Sometime last year, I made a collaborative comic about artist Heather Dewey Hagborg’s DNA-portraits of US whistle-blower Chelsea Manning, at a time when Manning was still in prison, and nobody was allowed to take her photograph and slip them into mainstream world media. I was curious about how it came to be that prisons believed, with such certainty, that they could make a person disappear by stopping the continued supply of their photographic portraits.

Frame from the comic Suppressed Images/ Image courtesy Heather Dewey Hagborg, Chelsea Manning, Shoili Kanungo and the Thoughtworks Arts Residency

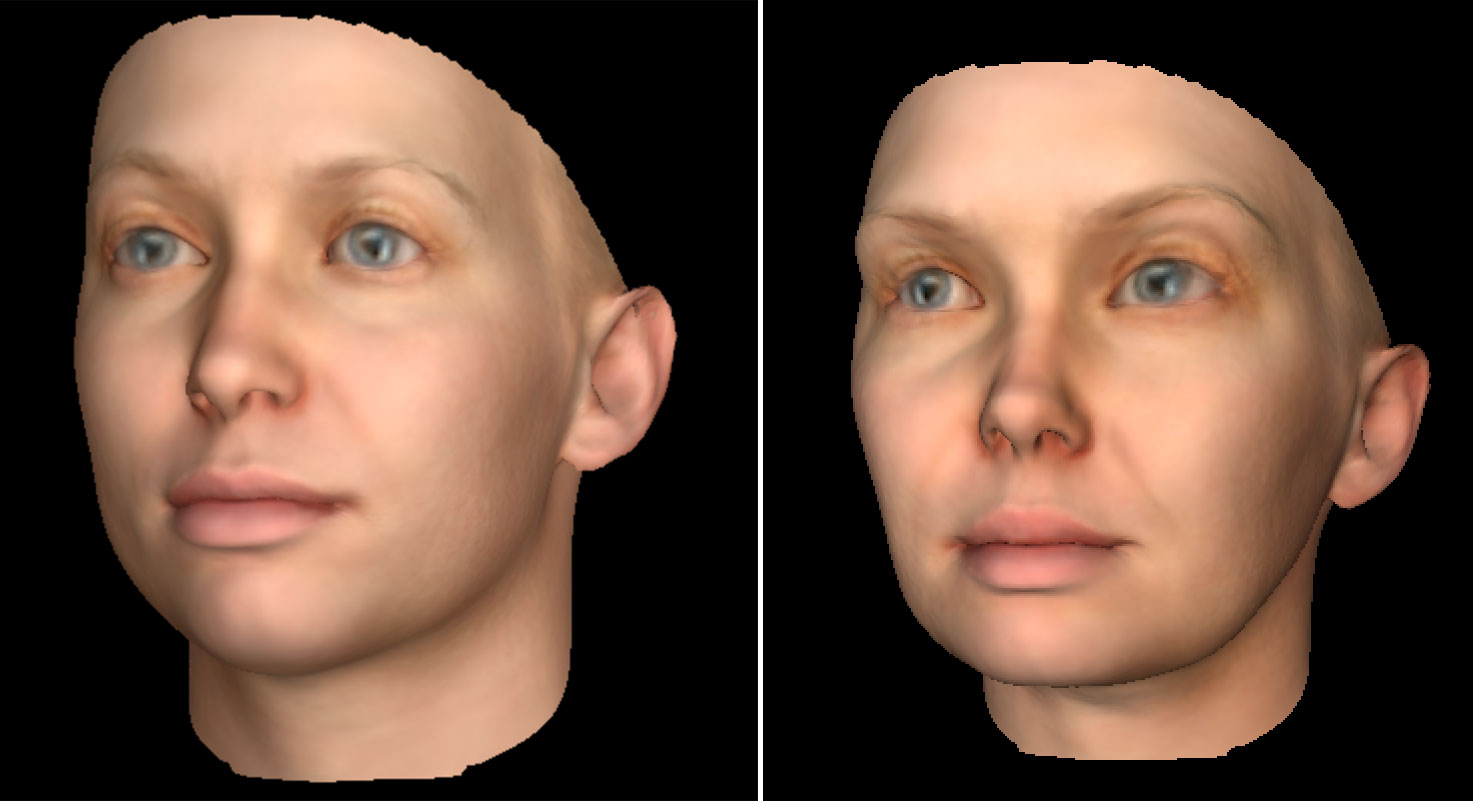

DNA portraits of Chelsea Manning created by Heather Dewey Hagborg/ Image courtesy Heather Dewey Hagborg

Photographs must be simultaneously scary and useful to law enforcers. In the courtrooms, forensic photography is used to extrapolate evidence from photos. In the early 20th century itself, people came to collectively believe that the camera box was a neutral machine that had no temperamental artist sitting within, and hence, it was well equipped to give an unbiased reflection of nature. And this is probably how courtrooms could justify the use of photographs as a source of evidence [1].

And just any photograph will not do. Photographs have to be styled in a technical way in order to be considered appropriate as forensic evidence. But, this forensic styling could conceal inconvenient truths — truths that might be revealed in an art-directed photograph, or a more subjective portrait. For example, the prison profile photographs of Manning were taken in the forensic ‘mug-shot’ style, as if determined to bleach out Manning’s personality: Harsh flat lighting, a plain background, front view, side view.

Sometime in May this year, after leaving prison, Manning released photographs of herself to the press. There she was, stunningly beautiful, one of many wonder women. She looked optimistic, energetic, and calm — someone who had weathered the storm and now gave us a slightly bemused half smile. It was the portrait of a hero and a role model. The photograph has been art-directed, and yet it seems to have captured the essence of Manning better than any technical portrait. Maybe, this is why the prisons were afraid to allow more portraits of Manning to emerge — it would mean allowing for the possibility of an interpretation of Manning contrary to what the prisons wanted to project.

Chelsea Manning in May, after her release from prison/ Photo via Instagram

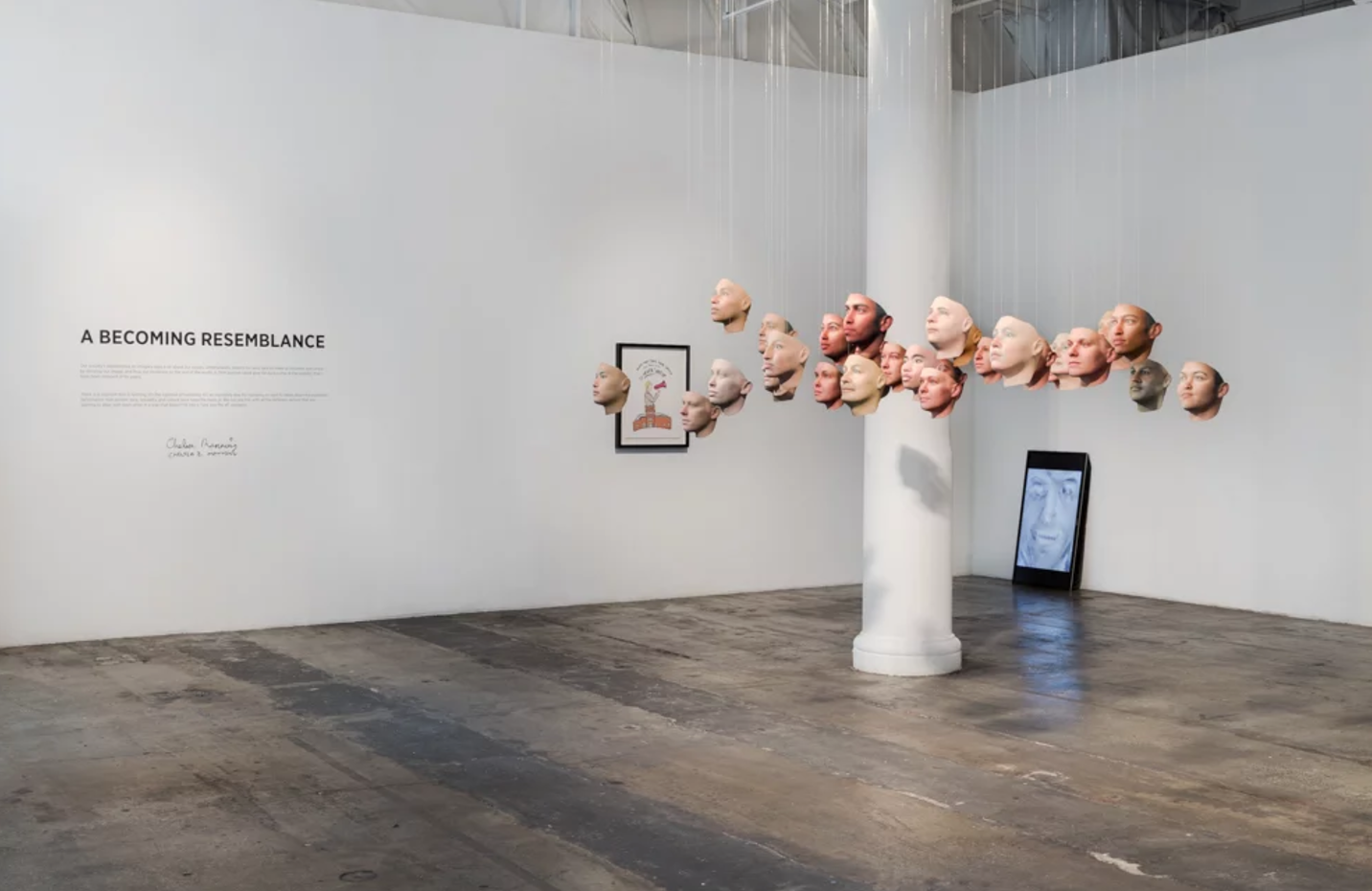

In addition, perhaps, the prisons hoped that people would forget about her if no new photographs were to emerge. In the age of the internet, we assert our identities with continuously updated profile photos. And those who have none, seem to have fallen into oblivion of a kind. This image-lacuna was felt in the case of Manning because artists came up with alternate representations. Heather Dewey Hagborg’s DNA-portraits are a powerful solution because they are the result of DNA that Manning had sent to Hagborg from prison, and there is an immediacy to this portrait. Given that we live in times when the DNA sequence is believed to be the axiomatic truth, this too could be viewed as a neutral and objective portrait, closest in power to a photograph. But is it really? This is precisely what Hagborg questions in her work, ‘Probably Chelsea’, in which she displays thirty possible portraits that can be created out of Chelsea’s DNA.

A series of 30 3D printed portraits of possible Chelseas. The installation ‘Probably Chelsea’ illustrates a multitude of ways in which DNA can be interpreted/ Image courtesy Paula Abreu Pita, courtesy of the artists and Fridman Gallery

A series of 30 3D printed portraits of possible Chelseas. The installation ‘Probably Chelsea’ illustrates a multitude of ways in which DNA can be interpreted/ Image courtesy Paula Abreu Pita, courtesy of the artists and Fridman Gallery

A series of 30 3D printed portraits of possible Chelseas. The installation ‘Probably Chelsea’ illustrates a multitude of ways in which DNA can be interpreted/ Image courtesy Paula Abreu Pita, courtesy of the artists and Fridman Gallery

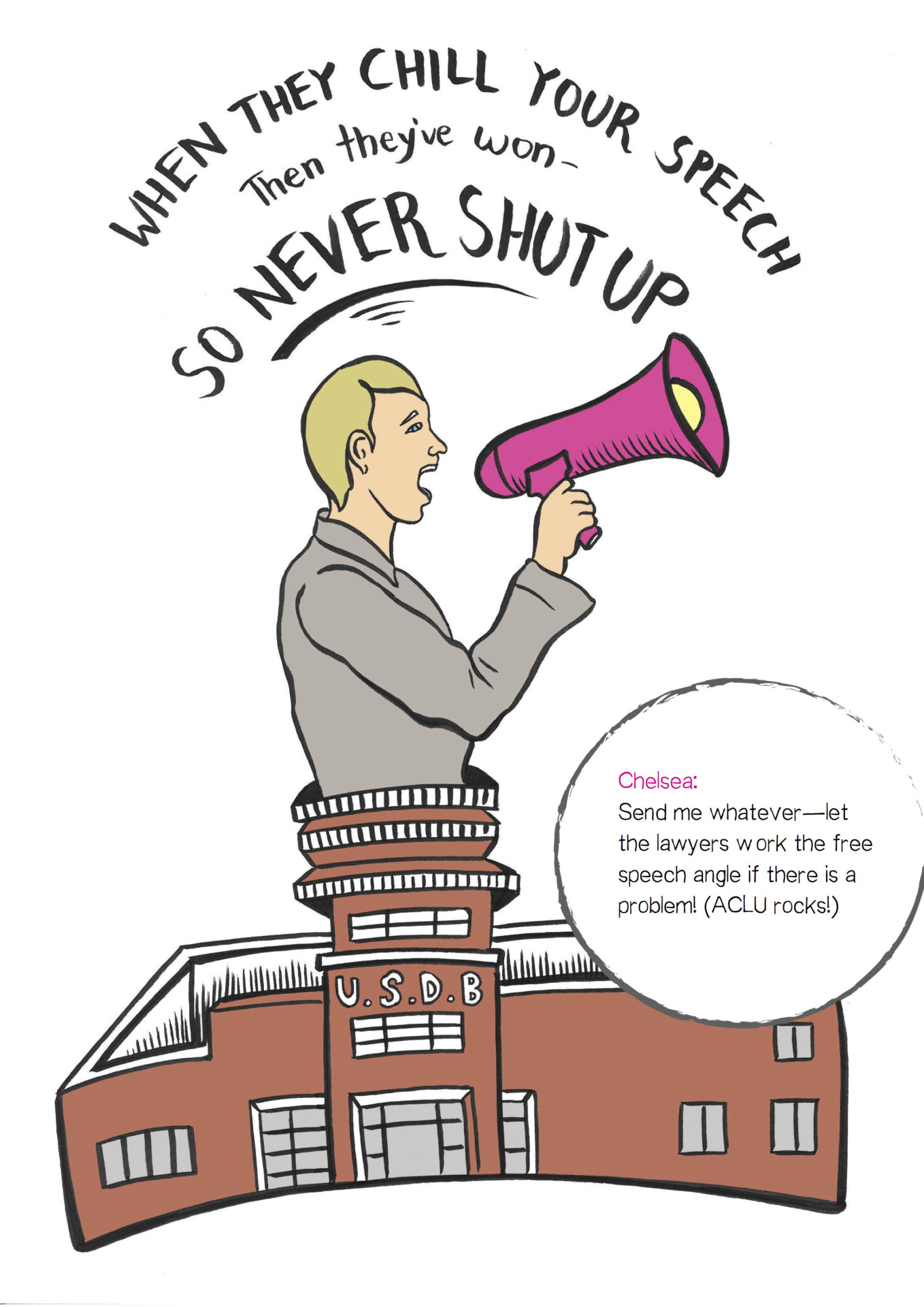

The creation of the comic led to the generation of another kind of portrait. I read some of the letters that Manning had sent to Heather from prison and one of the lines stood out particularly, ‘If they chill your speech, then they’ve won. So never shut up.’ For me, it encapsulated Manning’s unending courage and spunk, and I wanted to create an image to accompany her statement. I thought of Manning, always ready to speak her mind, emerging like a jack in the box from the United States Disciplinary Barracks where she was imprisoned.

Frame from the comic Suppressed Images/ Image courtesy Heather Dewey Hagborg, Chelsea Manning, Shoili Kanungo and the Thoughtworks Arts Residency

So finally, which of the portraits of Chelsea Manning is true, or more true? And what does that even mean? I think that we project upon the images we create, and view, vast worlds of truths that we already believe in. They may or may not be apparent in the image itself but the way we present an image enables that truth to emerge for the viewer to receive.

[1] The use of forensic photography is discussed in the following essays: The Construction of Visual Evidence by Diane Dufour; The Image of Truth: Photographic Evidence and the Power of Analogy by Jennifer L MNookin; courtsey to the Alkazi Foundation for the Arts.