Two containers; 12cms x 7cms (length x diameter); glass; 2016

Two containers; 12cms x 7cms (length x diameter); glass; 2016

The diction hole, water boy lessons

The philosophical hole for a litmus test

The set of glasses underlines two different notions:

One is connected to the household disciplinarian and the latter to the worldview of an individual.

The practice of filling drinking water to the brim makes it difficult to drink causing the water to spill on the drinker. The diction hole works as a corrector to the language of filling water.

The other glass underlines the overused pessimist-optimist debate of the glass being half-empty or half-full. The given reality is further stagnated by the introduction of the hole, which also disables the idea of a filled glass. In both the cases, the hole acts as temperance to the existence of the water in the glass.

The former idea underlines the routine act and its disciplined water level thus projecting the concern of an individual towards the politics of the domestic. The latter philosophical stagnant lays out the concerns of an individual towards a social spectrum based on his/her personal view. This attitude is common to all kinds of socio-cultural-political backgrounds. The object deals with both inward and outward human behaviour.

The Poetry of a Taper

Finally, and this is perhaps their loveliest function, the chopsticks transfer the food, either crossed like two hands, a support and no longer pincers, they slide under the clump of rice and raise it to the diner’s mouth, or (by an age-old gesture of the whole Orient) they push the alimentary snow from bowl to lips in the manner of a scoop. In all these functions, in all the gestures they imply, chopsticks arc the converse of our knife (and of its predatory substitute, the fork): they are the alimentary instrument which refuses to cut, to pierce, to mutilate, to trip (very limited gestures, relegated to the preparation of the food for cooking: the fish seller who skins the still-living eel for us exorcises once and for all, in a preliminary sacrifice, the murder of food); chopsticks, food becomes no longer a prey to which one does violence (meat, flesh over which one does battle), but a substance harmoniously transferred; they transform the previously divided substance into bird food and rice into a flow of milk; maternal, they tirelessly perform the gesture which creates the mouthful, leaving to our alimentary manners, armed with pikes and knives, that of predation 1.

The above passage from Barthes’ Empire of Signs creates a harmony between the food and its instrument (object). Barthes delicately portrays a version of the chopstick caressing the food before it is chewed, swallowed, digested and excreted. The body’s system of perceiving its consumable nutrients, in fact, takes the form of an inverted chopstick.

This process can be visualised in the following way: The delicate tip of the chopstick represents the aroma and the sight of the food, leading to a careful picking up of the food which then mingles with the taste buds in the mouth with constant chewing. The middle taper represents the process of swallowing and the digestive system; and the thicker end projects the firmness of the process of excretion with that which is unnecessary, pushed out of the system. The taper in a given piece of wood allows each part to function independently while still belonging to the same system. The uselessness of the foreign hand converts itself into the slender extension of the tip rendering the person a disabled user of the beautiful tool.

53cms x 53cms x 6cms (length x breadth x height); found chair and lace; 2016

53cms x 53cms x 6cms (length x breadth x height); found chair and lace; 2016

53cms x 53cms x 6cms (length x breadth x height); rexine, foam and zipper; 2016

53cms x 53cms x 6cms (length x breadth x height); rexine, foam and zipper; 2016

Annoying Rebel

Annoying rebel is providing an escape route, but that’s a sex trap!

As power operates by enforcing spatial discontinuities, Timerman’s narrative of that single night demonstrates how resistance to power can overcome the authority of those interior segments. The resistance comes necessarily form within; it links inside to inside, and by doing this it compromises the authority of the two separate cells. The guard positioned as a functionary, attached to a sovereign state that rules by enforcing the interiors. His job is to maintain separations. Thus, by leaving the peephole open, he becomes a spatial revolutionary — a minor architect. “Not following the rules,” he abets an act of escape for Timerman and for the unnamed prisoner across the corridor2.

These escape openings layer the body as its artificial skin. These expect that not just the organ, but the entire body would flow through them. Their temporal gestures merely function as cat-doors of the house.

Anti-Antimacassar

‘Let us live forever into the newness of things.’

The hyperbolic sound of the sentence underlines the way we try to define the permanence of our selves and our collectibles.

He reasserts that it is the relationship of the collector to his or her objects that is important to the collection because “the phenomenon of collecting loses its meaning as it loses its personal owner,” no one will be able to order a collection with the same understanding that the original owner did (67). Collections can tell, for the collector, not only the historical story of the object itself but also the story of the collector — “ownership is the most intimate relationship that one can have to objects. Not that they come alive in him; it is he who lives in them.”3

The objects form the third layer of the house — the first layer being made of the walls and the second layer comprising everything from a stain to a scroll (nail of the scroll) on the wall. The three layers of the ‘things’ express their age and intimacy with their respective owner. If a wall is populated with screw holes, it would then not talk about the act of violence, but rather, reflect the popularity of the wall, the owner’s desperate attempts to present a suitable background to his favourite collectibles. The discoloured handle of the tea pot translates into the age of the palm; and the collection of various lids in the kitchen drawer narrates the impermanent and fragile nature of the pot, marking the owner as a devoted tea-drinker. The value of objects lies in their age rather than their newness; born as sterile, the things slowly adapt to a life breathed into them by their owners.

The stitched line with the crocheted borders de-marks the absence of negative space, the missing antimacassar.

50cms x 25cms (length x breadth); brass; 2016

50cms x 25cms (length x breadth); brass; 2016

Time on Slopes

The valley of ‘zero slopes’

Contains layered time

Time on the slopes keeps recycling

The aged object

Self-reflective, matter to form

Uselessness is the aesthetic

The thin horizontal is still a slope where

Vertical time slips.

6cms x 10cms (height x diameter); glass jar; 2016

6cms x 10cms (height x diameter); glass jar; 2016

Travelling cream

Moves perpetually in its stillness

But Eliot’s jar rejects such philosophical and spatial authority. Making no claim to either truth or power, it “moves perpetually in its stillness.” Its vibrations are speech at its most primitive; Deleuze might have said that the jar began to shutter. Or in Kafka’s universe, it might emit nearly silent sounds like the incessant humming of the mouse Josephine. At the threshold of relinquishing all objectivity and object status, the vessel is actively becoming contingent. Like the prose of Finnegans Wake that hums along for 600 pages, Eliot’s jar represents twentieth-century cultural transformations in which motions replace meaning, and sounds replace sense4.

Jill Stoner describes Eliot’s language as something that offers doorways for producing the minor; it lets countless movements overlap with itself to define the eventual movement of stillness. The object becomes the metaphor of the shifting space around it. On the other hand, the stillness of the object stands the test of the timeline it has been balanced on. The object narrates the fictional story of a journey that has shaped its reality in the moment of complete stillness.

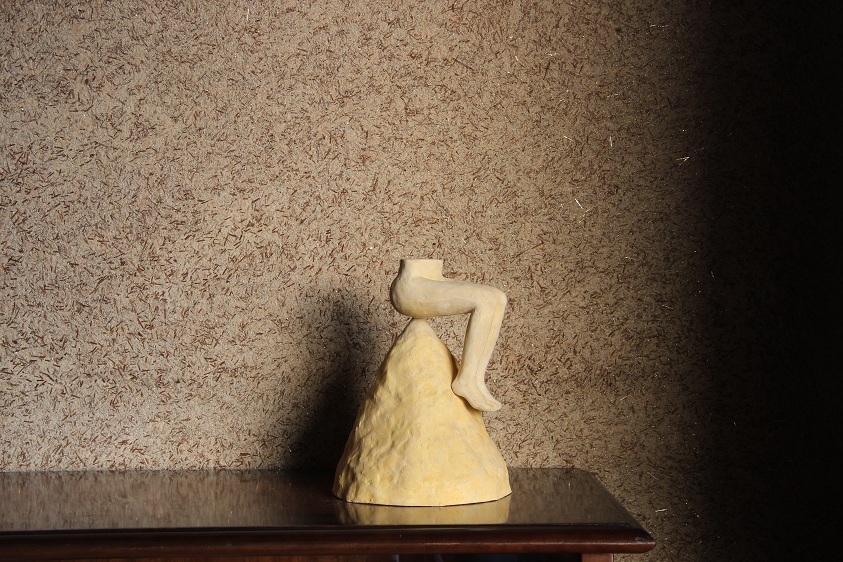

22cms x 19cms (height x diameter); dental plaster; 2016

22cms x 19cms (height x diameter); dental plaster; 2016

22cms x 19cms (height x diameter); dental plaster; 2016

22cms x 19cms (height x diameter); dental plaster; 2016

Montaigne’s El Caganer in Tanizaki’s Toilet

“To learn that we have said or done a stupid thing is nothing, we must learn a more ample and important lesson: that we are but blockheads… On the highest throne in the world, we are seated, still, upon our arses.” And, lest we forget: “Kings and philosophers shit, and so do ladies.”5

In his essays on philosophy of the self, Montaigne evaluates every living being based on scatological theories which render them equal, further clarifying that the philosophical state does not exceed the human condition. In In Praise of Shadows, Junichiro Tanizaki highlights the ritual of defecating by talking about the architectural importance of a Japanese toilet in a traditional Japanese household.

Anyone with a taste for traditional architecture must agree that the Japanese toilet is perfection. Yet whatever its virtues in a place like a temple, where the dwelling is large, the inhabitants few, and everyone helps with the cleaning, in an ordinary household it is no easy task to keep it clean. No matter how fastidious one may be or how diligently one may scrub, dirt will show, particularly on a floor of wood or tatami matting. And so here too it turns out to be more hygienic and efficient to install modern sanitary facilities — tile and a flush toilet — though at the price of destroying all affinity with “good taste” and the “beauties of nature.” That burst of light from those four white walls hardly puts one in a mood to relish Sōseki’s “physiological delight.” There is no denying the cleanliness; every nook and corner is pure white. Yet what need is there to remind us so forcefully of the issue of our own bodies. A beautiful woman, no matter how lovely her skin, would be considered indecent were she to show her bare buttocks or feet in the presence of others; and how very crude and tasteless to expose the toilet to such excessive illumination. The cleanliness of what can be seen only calls up the more clearly thoughts of what cannot be seen. In such places the distinction between the clean and the unclean is best left obscure, shrouded in a dusky haze.6

The mountain of faeces

Positions the mountain maker

On its pinnacle

The pinnacle is in a state of flux while

The El Caganar is listening to Mozart’s

Canon in B flat for six voices

90cms x 42cms (height x diameter); cloth and wood; 2016

90cms x 42cms (height x diameter); cloth and wood; 2016

90cms x 42cms (height x diameter); cloth and wood; 2016

90cms x 42cms (height x diameter); cloth and wood; 2016

80 Meters of Clothe for Sol Lewitt

An object is a living being that is in a state of metamorphosis, establishing a dialogue with its recipients.

The frequencies are layered underneath the given visual framework. Unlike Kafka’s beetle, they are unaware of their transformed state. They would stop changing if we stopped looking. These objects are primary causes of our thought-refractions — their identities or temporalities are based on the limitations of our understanding.