Dayanita Singh’s ‘File Room’ is an elegy to paper in the age of the digitisation of information and knowledge. The analogue photographer and bookmaker has a relationship with paper that is integral not only to the work of making images, texts and memory, but also to a larger confrontation with chaos, mortality and disorder in the labyrinths of working bureaucratic archives in a country of more than a billion people. Including an interview with Hans Ulrich Obrist that relates this book with Singh’s other books and bodies of work, and texts by Aveek Sen that explore the different ways in which the world of files and paperwork continue to touch ordinary lives, ‘File Room’ is itself an archive of archives. It documents and reflects on the nature of paper as material and symbol in the work of making photographs and books.

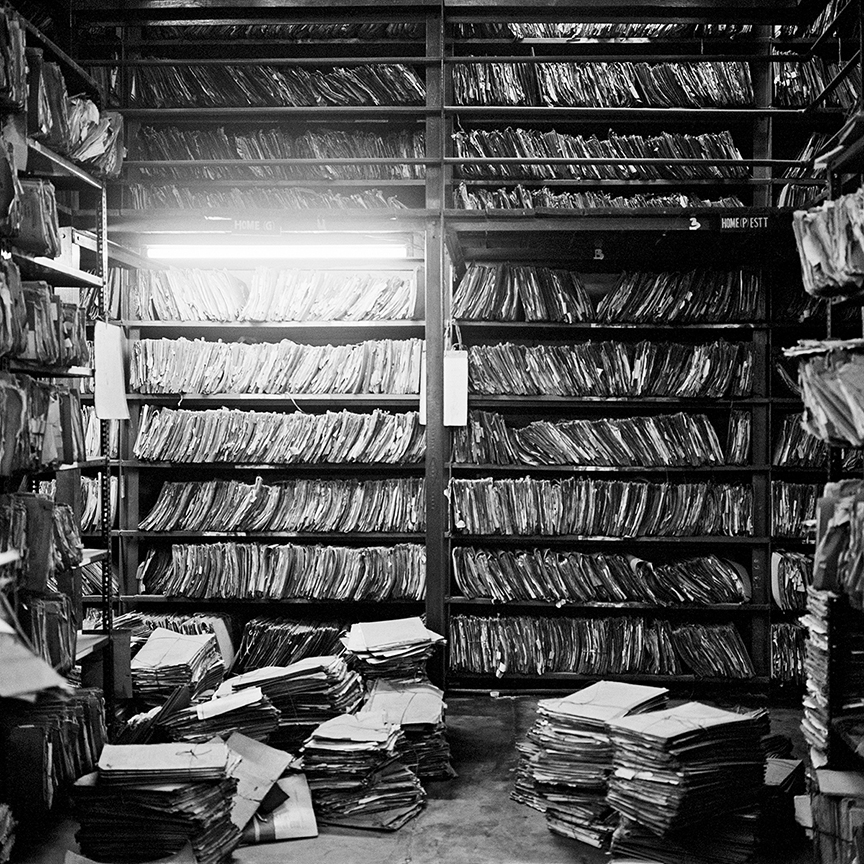

Sea of Files from ‘File Room’, 2013

Even before we could put the furniture back in place where my husband’s body had lain, the call from the lawyer came. The high court had given a final date for a case my husband had been fighting against the government. Mahinder was a farmer who had developed a strain of wheat that created a world record in yields. But the National Seeds Corporation was disputing his way of distributing the seeds. So, even before the four days of official mourning were over, the space that was cleared for his body in the heart of our home in Delhi got swept up by the deluge of files that tumbled out of each room. And, in a moment, I turned into a 42-year-old widow with four young daughters and more cases than I could count on my fingers. Gone in an instant were my days of painting and poetry, of being happy simply running the house, photographing the girls, and making numerous albums.

People told me I should be wearing white. But who had the time to think about such mundane things? There was no time even for mourning. I had to file my reply to the court in four days. I had lived with files everywhere in the house ever since I married Mahinder, but I was clueless about their contents. We lived in a huge old house that seemed to grow in an organic way, according to a mad logic that had little to do with plans. It was an expanding maze of rooms leading to rooms, where stores of wheat-seed, trunks full of who knows what, cupboards full of rusty fire-arms and property deeds, two stuffed tiger-cubs in vitrines and a two-headed snake in formaldehyde coexisted with four girls and a woman who found no time to look for her widow’s weeds. And in the midst of all this were the thousands of files.

Revenue files, court files, income-tax files. They filled up not only the office-room, but also our bedroom, guestrooms and shuttered store-rooms behind the house. Most of that domestic chaos of paper had to do with land, lost, recovered and about to be lost again – the hundreds of acres lost during Partition, a fraction of those hundreds wrested from the State as compensation, and the constant threat of their decimation by inheritance laws favouring sons over daughters. Loss, division, and the inequality of the sexes threatened to swallow up even this house we had now. Then, all of a sudden, it fell upon me to keep it all together.

When Mahinder was alive, he would often get ready in the morning and call me, Locate this file of mine! Locate that file of mine! And I would be looking around in the office and in the bedroom, bending on my knees or on all fours to go under the large writing table that was covered with a mountain of papers. I would go under it and around it and with great difficulty locate a file for the high court, or was it some lower court? It was a game of hide-and-seek that I played with the files, always keeping my fingers nervously crossed. But, in less than a week in the summer of 1982, that youthful game turned decidedly grim. I inherited three high court cases and around eight cases in three lower courts in two cities. They involved 98 lawyers over a period of thirty years. Each day, we lived in dread of the doorbell ringing and our getting another notice or summons.

So, I brought all the mountains of files that were lying in Mahinder’s office, out of our bedroom and the store rooms, into the drawing room where he had lain at the end. I started to place the files all over the room. The piles grew and grew until they turned into a sea of files, at the centre of which I would sit. I had low blood pressure, so getting up early in the morning was like a punishment for me. To this was added something like a fear of waking up. If I opened my eyes a little at six in the morning, in a second all the worries would crowd back into my head. I sat with my tea in the middle of those files and started working. I had my breakfast there, and lunch, made notes until evening, and carried on until dinnertime. My daughters stood and watched me, but there was no time to explain. I wanted to protect them as much as I could. I often fell asleep on the files and most of my daughters would wake me with startled faces. Most of the files were dusty and old and had thin paper in them that crumbled quickly. Rats would gnaw at them too. Nobody was allowed to touch them.

I remember how my father’s files remained his strange, but known, bedfellows, after he had retired from the army and the police. They lay closer to him than even his beautiful, calm and faithful wife. They lay like bombshells, in piles and mountains, around his bed, which I had designed according to his specifications. No one dared dust them, or even touch them, lest the method in their madness was lost.

I had to work out a way of organising my files, keeping the plaints, applications, originals, copies and court orders separate, because once a piece of paper got lost in that vortex in the middle of the house it was impossible to find it again. In that kingdom of files, the battle was not between good and evil, but between order and chaos. An army of different files tried to keep the unruliness of paper under control. Box files, files with or without flaps, files which were just pieces of cardboard with pyjama strings fixed to them, ripple files, cobra files, lever files, index files, triple-extra-thick office files. They had names like Solo, Diplomat, Moot Point, Blue Sky and Moonlight.

Sometimes I had to make different combinations of papers for different lawyers and I would tag each combination with slips of paper and use page-marks of different colours, so that I could quickly get to what I needed in the rush of a courtroom. There were two long, deadly-looking needles of steel and iron, called a baksua, for punching holes in the papers, a job that demanded all my strength. Another punching machine looked like a large toad on the floor, and I put paper in its jaws and had to stand on it with the full weight of my body to make it punch holes. There were different kinds of paper too, each with its own smell and speed of decay: thin typing paper that crackled when you moved it and became crumbly in no time, court paper that was strong and watermarked, and cheap yellow-brown paper of which most of the court files were made, which quickly became brittle and grimy. At home, I started making my own bundles of files and papers, first with old sarees and then with markeen, the cheap cloth of unbleached cotton that sofa-makers nail to the underside of sofas. 1½ yards to make a bundle of files sit tight, 2½ to tie a body for the pyre, and worn by the eldest son as he lights the pyre and begins his mourning.

I soon started attending all the court hearings myself. This meant regular visits to the Tis Hazari and Patiala House courts, the high court of Delhi, and those terrible offices of the tehsildars and patwaris, dusty and dirty, with the huge stacks of files, old, half-torn and half-eaten, lying around everywhere. Who would ever manage to find a file in this mess? Yet, there would be an old man who knew exactly where, under which pile, to look for a file. Sometimes, I would peep into an empty courtroom and find a young woman typing away, sitting alone among helter-skelter chairs, the walls around her lined with steel cupboards and compactors full of files. After the courts closed for the day, there would often be long waits in lawyers’ offices. I kept one of Mahinder’s last-tied turbans in the car, and when I had to drive back home alone at night, I would put it on so that people might take me for a man at the wheel.

However much I hated files, at least mine were cleaner. I didn’t like the piles of dirty files lying about in heaps in the courts, so that I had to pick my way through them on the landings of the narrow backstairs. Imagine climbing three flights of stairs in Tis Hazari (there were no lifts then), clutching maybe ten files in my arms, which were more used to holding babies that were not quite as heavy. I would be standing in front of the office of some unsavoury old officer. There were no fans, so I was hot and sweating , and this man would be sitting inside nicely, not calling me in even after I had sent in a slip of paper with my name on it. People would walk in and out of the office, but I would stand at the door as if I were invisible. The files that I had to bring to court weighed ten or fifteen kilos, and I carried them in large canvas bags.

After some months, I got frozen elbows, especially on my left arm. My orthopaedic asked me if I was left-handed or had started playing tennis. Then, the real cause occurred to me. It took a great deal of stamina to run behind the lawyers in court. They were always in a hurry and ran ahead of me, their black coats flapping and flaring, and I would run behind them with a bag of files in each hand, trying to catch up. I did not mind when they said among themselves in the courts that I was not a woman, but a man.

Delay and waiting became the stuff of my life, keeping everything else on hold. Sometimes, my number came up too late in court, just before lunch-time. Would I be called again after lunch? No, sorry, at four o’clock the courts wind up, and I would have to wait for the next date, when I would come again carrying those files, and the hearing would again be adjourned to a later date, on which the lawyer for the other side wouldn’t turn up. Sometimes, there would be a bomb scare or a blast somewhere on the premises, and the courts would shut down suddenly.

During the anti-Sikh riots of 1984, as the mob approached our house with burning tyres late in the night of 30th November, I quickly destroyed the give-away nameplates with Mahinder’s name on them (Why must Sikh men have such long names? I wondered in my panic). I took the cheque-books and the jewellery from the cupboards, as I had seen my parents do during Partition, and made my daughters cross the road, one at a time, to the house of our courageous Hindu neighbour, who had offered to give us shelter. But I knew I had to go back and fetch the files. I waited until the mob was distracted by a passing bus, ran across the road and rushed back clutching my files. The bus was in flames. I suppose it had Sikh people inside.

If you walk about in the courts, you will realise in no time that everything in them is designed for waiting without hope. But you find yourself waiting with a stubbornness that begins to look like addiction to those who are out of all this. There are toilets everywhere, limbo-like waiting areas with rows and rows of chairs, stalls for books, magazines and food, even a dispensary. And the floors are identical to one another. If you climb a flight of stairs to the next floor, you would think you’re back in the same place again. Thank god, my cases are mostly in the high court, I thought. At least it is air-conditioned, and there are sofas I can sit on. I would go off to sleep on a sofa if I had worked until late on the files the night before, to be woken by a lawyer calling me to attend or, if that did not happen, to tell me to go home.

Every time people asked me, How are your cases? I would say, In the courts there is no justice, all you get are dates, dates and nothing but dates. Of the twelve or so cases I was fighting, I had won just one in these thirty years.

I used to think that I owed this fight to the ancestors who had left this land and property to us. They had left us their legacy, and it was my duty to pass it down to the next generation. But, sitting amidst the ocean of files late in the afternoon one day in that house of five women, with the now-quite-usual sickness rising up in my guts, I realized that this battle would never end. If I did not call it quits now, the only inheritance I would be handing down to my daughters would be this nightmare without end and my wilderness of files. People ask me why I gave up. To give up, I tell them, is the only way out of this country of perpetual stay orders, this land of status quo.

Aveek Sen