As a woman talking about womanhood, I often find myself struggling in a world that is made up of conflicting messages about who a woman is, or who she should be. People around the world continue to reinforce misguided views about women. Even in the 21st century, women are excluded from discussions on war or national security, and are mostly presented with issues regarding health and family life. Why is it so difficult to detach women and family? Why is the woman so often judged by her remarkable ability to juggle her family, her career and her personal life?

To take the journey of the ‘ideal’ woman is to be someone’s daughter, then someone’s wife, mother, grandmother and so on. Even her family name says nothing about her; it first belongs to her father and then to her husband. As she enters the new family, she changes her way of life — from a receiver, to a giver, a giver of life.

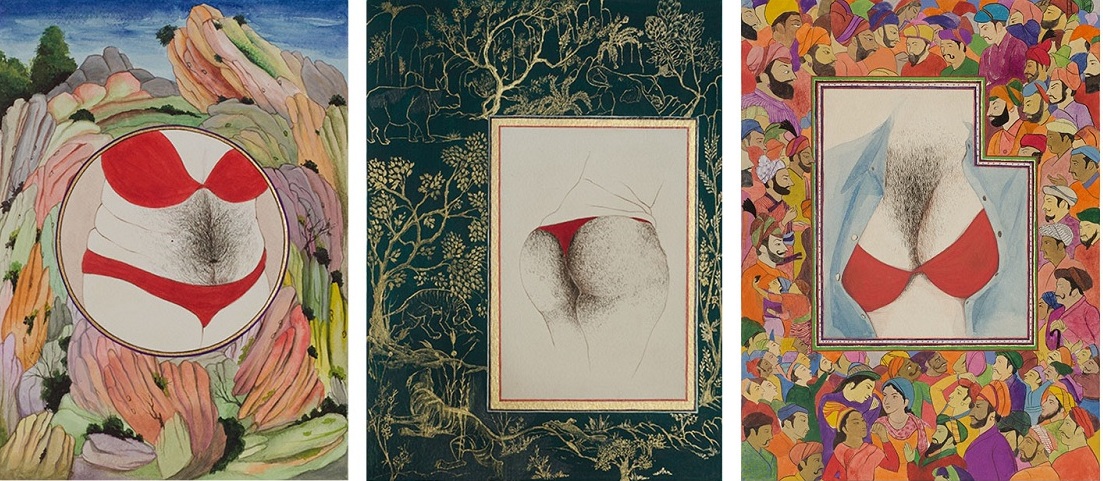

Appropriating a variety of familiar motifs and themes from both Indian and Western pictorial tradition, I re-contextualise them in light of the contemporary issues at hand. I deliberately combine icons of ‘high’ art and art from mass culture with wit and irony to redefine their role as cultural signifiers. I take advantage of a range of media — from gouache to performance, digital prints, video, and serigraphy to articulate my ideas. The hybrid character of my work subverts the obsolete ‘tradition/modernity’, or ‘Indian/western’ dichotomy. It undermines the perception of art as a mirror that reflects a state of cultural purity, and underscores its discursive character shaped by history and culture. I felt the necessity to understand constructed feminine qualities, behaviour; and the stereotypes associated with the image of the ‘ideal’ woman. So, I started exploring taboos that determine and control this image.

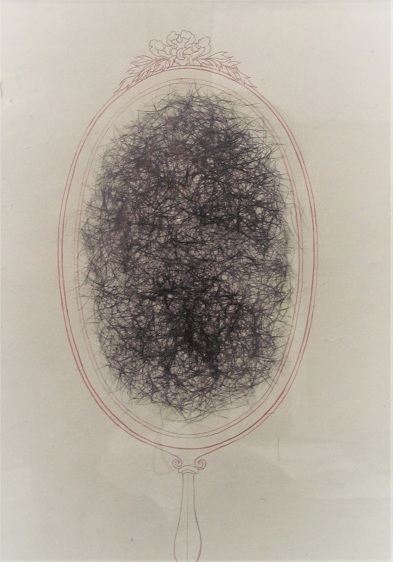

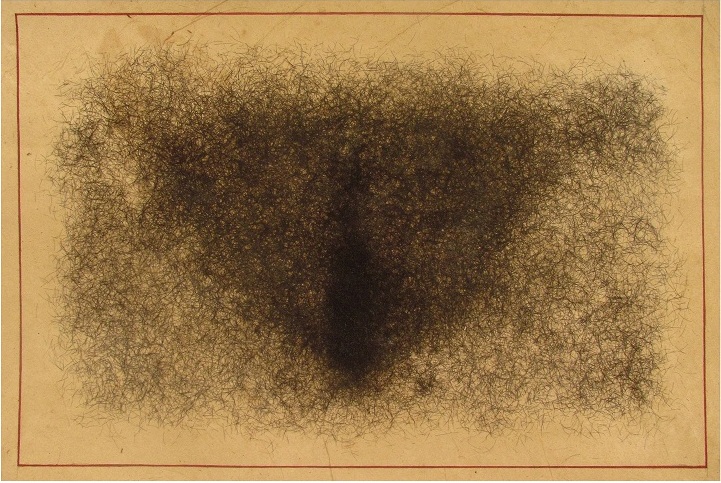

‘Mirror Mirror on the Wall’ and ‘Hairy’ explore the delicate space of feminine beauty, its valorisation and exploitation in modern society. I cover the space where the mirror ought to be, with my own hair, creating visual discomfort. The unnatural presence of hair and its celebration suggest that presence or absence of hair on a woman’s body has nothing to do with beauty.

‘Mirror Mirror on the Wall’, artist’s hair and water colour on tea-washed wasli, 24 x 30 inches, 2015

‘Mirror Mirror on the Wall’, artist’s hair and water colour on tea-washed wasli, 24 x 30 inches, 2015

‘Hairy’, human hair and water colour on wasli, 20 x 30 inches, 2013

‘Hairy’, human hair and water colour on wasli, 20 x 30 inches, 2013

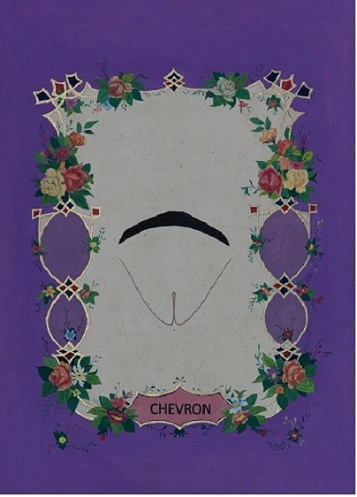

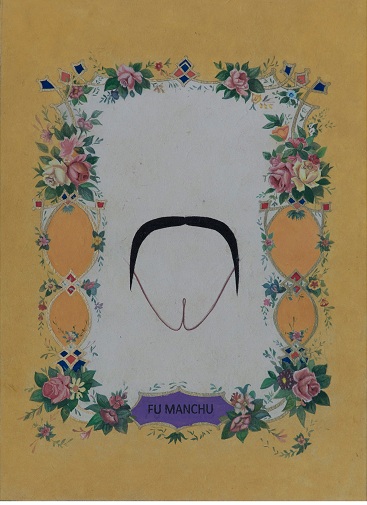

The idea was conceived when I was working on a series of five drawings titled ‘Chevron’, ‘Dali’, ‘Fu Manchu’, ‘Handlebar’, and ‘Imperial’ where I replaced pubic hair with moustache. Allegorically, I represent the difference of power in terms of the position of a single element of hair which is both personal and political.

‘Chevron’, opaque water colour and velvet on wasli, 10 x 16 inches, 2013

‘Chevron’, opaque water colour and velvet on wasli, 10 x 16 inches, 2013

‘Dali’, opaque water colour and velvet on wasli, 10 x 16 inches, 2013

‘Dali’, opaque water colour and velvet on wasli, 10 x 16 inches, 2013

‘Fu Manchu’, opaque water colour and velvet on wasli, 10 x 16 inches, 2013

‘Fu Manchu’, opaque water colour and velvet on wasli, 10 x 16 inches, 2013

‘Handlebar’, opaque water colour and velvet on wasli, 10 x 16 inches, 2013

‘Handlebar’, opaque water colour and velvet on wasli, 10 x 16 inches, 2013

‘Imperial’, opaque water colour and velvet on wasli, 10 x 16 inches, 2013

‘Imperial’, opaque water colour and velvet on wasli, 10 x 16 inches, 2013

Hair on the human body, especially on the body of a woman, can have various interpretations. In earlier times, Hindu women used to sacrifice their hair – a symbol of beauty and bounty — and offer it to the Almighty after losing their husband. This was done to strip the widow of the ‘stigma’ of beauty after the husband’s death. My work ‘Nether Regions’ is a simulation of the traditional ‘alpana’ (a form of floor decoration specially done by women in the house.)

‘Nether Regions’, human hair and acrylic on canvas, 72 x 72 inches, 2017

‘Nether Regions’, human hair and acrylic on canvas, 72 x 72 inches, 2017

‘Nether Regions’ generally indicates the lowest parts of a place, or someone’s body, that is, the genitals. In the process of the work, when I cut my head’s hair into small fragments, and was covering the spaces between the contours of the work with them, it seemed as though this hair was transforming into pubic hair. We’re living in an era when leaving your pubic hair untamed is so unusual that ‘hairy’ has become a form of niche pornography – it is considered dirty, ugly, sexual and animalistic.