dirty patchwork coverlet. Under their heads, and at their feet, was the saleable rubbish they had foraged from the dumping ground at Chembur — rags, paper, glass and tin — stuffed in bundles into gunny-sacks. They had only a filthy coverlet over them, and, like Abdul, the cold had driven them to a state past endurance.

They had spent their whole life together, but as the piercing cold made their bones ache, they squabbled and pulled at the covers. Driven out of his village, his job, and the chawl in Mumbai because of his fiery temper, trying to forget his sorrows by smoking gaanja, Supad hit his wife. Zunkaavu, who had suffered his blows all her life, was furious, but still she huddled close to him to keep out the cold. She was angry and bickering, clutching at the coverlet. She was telling him about all the injustice he had done to her, all his beatings; and he, cursing, hit out with his knees and elbows, pulling at the cover.

Sixteen-year-old Raamu had spread a sheet of tarred brown paper on the ground and he lay on it with a pile of old newspapers serving as a pillow, covered by a piece of sacking. On his chest was a gunny-bag full of paper, which he held tightly with both hands. During the last four or five years — since his parents died — he had made a living by picking paper up from the road and from dustbins. He too was shivering from the cold. Still, he held on to the load of paper on his chest. He was afraid some vagrant would burn his paper-earnings to save himself from the cold; so even though his fingers were stiff, he would not let go of the sack. He stayed awake in case somebody smashed a stone on his head to get at the sack. There was nobody nearby who might murder him; but in that harsh cold, he saw no good in anyone.

Beyond him, a giant south Indian leper slept with a ragged sheet covering him and a tiny puppy clasped to his side. The pup whined incessantly, trying to get out from under the sheet, while he kept fondling it. His body shook with the cold, while his mind was troubled by memories of his wife and her plump body. He was tortured by the thought of the pleasure he had enjoyed in her company for a good ten years. He wished he had a woman beside him now as he stroked the pup, sometimes with affection, and sometimes with anger at the thought that his wife was sleeping with someone else. He pressed it, and when the dog yelped, he comforted it. The memory of the flourishing domestic life he had left behind pained him; it made him restless.

A little distance from the leper, a mendicant couple lived on a downward slope where they had cleared a spot among the shrubs. Just two weeks ago, the woman’s husband had been arrested while they were begging on the road, but the police had let her go as she was pregnant. She had begged all day, eaten the food she had got by begging, and was sleeping in her usual place. Her stomach ached because of the cold. She didn’t know if the pain was because her labour had started or from the cold. She cried out from time to time. The troupe of Faase-Paardhis who were not too far away, ignored her, even though they heard her shrieks, because they too were being whipped by the cold. Their small children were crying, quarrelling over the blankets. Since it was forbidden to light a fire as the powerhouse was nearby, these people tried to warm themselves with all kinds of antics. Young couples without children hugged each other; some lay on top of each other, some made love, and the winds that blew against mankind tore away the drapes covering them and left them bare.

As for the young virgin Sona, who lay between her grandmother and grandfather, the cold had aroused a storm of desire in her heart. She shifted restlessly, and her movements annoyed the old couple who were already irritated by the cold. Both shouted at her to lie still. But the waves of longing that the cold had aroused in her would not let her be. They made her move her limbs restlessly. She moved her blanket off her face so that she could not avoid seeing the amorous play of the couples in her troupe. These people, hardly blessed with an abundance of clothing, had found a way to work up heat by rubbing their bodies together. Watching them put this solution to effect agitated young Sona’s mind, and she pulled the blanket off her face and stared at them like a madwoman, ignoring the cold and her grandparents’ scolding. Annoyed with the girl’s behaviour, her grandfather made her get up then hugged the old woman tightly, trying to warm his body. Sona sat shivering at their feet, her eyes darting from her embracing grandparents to the people of her troupe. Her grandfather, still trembling from the cold, commanded, ‘Don’t just sit there like that. Get behind me and hold me tightly.’ She clasped him, and he felt better with the contact of a young, warm body. He squeezed the old woman, and as the trembling of his muscles slowed down, he felt the stirrings of an enfeebled desire. So, he shouted for Sona to get up. As soon as she separated from him, the old woman asked her to sleep behind her. Then he and she, by turns, took shelter from the cold behind Sona’s young body, and the exercise made her even more agitated with desire. She moved away from her grandparents and lay with a thin sheet over her. Watching the amorous movements of her kinfolk nearby made her restive and she wished that there was a young man beside her, that he would rub his firm body against hers, that he would squeeze her. She lay some distance away from her grandparents, hoping that someone would come to her, but nobody came, because all the young men in her troupe were her paternal cousins.

Sharp waves of cold were assailing her now, and they stoked the fire of passionate hunger inside her. She sat up, clasping a cloth around her, looking at the fornicating couples among her kinfolk. Then she cast her body on the ground in shame. As the cold intensified, as did the scenes of naked lust around her, she lost her senses. She was ready to commit sin. She stood up, intending to get under someone’s blanket. She could see the giant leper from Madras muttering at a distance, Raamu sleeping at his side on a sack, and Abdul, shuddering with cold. As she stood there shivering, wondering which of the three she should go to, she saw someone gesturing and calling out to her. She looked at him intently. Seeing the thick blanket covering him, she took two steps towards him and stopped. The bitter cold had got into her every nerve and muscle. She came forward quickly and stood before the strange man who was on his feet with a blanket on his body. As soon as the young hot-blooded woman came to him, he stretched his arms, embraced her, and sat down with her. They disappeared together under the blanket.

Resting against the tall palm, David looked at the people with all their troubles. The sight of Abdul, chilled to the bone, tossing and turning, twisted up his insides. Hearing the screams of the pregnant beggar-woman lying among the bushes made his heart shudder. Listening to the painful tale that came to his ears from the quarrelling of the old couple Zunkaavu and Sukad, his generous hands yearned to help them; and the sight of Sona fornicating with a strange man because of the cold, numbed his brain. He was lost in thought, smoking cigarette after cigarette, when a clamour came to his ears from the Faase-Paardhis:

‘Where’s Sona? Where’s Sona?’

They roamed over the ground tearing the blankets off any couple they saw. As soon as they saw Sona, her chastity spilt, sleeping with a stranger, they began to beat both of them. Both the young and old of that troupe set to beating the man with any object that came to hand till he was covered with blood. He fell down, but they would not let him go. They were not a cruel people by nature, but they thrashed him without thought for his life because beating him brought warmth and a spark of life to their bodies.

And the sight of these beatings just for the fun of it, of the cruelty that had descended on these people with the cold, caused an explosion in David’s heart and he cried out in rage,

‘Eh, you Paardhis! Leave him alone! Will you let him go or not?’

Clenching the dagger in his hand, he leapt up from where he sat like a cheetah and ran towards the nomads. His furious voice and aggressive movement made the beaters-for-the-fun-of-it move away in alarm. At the sight of the dagger in his hand, they ran helter-skelter; the women and children cried and shouted as they tried to save themselves. Seeing them run away in fear, he turned back. His enraged gaze fell on the ailing Abdul Kareem, tossing and turning, begging for death to release him. David bent, pulled him up by his hair and asked,

‘Eh, who’re you?’

Frightened by David’s voice and the electrifying touch of his hand, Abdul said piteously, ‘I’m a poet, all my life I’ve loved women and poetry, and this is the way I am punished…’

‘What d’you mean?’

‘Don’t hit me. This heartless world of yours has killed me. If you hit me, send me straight to God. So that he won’t send me back into this world. Let me go.’

David loosened his grip. Abdul fell back on the ground. He was complaining at having been struck, speaking the name of God, sobbing. A volcano of anger and tears erupted in David’s heart. His generous hand went straight to his pocket, but there was nothing in there except a packet of cigarettes. His quick eyes looked around for something to help – Abdul. He saw the sack on Raamu’s chest and the bundles near Supad and Zunkaavu’s pillow, and ran towards them. Warned by the sound of Abdul’s voice, Raamu clasped the sack containing paper, his day’s income, even more tightly. David was angered by Raamu’s meanness in clinging to his rupee’s worth of paper scrapswhen a young man was dying nearby. He ran towards Raamu, who clutched his sack even more tightly and whined,

‘Dada, don’t take it. Don’t destroy an orphan like me. What will I eat tomorrow? … Take the old people’s bundle!’

He spoke from his heart, and used all his strength to hold on to his sack. The injured David found this intolerable; he was furious that a wretch like Raamu was defying him. In his anger he grabbed the sack, pulled it open near Abdul and set a match to the paper. He shouted, ‘Warm yourself! Warm yourself!’

Abdul felt better with the warmth of the fire and also from the sack that David had thrown over him; he felt better that death had retreated a little. Raamu’s desperate words rang in his ears and so he wanted to throw the sack from his body; but because of the force of David’s personality, he dared not do it. Meanwhile, David was looking at the dejected Raamu; the boy’s pathetic words had pierced his benevolent heart and he stood there, wondering how to repay him.

His standing there made Abdul restless; the couple Supad-Zunkaavu, chilled to the bone, just wished he would go away; and just then the beggar-woman, who had lain down among the bushes so that she could cast the life within her on the ground, let out a howl of pain. That howl made David tremble like a tautened wire. As he moved away, Zunkaavu and Supad gathered their blankets about them and came to sit by the fire. They collected the scattered papers of Raamu’s earnings and dropped them on the fire one by one as they warmed themselves. The cruelty made Raamu so angry that he wanted to smash a rock into their heads.

As he looked for a sizeable stone, the old couple warmed themselves and the pregnant woman let out shriek after shriek. David’s crazed movement speeded up with every scream of hers; each step he took caused him pain as the cold wind stirred up a fire in his wounds. He walked faster and faster, squeezing the dagger.

And now that her child had come very close to the earth, the first-time mother shrank with shame to see this enormous man advancing towards her. Her body seemed to shrivel up; the child’s rhythm faltered, and the woman longing to see her child and find release from her pain cried out,

‘Eh — don’t come here, turn back…’

The harsh distress in her voice slowed him down to a stop. He shouted: ‘Who are you, you whore, to stop me? If you speak like that again I’ll break your jaw.’ He came forward. The red mess between her thighs made him shudder in disgust and fear then turn around. Face turned away, eyes shielded, he began to walk away. When he had gone a few paces, he realised that he had done nothing to help her, and he stood still where he was, thinking. But he could not think of what he could do to help her. He opened his eyes to see if any help was at hand. But the cruel sight that met his eyes drove all thought of helping the woman out of his mind.

He could see the old couple Zunkaavu and Supad, driven desperate by the cold, trying to snatch Raamu’s remaining paper-scraps they could burn. They were hitting him, flailing him on the nose and mouth. David began to run, intending to bring the couple back to their senses. The couple paid no attention to his threatening shouts. Even before David reached them, they began to attack the boy with their hands, trying to snatch the paper from him. In his anxiety that they should not kill him, David ran, pushing people out of his path. They, in turn, seeing the dagger in his hand, lay quiet after he pushed or trod on them. Meanwhile, the old couple had defeated Raamu and were taking the old newspapers and tarred brown paper to the fire. Raamu quickly picked up a large boulder and brought it down on the head of the old woman. The old woman collapsed; instead of attending to her, the old man turned on Raamu. Seeing the old man advance murderously, a scared Raamustepped back, picked up two rocks. Raamu was so angry, so frightened, that if the old man had taken even one step towards him, he would have smashed his head and face in. Knowing that a man can be driven by fear to do the most terrible things, and not wanting the young Raamu’s life to be wasted like his own in jail, David roared,

‘Come, boy, put down those rocks. Will you do it or shall I smash your face in?’

Raamu put down the rocks out of fear of David. He turned his attention to the old lady, knowing that the old man would beat him for it. The old woman’s eyes were red with blood. The sari on her back and over her head were soaked in blood. The sight of the blood made Raamu turn his head toward David and blubber. The sight of that innocent orphan’s tears made David want to hug him. Like the Christ, he stepped forward with his compassionate arms spread wide. Just then, he heard a radiant, fragile note calling to him. A child’s first cry.

The feeble cry of the small child agitated his heart. The desire to see the child, to see its glowing flower-like face, kept him from Raamu. It pulled him back. It increased his restlessness. The arms that had been raised to embrace Raamu dropped to his sides. He stood there like a blackbuck, tensing his neck and eyes, pricking up his ears to detect the sweet note of the child’s crying. But for a long time, the sound did not reach his ears. And into his mind, still dazed from having witnessed man’s inhumanity to man among the people on that ground, grew a new doubt: Why does the child not cry? Did its mother, turned beast-like in this merciless cold, eat it up like a cat does? Or did she kill it to destroy the evidence of her sin…?’

The suspicion confused him. He turned his back on Raamu and walked away, agitated. And Raamu, who was longing to lessen his burden of suffering in David’s embrace, was hurt by seeing David walk away. His piteous eyes followed David’s rapid gait. And David, thrown off balance by this sudden rush of human feeling, concerned only that the intense cold should not drive the woman to cruelty, that she should not grow wild enough with grief to kill the child, walked on, pulling blankets off those in his path. And each man he suddenly exposed sat up distracted. Seeing the cruel hard dagger in David’s hand, and the power in his body, he would shiver with cold and remain silent. And David, breathless, savage, shouted, ‘Get up! A woman has delivered a child… the time of Christ’s birth was a time like this…’

He no longer knew what he was saying or doing. He was shouting, pulling off blankets from anyone he saw and piling them on his shoulder. He trod unthinkingly on anyone lying in his path, and as a tumult arose among the people on the ground, this giant of a man reached the leper from Madras. At that moment the leper, imagining the little pup in front of him to be his full-bodied wife, kissed and squeezed it; and just then David pulled the smelly blanket off his body, kicked him, and walked on.

His dreams suddenly divested of colour, the sharp lash of the cold, and David’s heavily-booted foot coming down on his gangrenous leg, angered the leper. He got up, picked up the piece of slate he used as a pillow, and ran at David with a filthy curse.

David, not used to being sworn at and assaulted by such an insignificant person, turned around. Shielding the dagger capable of slashing diagonally from the left side of a man’s chest to his right groin, he ran at the leper. Seeing the fiery gleam in his eyes, the leper stepped back. When David saw the swollen disfigured face of the leper his mind was filled with revulsion; disgust at the thought of dipping his dagger into his rotten blood caused him to lower his arm. He spat derisively, turned around and walked away.

Seeing the pride of an elephant in David’s gait, his tall broad muscular body, the leper’s chest burned with jealousy. The derision he had shown him made him want to murder him; and when David scornfully cast off the load on his shoulder, the leper, blind with rage, smashed the slate in his hand into David’s head. And David, who was sorely wounded from the morning’s assault, who had lost a lot of blood and was fired up only by his inner strength, suddenly collapsed. And at once, the people on the dusty ground, who had been inhumanly exposed to the bitter cold, set upon David and began to beat him, and the effort of hitting him brought warmth to their bodies and joy to their minds.

And now David, who had lived for so many years terrorising others but remained untouched like fire, was beaten by the people on the ground. He lay on the ground in the dust like some huge stone god, covered in blood, completely still. And each man who had grown elated with the effort of beating him now hunted amid the load tossed off his shoulder, for his clothes, his blankets, his sheets; squabbling as if in a dogfight, shouting, roughly pushing others aside. And the young mother who had just given birth among the bushes laboured to dig a pit with a sharp stone so that she could bury her blood-soaked clothes and the baby’s umbilical cord. The cold grew more intense, stirring up emotions of hatred and envy in the hearts of the people on the ground, driving them beyond the bounds of humanity.

Read the original Marathi story here.