Goa conjures several impressions in one’s mind. The name usually smells of a riff on touristy destinations; but it can have other resonances: the bombing of the Indian Air Forces that took away Goa’s sovereignty in 1961, the poems of Manohar Shetty, and also, the increasing menace of mining. In a new-liberal economy, mining has only shown its ugly face more shamelessly. Orijit Sen, the graphic novelist and designer, offered a two-week course on representing mining through the form of comics.

Called ‘Digging Deeper — Creating short comics about the story of mining in Goa’, the course was open to the students of the University of Goa, as well as to the general public. Prior experience in drawing comics was not required for this course, and these comics form valuable archives into the perception of mining for these students.

One of the recurring motifs in these comics is the loss of an idyllic past as a result of mining. This past is usually narrated through stories by another character, or by a third-person narrator. Ashish A. Naik’s ‘Beauty with Destruction’, for instance, begins with the convention of the fairy tale: ‘Once upon a time, there was a place so rich in beauty that a God called Pisu decided to go there and make a home’. The use of a mythical past is a way in which Naik shifts the much nearer, historical past of pre-mining Goa further back. The implication is that the landscape of Goa has changed irrevocably. There is no way one can restore the disappearing hills, and so the only recourse one has is that of storytelling: the story of a mythical Goa, the story of Pissuriem. In Pradnya Gaonkar’s ‘Village with Destruction’ too, the child narrator is bewildered when her hopes of seeing ‘natural beauty’ are dashed on her first visit to Goa. Then, it is her grandfather who tells her the story of the village before 1990, the year when mining started. The visual is of a rising sun behind the hills, and an abundance of fishes, rivers and trees in the valley. Gaonkar’s depiction is more historically grounded, but it also looks toward the future. It proceeds with younger villagers organising themselves, and ends with a clarion call to action: ‘Let’s protest against mining’.

In all the representations of Goa in the pre-mining period, the community is foregrounded. They are seen working together, not just with each other, but also with the resources around them. Anthropomorphism is always balanced with representations of bountiful nature. This balance is completely ruined in representations of mining: there are no trees, no rivers, no birds, but a mountain of dust with a handful of men. Journalist and thespian, Hartman De Souza, in his book, Eat Dust, too raises pertinent questions about environmental destruction:

The idea that a hill just disappeared left me fuzzy-headed. How does one come to terms with the deliberate destruction, in peacetime, of agricultural practices and the everyday life of people whose only crime is that they live here? Or the wasteful hacking of trees, the seismic upheaval of mud, the conscienceless blasting of aquifers? All of the forest’s original inhabitants — the fish, otter, crabs, spiders, beetles, butterflies, moths, lizards, frogs, birds, hares, porcupines, deer, wild cats, wild boars, leopards, bison and even tigers turned refugees. Keeping aside the problems faced by an entire community whose way of life is altered, there is also the individual who faces a tremendous psychological crisis.

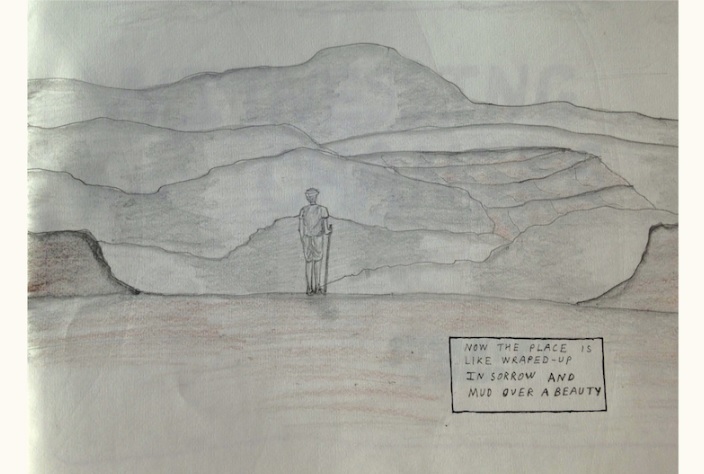

The tragedy of an individual who cannot bear to see the sight of a changing landscape is best represented in Susanket Sawant’s ‘Witnessing Changes’. The narration is by a farmer who has experienced these changes first-hand. Unlike the other comics, the pre-mining past is not narrated by another older figure but witnessed in the first person. Sawant uses grey pencil sketches in the first half to depict the idyllic life, but the shift comes with the use of red which offers a stark contrast to the sombre grey. The last panel is a stunning depiction of an individual completely alienated from his surrounding: the solitary farmer is seen facing the entire landmass of hills of dust. He is, quite literally, eating dust.

– Souradeep Roy