Himmat was formed in the wake of the state-sponsored genocide of Gujarati Muslims in 2002: it was at the time a collective composed of riot-affected women from Naroda Patiya. Its co-founders Monica Wahi and Zaid Ahmad Shaikh introduced Baroda-based artist Vasudha Thozhur to six girls Himmat was working with – Tasleem, Rabia, Farzana, Shah Jehan, Rehana, and Tahera – all of whom had lost their families in the massacre. They were aged 12–19 at the time. We are proud to share with you a glimpse of the decade-long art project that followed.

Our walkthrough of an exhibition, held at the Jawaharlal Nehru University in 2015, of the art that emerged from Himmat

Narratives of Strength and Survival / An Archive

The Himmat Workshops

Funded by the India Foundation for the Arts

Himmat Centre, Mayur Park, Vatva

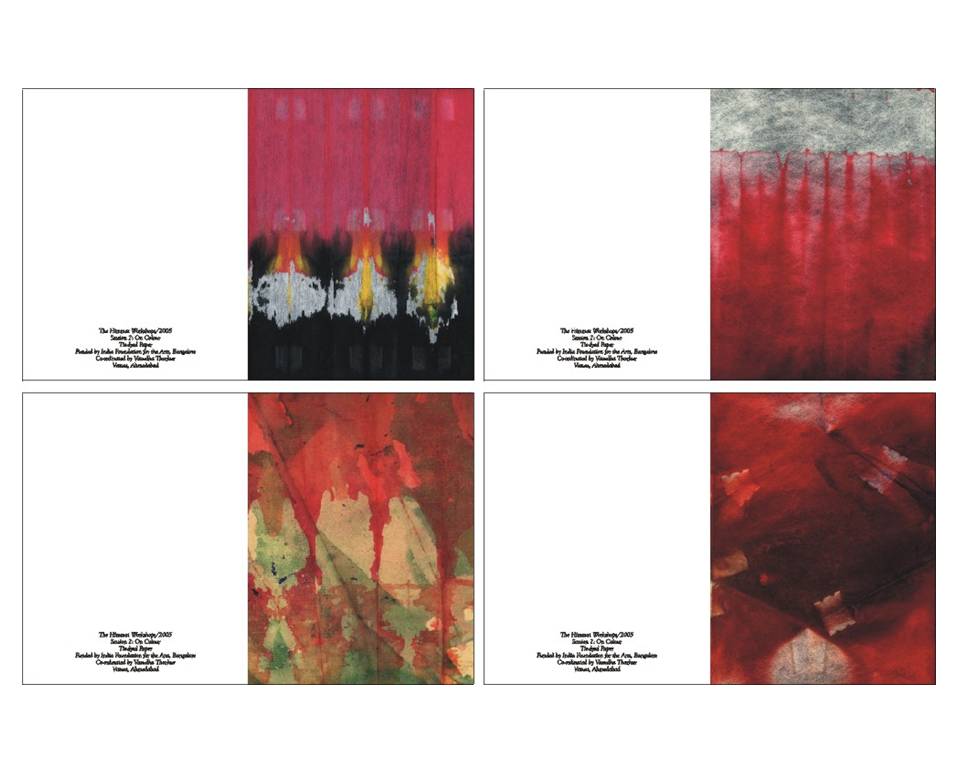

January 2005 / Posters The first couple of sessions that we did dealt with colour – we started with marbling on paper, some tie and dye, some drawing, printing with vegetables, collage with fabric. We made bookmarks combining the vegetable prints and fabric collage. There were sacks full of scraps of waste fabric at the Centre in which we used.

The girls were given notebooks that they could draw or write in, so they could keep records of the process.

We went on a visit to the Kanoria Art Centre, where we met Sharmila Sagara who invited us to participate in the art festival that was scheduled for February. We also visited the National Institute for Design, where the staff took us around. We had the benefit of short demos in every department, and interactive meetings with the students.

Azra Khan came over from Baroda on the last day as a resource person and showed the girls how to make stationery, and some simple book-binding techniques.

With the output from the first session, we made posters for the sale of garments which Himmat had organised in Bangalore and in Goa.

Later, we sold six of these to Oxfam and with the proceeds, we started literacy classes for the girls. A local resource person, Shahana, was willing to conduct the classes, for an hour and a half every day.

The girls began their sessions and by May were able to sign their own names.

Shah Jehan Shaikh, Untitled, 2005

Shah Jehan Shaikh, Untitled, 2005

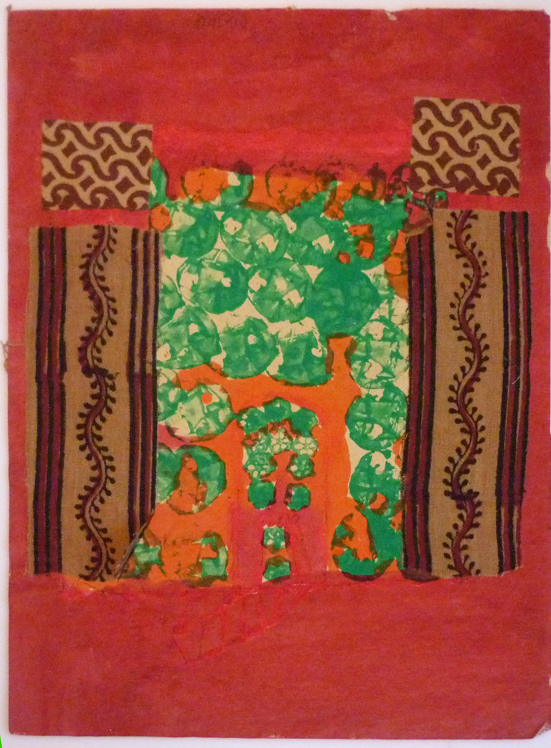

February / Madhubani painting, batik with vegetable dyes The second session took place at the Kanoria Art Centre: we had been invited to participate in the annual art festival there. Tahera, Rabia and Farzana were in the madhubani workshop, conducted by Shatrughan Thakur. The selection was made on the basis that the three had a reasonable good hand, and were more fluent at drawing than the others. The idea was to use the madhubani tradition as a teaching aid, to help them arrange elements spatially, on a flat surface – the girls’ level of perception and expression of the physical world corresponded with the strong decorative sensibility of folk and tribal forms. They were also familiar with mehndi patterns, which appeared frequently in their drawings.

The other three, Tasleem, Shah Jehan and Rehana learnt to do batik with vegetable dyes, with Pravina Mahicha. They were inhibited about drawing, and the medium and the dyeing process were intended give them a sense of freedom and tactility. They later did a three-day madhubani workshop with Shatrughan at the Centre.

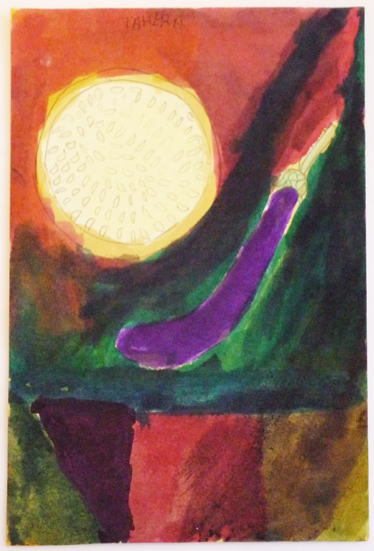

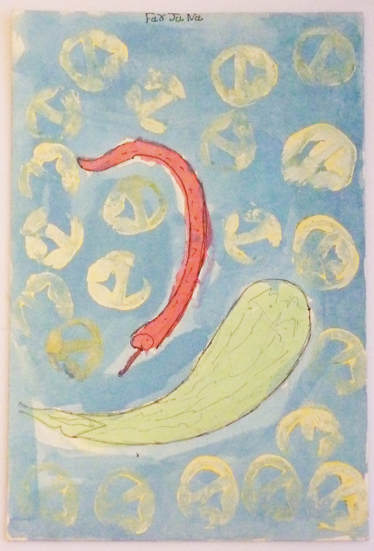

(l) Rehana Shaikh, Untitled, 2005 (r) Tahera Pathan, Untitled, 2005

(l) Rehana Shaikh, Untitled, 2005 (r) Tahera Pathan, Untitled, 2005

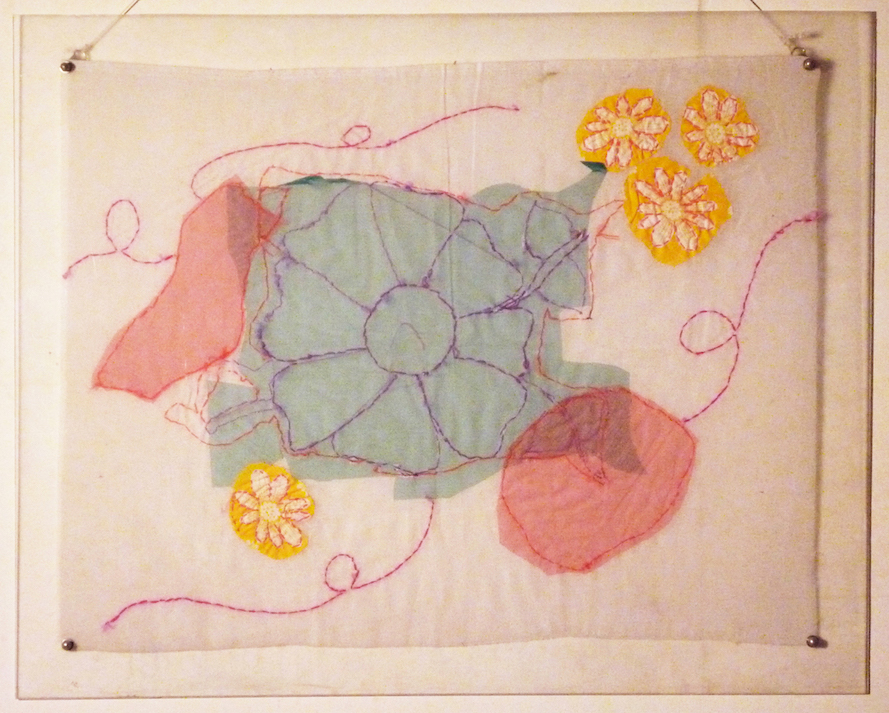

April / Fabric collage We were finally able to begin working in our own space upstairs, convenient for several reasons. We began working with fabric, and Sharifa, one of the older women, was our resource person. She could work on the haat, was expert at embroidery and basic appliqué, showed us how to transfer our cartoons on to fabric, and guided the girls whenever they needed help.

We a made a set of purely experimental pieces, with appliqué and overlapping areas of transparent fabric. It was also an exercise in colour-mixing. The work extended over two sessions, into May.

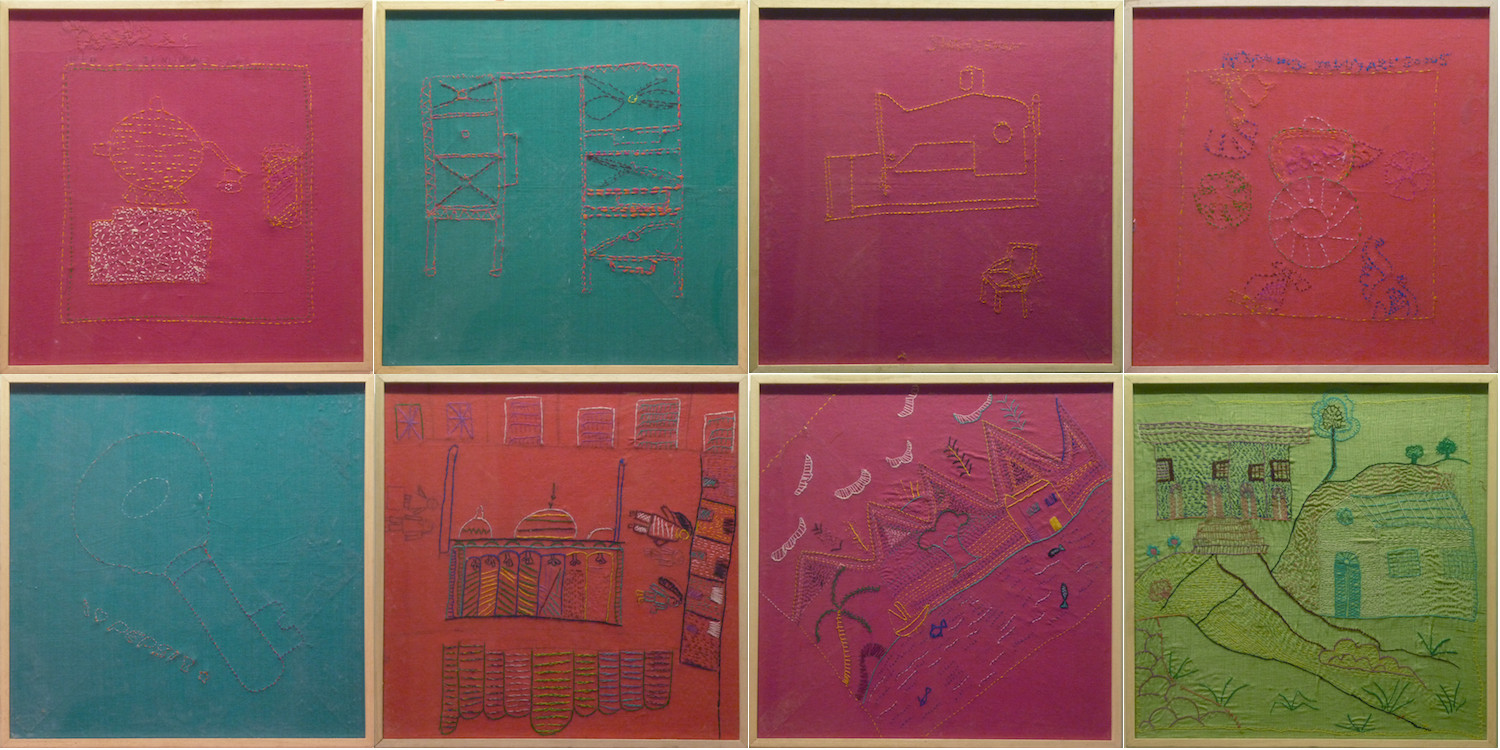

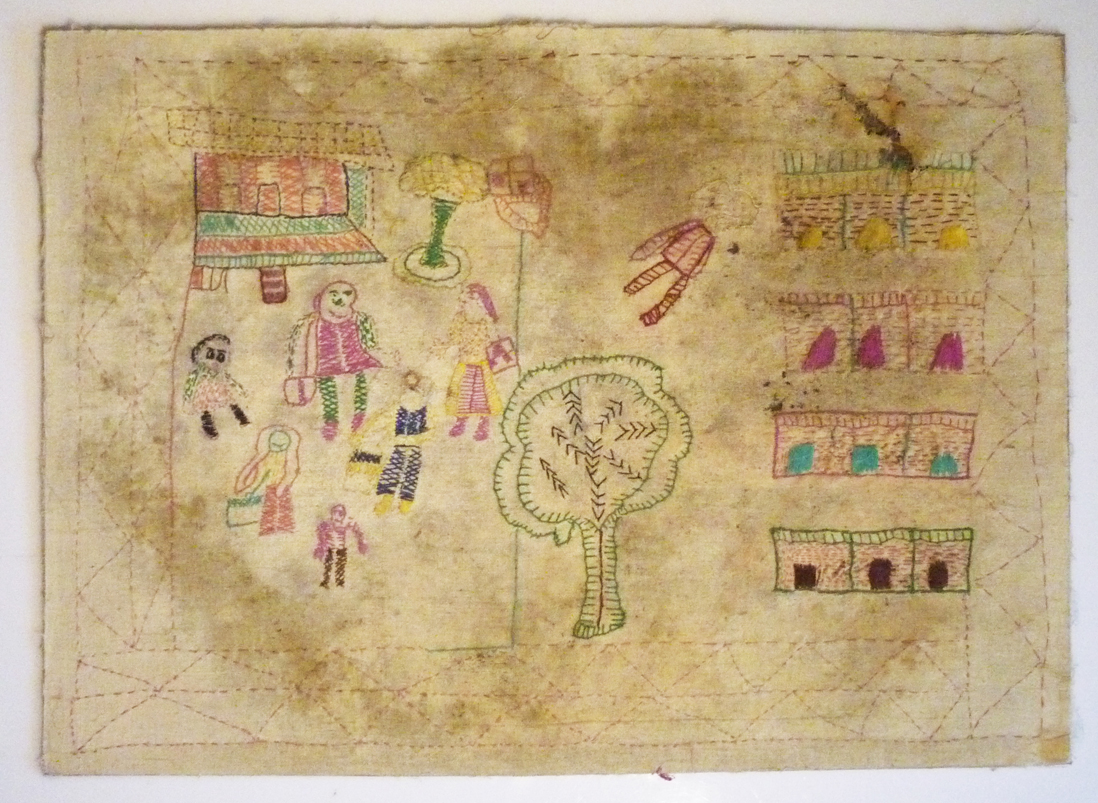

April / Fabric, embroidery We worked with Roumanie Jaitley, using the running stitch on a set of six pieces of fabric which were originally meant to be cushion covers, but they seemed significant in that the motifs were recurrent in most of their work. They are framed and presented in a manner that is in keeping with a more complex narrative.

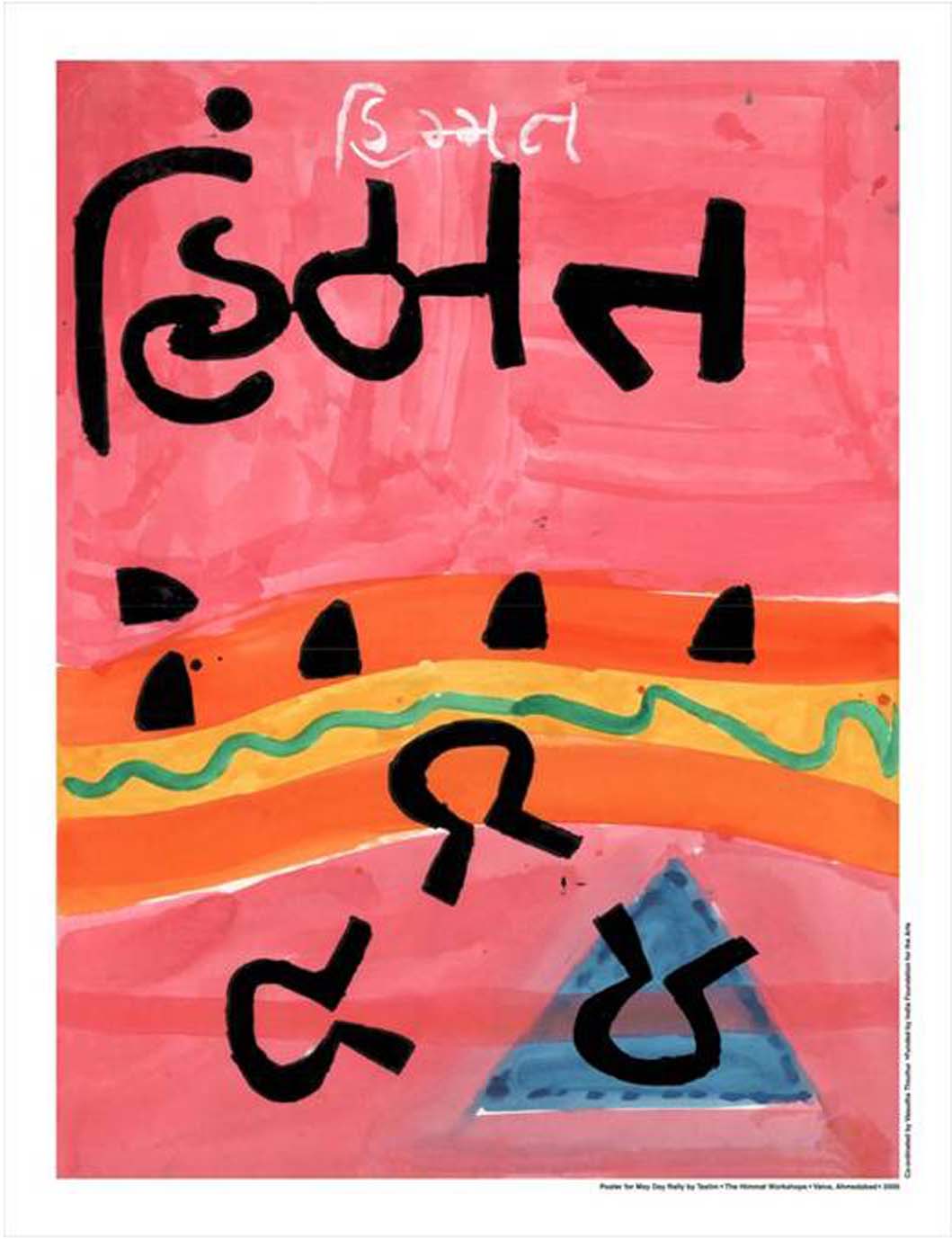

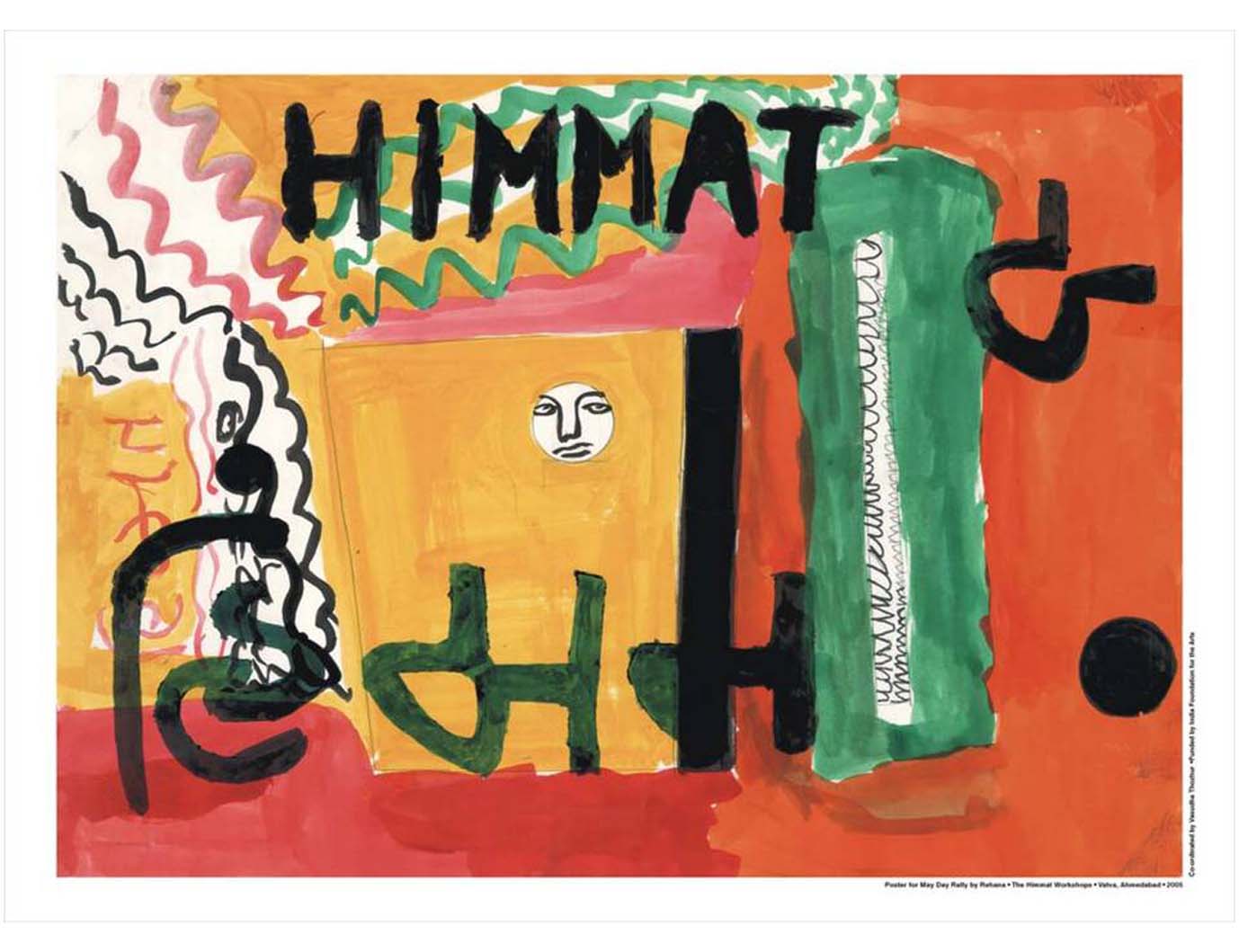

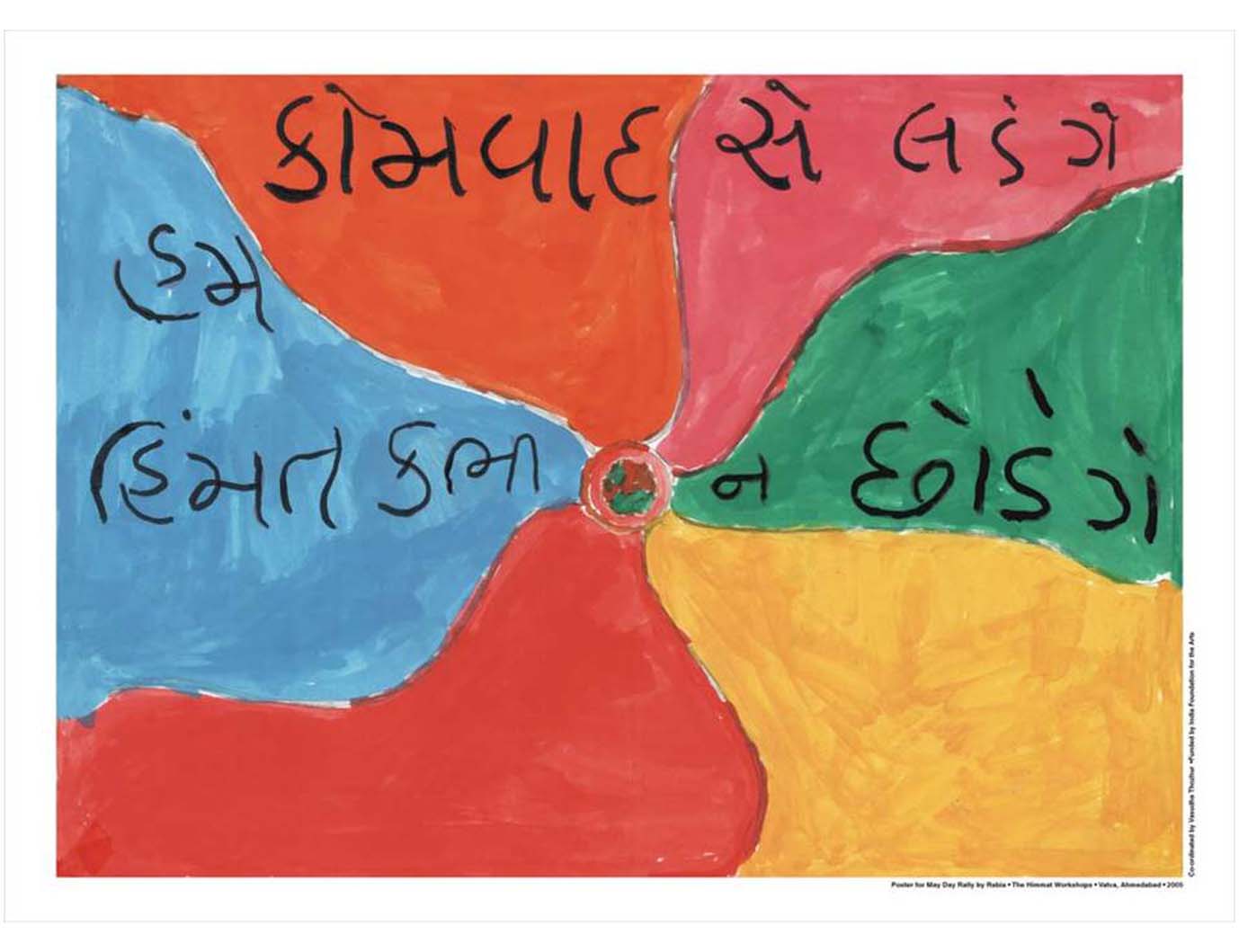

Mayday Rally Placards May 1 coincided with Himmat’s birthday – there was a Mayday rally Himmat was participating in. On the last day of April, the girls made a set of placards, very quickly, which were later taken out in procession. The slogans were composed by Monica Wahi.

Taslim Qureshi, Untitled, 2005

Taslim Qureshi, Untitled, 2005

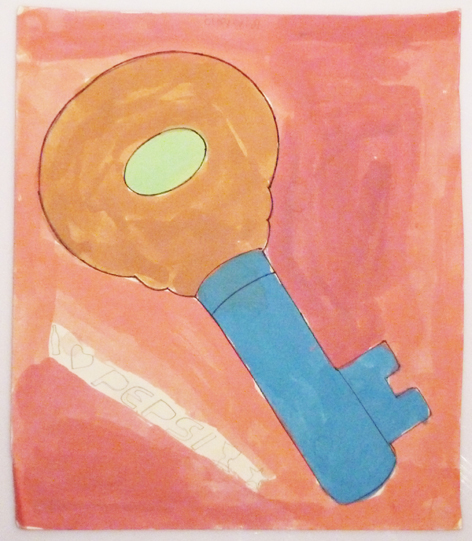

Shah Jehan Shaikh, Untitled, 2005

Shah Jehan Shaikh, Untitled, 2005  Rehana Shaikh, Untitled, 2005

Rehana Shaikh, Untitled, 2005  Rabia Shaikh, Untitled, 2005

Rabia Shaikh, Untitled, 2005

June / Collaborative Painting The girls painted six small canvases, 1′ by 1′, one each. In October 2006, at a residency in Khoj, New Delhi, I added seven more of my own. This was meant to be a partial fundraiser for some of the framing that needed to be done for a trial exhibit in Delhi. The work was acquired by the Vadehra Gallery, and the proceeds distributed in a manner that works towards sustainability for all concerned.

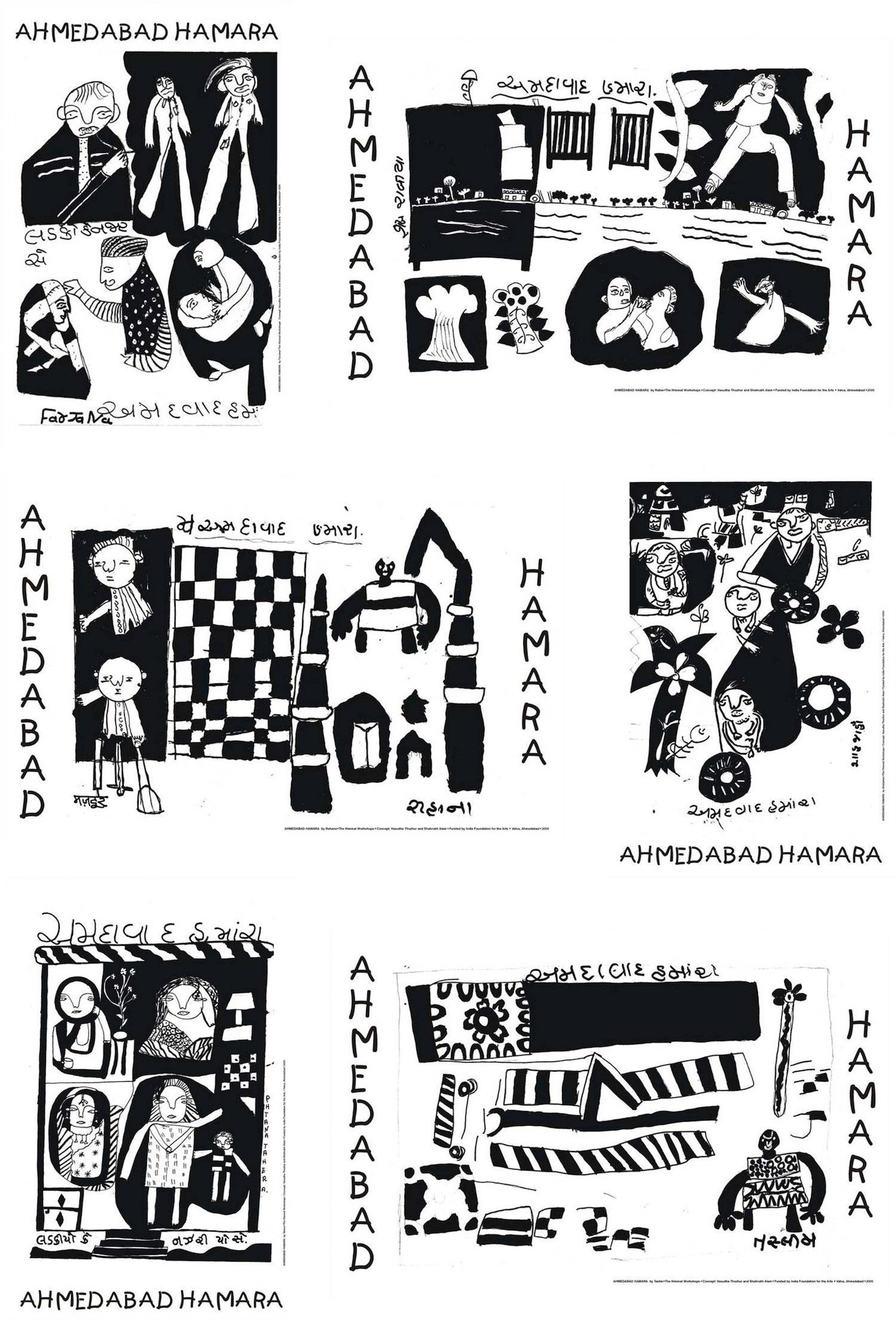

June-July / Ahmedabad Hamara Shahrukh Alam, a lawyer associated with Action Aid was involved with a stay order vis-a-vis the demolition of bastis in an area called Mahakali, after a mandir that is built there. We asked her if she would conduct a few sessions that would work towards rights-based empowerment. Between June and July Shahrukh did six sessions with the girls. To begin with, she decided to do a film based module whereby the girls would learn to critique what they were exposed to in terms of advertising/media and the visual language in general.

A VCD was hired, and set up in the centre. Shahrukh screened different kinds of films – documentary, Bollywood, activist – there were discussions afterwards which were very lively. The discussions culminated in a set of collages, using old newspapers, magazines, around some specific themes – Ahmedabad Hamara (a topic the girls chose) from different perspectives – male, female, rich, poor. The collages were in the form of collections of photographs relating to these issues.

August / Silk-screen printing Tracings were made from the photo montages, the choice of images was left to the girls. This process simplified the forms. They were rearranged as compositions pertaining to the above topics; the girls were guided as to how to convert the completed drawing into a graphic black and white format suitable for silk screen reproduction. We were thinking in terms of an affordable graphic medium, requiring hand skills the girls could learn.

The drawings were scanned and printed on transparent film. The image could then be transferred onto the screen through a simple photographic process.

Shatrughan Thakur offered to help us, as a resource person. Sharmila Sagara gave us permission to print at the studios at Kanoria Centre for the Arts. In September, we made six editions of 12 prints each. The posters are also about building a relationship with the city, and affirming a presence within it.

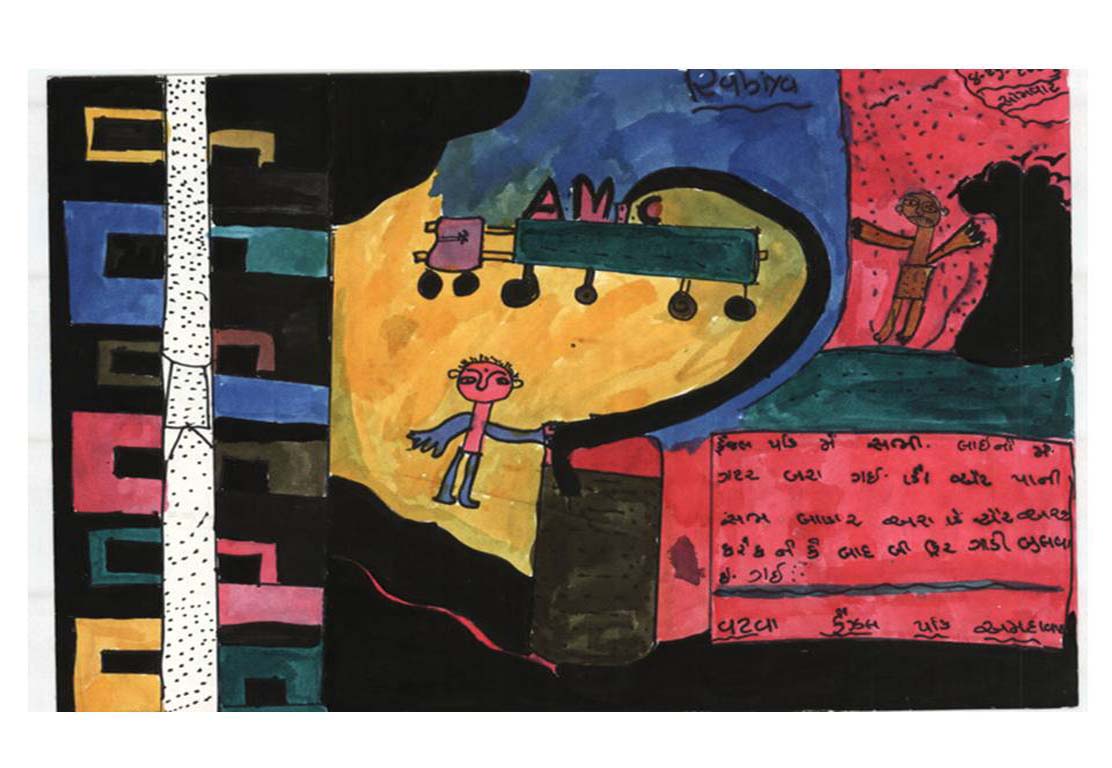

September / Pen and ink drawings We had developed a methodology – our resource person Shahana discussed issues with the girls during the literacy sessions, and helped them make small sketches in their notebooks. They also wrote about what they had drawn. They had developed a good understanding with her, based on shared experiences during and after the riots. One of the themes that they had worked on was the floods during the monsoons in 2005, they had drawn and written about the absence of a drainage system and the resulting difficulties.

During the screen printing session we made larger pen and ink drawings using the sketches as the basis.

September / Paintings by Tahera and Farzana Tahera and Farzana completed their printing session before the others, and one of the young artists working at the Kanoria Centre, Shanta Rakshit, took them out for some sketching and painting. Tahera made a painting of the façade of the School of Architecture, and Farzana of the sculpture on the grounds of the campus.

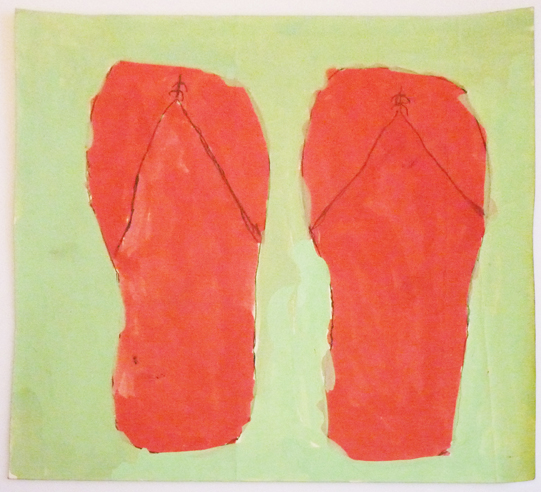

Farzana Shaikh, Untitled, 2005

Farzana Shaikh, Untitled, 2005

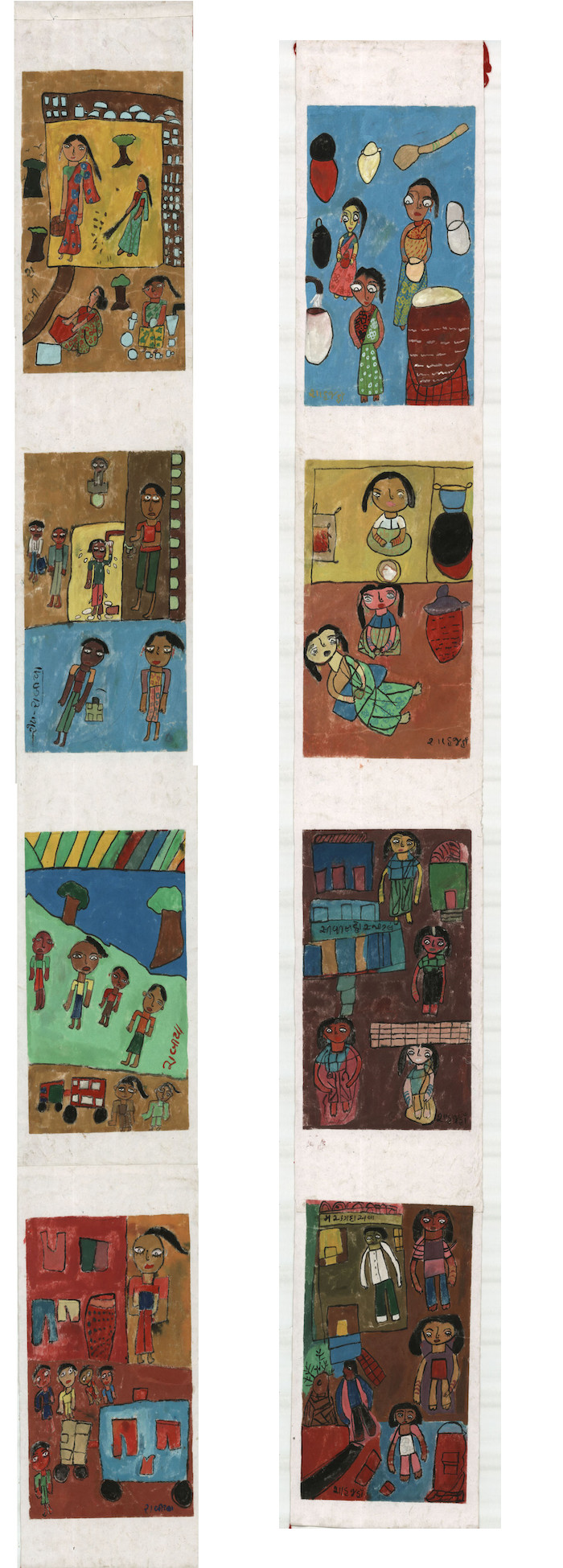

October / Four ‘Pats’ Santa Rakshit conducted a module with the girls: the theme chosen was ‘Mother’. They made scrolls in the tradition of Bengal ‘pats’, and the narrative speaks of daily domestic routines, difficulties, struggle – also related to the aftermath of the riots of 2002 – looking for work, lining up outside the government office where the death certificates were issued, visiting injured relatives at the hospital.

October / 15 Paintings Monica Wahi conducted a session with the girls – based on three questions that they were to ask each other in private. They made rough sketches based on what they told each other, about their families, details of their daily lives; and those who died during the carnage are included in the family portraits. Apart from other things, this was an exercise in bonding; the session would help build closer relationships amongst the group.

Fifteen paintings were made on the basis of these drawings, in enamel paints (industrial) on canvas.

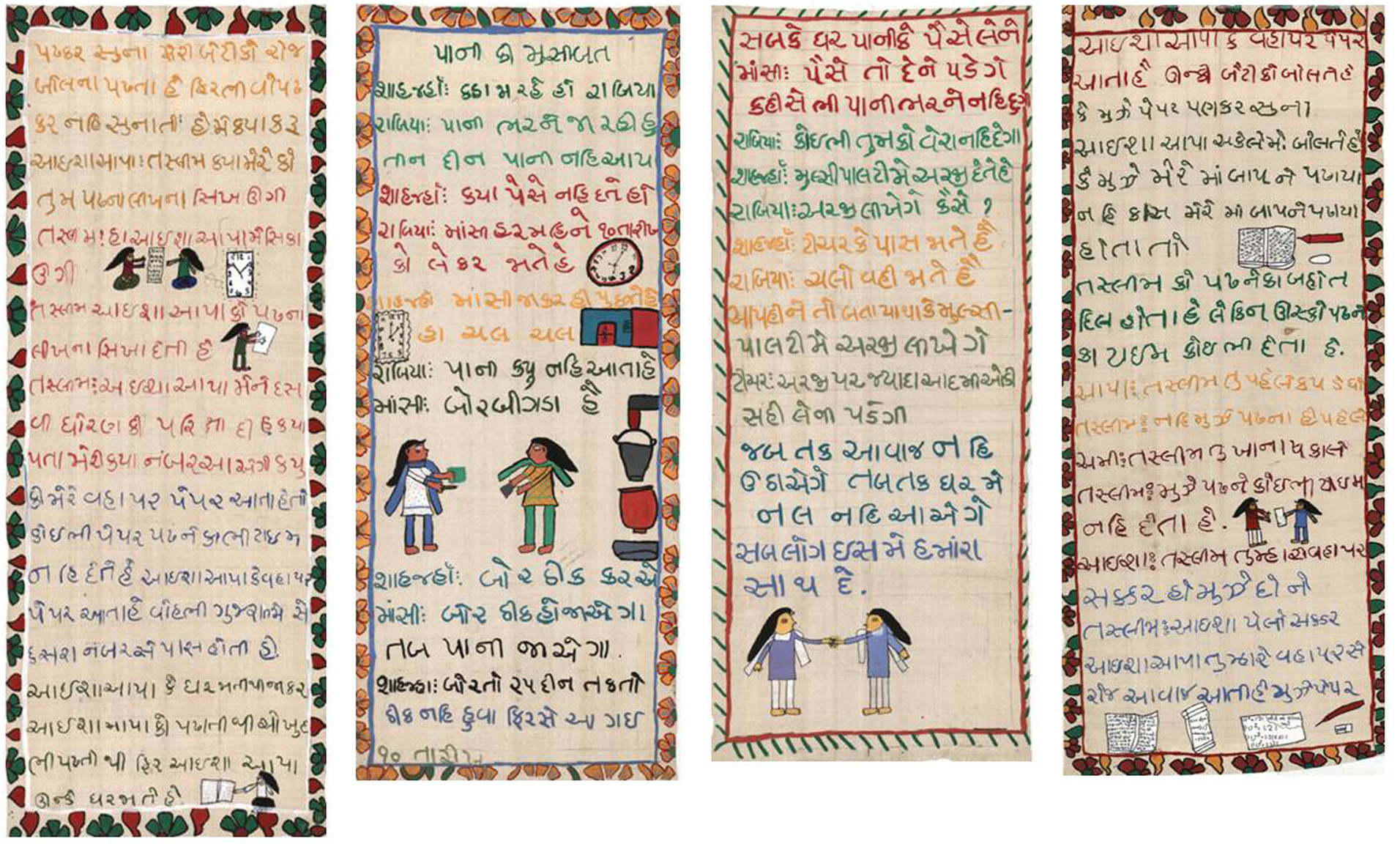

November 2005 – March 2006 / The Drishti Fellowship The girls won the Mirror Amdavad Fellowship (for two months, to be followed by an exhibit/ performance) after intensive interview sessions with Drishti. The concept combined painting with performance in the form of four long painted scrolls on canvas, the script of two plays written on four khadi scrolls. The plays developed from discussions within the group. Two broad themes emerged, one around the non-availability of water, the other around education. Prem, from Soumya Joshi’s troupe, trained the girls for a few days. The plays were performed at the Centre. The scrolls were toured locally, in the neighbouring bastis, as a narrative piece, and also taken out on a rally. When mounted in an exhibition space, they take the form of an installation.

April 2006 / Video Filming This module was conducted with the help of Johanna Hoyne, an art student from the Australian National University. The girls learnt how to handle a video camera, and created footage related to whatever was current in their lives – the plays that they had produced, learning to ride a bicycle, visiting the dargah, interviewing each other about the project that they had been a part of. Six films have so far been edited from this footage, most of them of a documentary nature. The editing was done during a residency at Khoj Artists’ Workshops in Delhi. The longest film, ‘Cutting Chai’, is about visiting their homes in Faizal Park.

May–June / Embroidery on Fabric This being the last formal session in terms of the sequential development of the project, the idea was to be able to translate the drawings, paintings, and other forms of visual output into motifs and narratives on fabric. They could then be sewn into cushion covers, curtains, wall hangings: functional household and other accessories that could be sold to generate an income. With Santa Rakshit the girls learnt to work with the traditional kantha form of embroidery. An important aspect of this module is the originality of the motifs and other elements used, evolving as they did entirely from the girls’ work – thinking about the market does not necessarily preclude creative expression arising from the experiences of a community. They can in fact enter the commercial stream as personal expressions which have the added component of sustainability in the financial sense of the word, while still remaining an authentic record of an evolving cultural consciousness. We framed the cushion covers because they were rich in imagery and narrative.

October / Quilts With the samplers that the girls had made while learning different stitches, and with pieces of hand block printed, vegetable dyed fabric, we created two quilts that are installed along with the other exhibits, guided by Neha and Deepa Sharma.

Farzana Shaikh, Still life, 2005

Farzana Shaikh, Still life, 2005

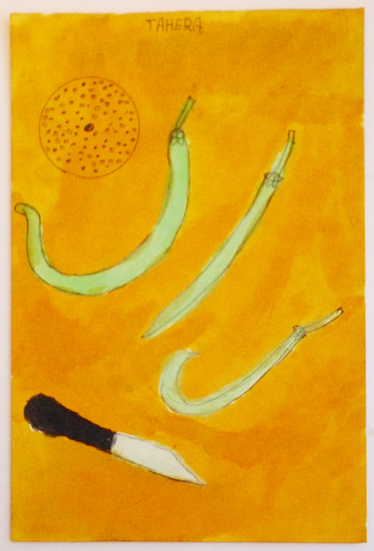

Tahera Pathan, Still life, 2005

Tahera Pathan, Still life, 2005

Taslima Qureshi, Untitled, 2005

Taslima Qureshi, Untitled, 2005

Farzana Shaikh, Untitled, 2005

Farzana Shaikh, Untitled, 2005

Portfolio of participants, 2005-06

Portfolio of participants, 2005-06

How did the project impact your work?

If I have to put it in a nutshell:

It exploded the frame within which art functions, and re-situated it in the reality outside the frame.

It re-affirmed my faith in art as I experienced it outside the frame.

The frame itself began to seem less constricting, as it was not merely a fragment of the infinitude.

It gave me immense political clarity, which I was able to apply to everyday life and work.

Art as I now see it is a flow which cannot be contained, and therefore is the source of life.

It works against confinement and abrupt terminations – and is in the truest sense anti-war and anti-violence.

To be able to see it in this light would be to take the next step towards a more evolved state.

Painting acts out this belief.

Painting as a material presence is a record of the process which accompanies it.

Could you tell us more about the afterlife of Himmat; the young artists’ personal and professional lives since the workshops?

All the girls in the group are now married with families. Rabia and Shah Jehan continue to work with other members of their families for the wholesale garment market. Tasleem has moved back to Naroda Patia. The girls periodically paint the walls of the centre, and also work with volunteers who regularly visit Himmat. Tahera attends community workshops regularly, as one of the Himmat representatives, as she is vocal, articulate and has strong views on most things.

More on the conception of the Himmat Workshops:

(Excerpts from a 2007 interview provided by the artist)

The project was most active on that front between 2002 and 2007 as it involved fieldwork and direct interaction with the community. Himmat, the collective that I worked with, had already been set up, and certain essential questions such as livelihood had already been addressed. One merely facilitated the natural process of rehabilitation in the way that one knew best, as an artist, through creativity. My contribution was to set up a small art center. A range of activities were generated, all of them linked to the existing framework, and to events of significance to the community.

The idea was not to impose, but to weave into the fabric of everyday life, vocabularies and ways of expression that were not dependant on verbal literacy – expression signifies an assertive presence in the world, and is essential for survival.

The power of the image, and the power of art are inextricably intertwined with expression. But it is ironic that art that characterizes the mainstream has been robbed of that power, while art that exists outside of it prevails – in advertising, entertainment and in politics. People’s lives are shaped by the latter, and not by so-called works of art. What went wrong? One of the aims of the project was to investigate this paradox.

2002 in Gujarat was a turning point, personally and politically. There was an overlap in terms of a destruction of belief, a crisis of faith – in humanity and in art. Art cannot be anything but political, in that it is imbued with one’s world-view. Everything hinges upon this – the choice of subject-matter, the manner in which it is expressed and shown, the range of art-related activity that one is engaged in, the life one chooses to live. Whether it is lived in the studio or out of it does not impact its authenticity – or lack of it. After a phase of fieldwork, I did several talks and presentations in different cities and institutions – which were as much a part of the ‘project-as-an-artwork’ as the paintings, prints, posters or anything else. It was and still is important to create different kinds of platforms to communicate what occurred, and to present it through changing perspectives as we travel further and further away from the immediacy of the experience. Somehow it never seems to lose its relevance.

The work has therefore entered a different phase, as you can see. I no longer feel any guilt in working from my studio, its what I am best at, and the project has restored to me the faith that I had lost. I think that the processes that lead to art-making are situated in the real world, and involve decisions that impact the social and political spheres. Art gives a form to this process, makes it visible – and in that it is self-fulfilling, or what one would call art for art’s sake – a much maligned term. At that point one has to suspend other concerns and concentrate on language and expression. Otherwise what one creates is neither community nor art.

Despite varying degrees of emphases, all art is public, in the broadest sense, and subjectivity is the prism that throws light on a worldview which is in continuous formation. The studio embodies this position. It is at the threshold to a world whose dimensions are informed by the senses, through which we perceive and interact with what is outside of us. An active use of the streams of language that radiate from this space give rise to different modes of engagement, in quality and quantity, and is a more complex way of envisioning the continuities of our shared space. Within the limitations of each aspect of this space, there is room for an active inter-subjectivity in relationship to those who we work with or address. There are qualitative differences, but space is always public if we are conscious of the communicative potential of our work.

(Excerpt from a 2016 paper by the artist)

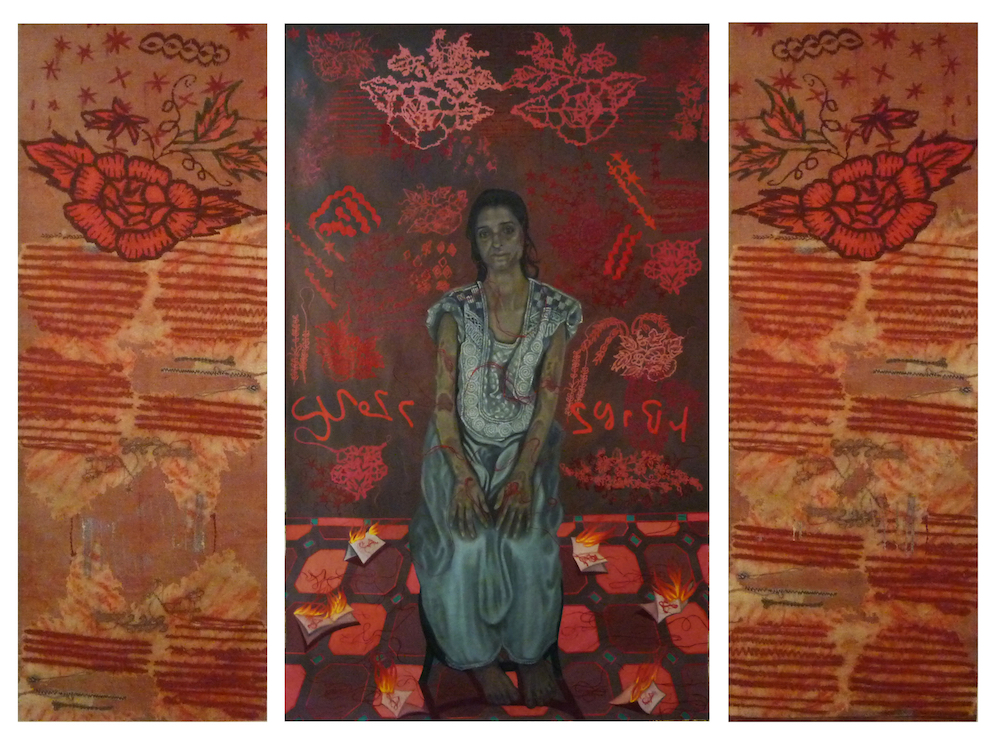

Vasudha Thozhur, ‘Portrait of Shah Jehan’, 2008-11 / Read more here

See here for details about the Himmat group’s exhibitions and grant awards (pdf).

Watch Rakesh Sharma’s documentary Final Solution here, or an excerpt here on the Indian Cultural Forum (ICF) site.

Click here to read ICF’s 2016 interview about the Gujarat pogrom with human rights activist Teesta Setalvad.

You can also read a report about the pogrom by Human Rights Watch, ‘We Have No Orders to Save You’, here.